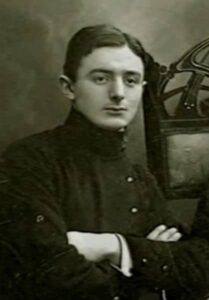

Like many other great Soviet filmmakers of the Russian avant-garde, David Abelevich Kaufman – better known by his revolutionary pseudonym Dziga Vertov – came from a largely scientific background, having likely been first introduced to film as a tool in one of his science classes at university. Given this fact, it is perhaps understandable that all of his works display an uncompromising dedication to capturing reality and the physical world.

Dziga Vertov’s Early Life and Education

Vertov was born in Bialystok in what is now Poland on 15 January 1896. His parents were librarians before becoming successful bookstore owners, starting in 1893. The couple wed one year later in 1894 and had three sons besides Vertov: Semyon – who died in infancy – as well as Boris and Mikhail.

In a remarkable turn of events, all three brothers became famous for their contributions to cinema: Boris became a successful cinematographer in Europe and America, while Mikhail collaborated with Vertov and directed several films of his own.

Vertov’s parents made sure that they received a liberal, Russified education. Vertov was enrolled at the Bialystok Modern School from August 1905 through June 1914. There he met Mikhail Koltsov, who later became a journalist and figured prominently in Vertov’s career.

Both friends Russified their names. Vertov’s original first name was Denis while Koltsov’s full name had been Moisey Haimovich Fridlyand. Both names would have immediately identified them as Jewish. The Russification of Jewish names was common and likely fueled by the overwhelmingly antisemitic atmosphere prevalent in Russia at the time.

Vertov also attended classes at the local conservatory during this period and developed an early interest in music and poetry. He had his first experience with photography around this time when his aunt gifted the family a still camera.

Vertov later moved to Saint Petersburg and enrolled at the Bekhterev Psychoneurological Institute in the fall of 1914. The institute was relatively new and a popular destination for young Jewish intellectuals due to its lax observance of state-imposed Jewish student quotas.

He was joined there by his former classmate Koltsov and met many soon-to-be members of the Soviet intelligentsia while studying there.

Vertov began experimenting with scientific film at the Bekhterev Institute, using timelapses to chart the growth of plants, while also working on creative and experimental “sound collages.” However, World War One effectively ended his studies.

Most of the Kaufman family was forced to evacuate Bialystok in 1915 when German forces overran the city. The Kaufmans moved to what is today St. Petersburg and then Moscow before resettling in Bialystok at the end of the war.

In 1916 Vertov joined the Russian army as a musician at a military academy near Kharkiv, Ukraine. He remained at the academy until the February Revolution of 1917 when he left the army and traveled to Moscow. He spent much of the following year mingling with the avant-garde of the Moscow art scene at various cafes and public poetry readings.

The “Spinning Top” and His First Films

Vertov met the young cameraman and cinematographer Aleksandr Lemberg, a future collaborator, sometime in the fall of 1917. Lemberg introduced him to the world of creative film.

Around this time, Vertov adopted the revolutionary pseudonym “Dziga Vertov,” which translates loosely from Ukrainian as “spinning top.” The name may have referred to many things, including the rotating wheels in video and audio apparatuses at the time, to the revolution itself, to his dynamic, motion-oriented cinematographic style, as well as possibly to Vertov’s concealed Jewish heritage, of which the dreidel, a spinning top, is a major piece of cultural heritage.

In 1918, Koltsov was appointed head of the newsreel division of the All-Russian Cinema Committee of the People’s Commissariat of Enlightenment. One of his first acts as head of the division was to hire Vertov as his personal secretary.

By the end of 1918, Vertov was the chief administrator of the Kinonedelia, which translates as “Cine-week,” newsreel series. Vertov’s unique style of documentary filmmaking can be seen even in these early works: whereas most contemporary newsreels relied on static shots with intertitles to relate single events, Kinonedelia uses dynamic shots and editing to convey arguments about the state of life in Russia. An example cited by Jeremy Hicks in Dziga Vertoв: Defining Documentary Film uses shots of ships sailing down rivers, sunken barges, and supplies waiting on piers to show how badly communications were disrupted by the Russian Civil War.

This style of editing – called “montage” after the French word for assembly – was pioneered in fiction films by Russian film theorist Lev Kuleshov and later perfected by the famous directors Vsevolod Pudovkin and Sergei Eisenstein. The idea at the heart of montage was that by juxtaposing two contrasting scenes the director could force the audience to make a connection between them and form an entirely new meaning. In the case of Kinonedelia newsreel cited above, all three shots – river travel, sunken barges, supplies waiting on the pier – have their own meaning. However, when edited together, they convey a new idea about the economic state of Russia. Although montage theory was already well known by the time Vertov created his first newsreel, it had never been applied to the documentary genre before.

Kinonedelia was discontinued the following year after forty-three issues. Vertov was subsequently transferred to a project called “October Revolution,” which was a mobile screening and filming effort that traveled by train to spread the word about the new government and its policy goals. In this, Vertov was joined by several notable filmmakers including Lev Kuleshov and Vladimir Gardin. He met his first wife, pianist Olga Toom, while working on the project, although their marriage lasted only a few short years.

In between filming trips, Vertov worked on his first major film: the now-lost 1919 Battle of Tsaritsyn, about a Russian Civil War battle in which Stalin played a major role commanding Bolshevik forces. The only member of the Moscow Cinema Committee editing staff willing to make the unusual edits that Vertov wanted was Elizaveta Svilova, the woman who became his second wife and longtime colleague after he and Olga separated in 1923.

Vertov’s Films in Revolutionary Context

Vertov’s entry into the world of filmmaking occurred at an important time in Soviet film history. The 1920s were a period of great artistic and social experimentation in the nascent Soviet Union. Russian Futurism – an offshoot of the broader, pan-European Futurist movement that celebrated modernity, technology, motion, youth, and revolution – had already grown into an immensely influential faction within the Russian avant-garde.

In his influential 1912 Futurist manifesto A Slap in the Face of Public Taste, Vladimir Mayakovsky famously called for a new, scientific mode of artistic production:

Cinema for Vertov was the visual art of the revolution. He believed that it could provide the sort of scientific mode of expression that the Futurists desired.

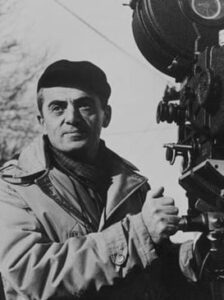

In 1922, Vertov founded the Kinoki group with his brother Mikhail and editor Elizaveta Svilova to further this Futurist vision. “Kinoki” was an invented term that they chose to replace the longer and more formal “kinematograph,” the Russian word for “cinematographer.” It translates as “Cine-eyes.”

The Kinochki published their manifesto, WE: Variant of a Manifesto in August of that year. In it, they claim to be seeking an entirely new form of film, one that would draw from new material, exist in four dimensions, and would be “cleansed” of

Vertov’s Futurism in Cinematic Practice

By 1922, Vertov was a high ranking leader within the newsreel department of the State Committee for Cinematography (Goskino). In that same year, he began work on a weekly film journal called Kinopravda, a name that translates to “Cine-Truth.”

Vertov hired his brother Mikhail to work on these after his discharge from the army. Vertov also met many leading members of the Russian avant-garde through his work, including the famous constructivist artists Aleksey Gan and Aleksandr Rodchenko.

Kinopravda grew into an extended experiment as Vertov pushed the boundaries of newsreel and documentary cinema, incorporating new techniques like animations and moving intertitles – some of them designed by Rodchenko himself – to weave a tapestry of the revolution.

Twenty-three issues of Kinopravda were produced between June 1922 and March 1925 with each one covering a particular aspect of life in the USSR, from the death of Lenin to the collectivization of agriculture.

To help with this project, Vertov created a USSR-wide network of film correspondents. The network provided him with footage from across the country and worked to increase the popularity of cinema. Some of its members even went on to become directors themselves, most notably the Soviet documentary filmmaker Ilya Kopalin.

Kinopravda culminated in the 1924 feature-length film Kino Eye, a series of five separate newsreels about the activities of a Moscow-based Young Pioneers troop. Kino Eye met with much critical acclaim at the 1925 International Exposition of Modern Decorative and Industrial Arts in Paris but failed to earn any awards. However, its relative success earned Vertov two commissions, one from the Moscow City Soviet for Stride, Soviet! and one from the State Office for Imports and Exports (Gostorg) for One Sixth Part of the World.

Both films proved immensely controversial.

Stride, Soviet! was commissioned in advance of the Moscow Soviet election year to promote the accomplishments of elected Soviet officials, but the actual film never mentioned the officials themselves.

One Sixth Part of the World was commissioned to promote Soviet exports abroad but was never used for international advertising because of its savagely anti-capitalist rhetoric and difficult narrative. It was also judged to have had excessively high production costs.

Vertov was subsequently fired from Goskino in 1927 and spent most of the next year writing unused film scripts before the All-Ukrainian Photo-Film Directorate (VUFKU) hired him.

His first film at the new studio – a characteristically stylized and novel documentary called The Eleventh Year, detailed the achievements reached by the USSR in its first ten years. It was released in 1928 and met with overall mild reactions. However, his next releases would be his most memorable.

Above: One Sixth Part of the World, in full, for free, on YouTube.

Man with a Movie Camera: Vertov’s Masterpiece

Man with a Movie Camera used footage that Vertov had amassed over the course of three years and it went

through at least two versions. It was long a project in flux and another reason for his firing from Goskino was his refusal to submit a script for the film.

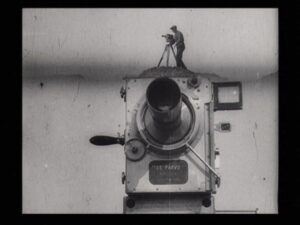

Finally released in 1929, Man with a Movie Camera stands out as one of Vertov’s most complex and difficult films. It follows Vertov’s brother and cameraman Mikhail as he records scenes of daily life in the modern Soviet cities of Kharkiv, Kiev, and Odessa. A train pulls into a station; athletes practice swimming and pole vaulting for a small crowd; a young woman packages cigarettes in a factory; two men play chess in a workers’ club. There are no real characters apart from Mikhail, and even he is later revealed to be of secondary importance to the camera itself, which leaps up and operates of its own accord through a series of stop motion animations.

Man with a Movie Camera functions as a graphic illustration of the Kinoki manifesto. Instead of relying on plot or conflict for structure, Vertov uses rhythm and mechanical motion – captured in the workings of machines like coal elevators and trams – to carry the narrative to its conclusion.

The film feels like a celebration of the Futurist ideals of modernity and dynamism and an ode to the Soviet Union’s victory over industrial backwardness. Vertov’s inventive editing even makes it look like the mechanical precision of the factory has seeped into the lives of ordinary citizens. Clips of the young woman packaging cigarettes are sped up to superhuman speeds, while the chess board automatically resets itself by rewinding the scene.

Man with a Movie Camera was largely derided by critics and misunderstood by the public at the time. It was also his last film produced with his brother and cameraman Mikhail. Tensions between the two had grown during production of The Eleventh Year and the two abruptly ended their collaboration after Man with a Movie Camera.

The movie proved to be simply ahead of its time, however. In the following decades, its reputation grew internationally. Although it is now regarded as one of the most cinematically daring and innovative documentaries of all time, its initial release must have been a great disappoint for Vertov.

Unlike at home, his unusual style was remarkably well received abroad, where his films were widely circulated and written about in various film journals.

Above: Man with a Movie Camera, in full, for free, on YouTube.

Vertov’s “Sound Documentary” and Three Songs of Lenin

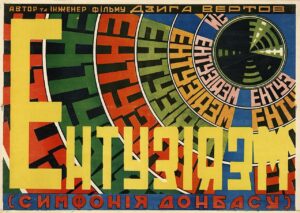

Enthusiasm: Symphony of the Donbass was released in 1931. It is another highly inventive piece, mixing industrial sounds to an orchestral soundtrack. Its release was long delayed as state committees debated whether it was fit for release. When it finally was released, audiences recoiled, confused by the fast-paced, largely voiceless film. It was pulled from theaters soon after.

His films, Enthusiasm in particular, received much more critical acclaim in the West than they had in Russia. Writing in Russia’s People of Empire, scholar John Mackay cites a particular screening of Enthusiasm where the famed silent film actor Charlie Chaplin himself praised Enthusiasm as “one of the most exhilarating symphonies [he had] ever heard.”

His Western admirers also included the English science fiction writer H.G. Wells. He was not without his foreign detractors, however. John Grierson, a pioneering English documentary filmmaker, reportedly detested Man with a Movie Camera and derided it as a “snapshot album.” Regardless, Vertov returned to the USSR in 1932 refreshed, making a personal note of Chaplin’s praises in his journal.

Vertov next left the Ukrainian VUFKU studio and joined the German-Russian international film studio Mezhrabpomfilm where, in 1934, he produced the most popular film of his career: Three Songs of Lenin. As a tribute to the former chairman of the Soviet Union, the film is a relatively standard Soviet hagiography for the 1930s. However, it is still remarkable for its blend of synchronized sound interviews and music as well as for its rich imagery from the Muslim regions of the USSR. Vertov was awarded the Order of the Red Star the following year.

Politics in the USSR were turning increasingly authoritarian, however, and in 1938 Vertov rereleased the film with a speech given by Stalin added to the conclusion and several sequences involving people that had since been deemed “enemies of the state” edited out. That same year, Vertov and his wife were gifted a new apartment in Moscow.

Above: Enthusiasum, in full, for free, on YouTube.

Final Films, Obscurity, and Death

Three Songs of Lenin would be the climax of Vertov’s celebrity status within the USSR, as the artistic climate became more and more restrictive, especially after Socialist Realism became the country’s official artistic style in 1936.

In 1937, he produced a documentary called Lullaby. He intended to decry the historical exploitation of women, but the film became so warped by political pressures that the final version barely resembled the original concept. Instead, Lullaby celebrates the place of women in Soviet society and the protections afforded to them by Stalin and the state.

Vertov’s longtime friend and patron Mikhail Koltsov was arrested in 1938 and later executed for supposedly spying for England. Although on good terms with the Stalinist regime himself, Vertov took the precaution of purging his personal library of any letters or other correspondence from Koltsov.

Vertov’s health began declining shortly after the release of Lullaby and, coupled with his commitment to Futurism – an artistic movement incompatible with Socialist Realism – he slowly faded into obscurity.

Over the next few years, he and Svilova found themselves working for various film studios, always on projects which were either never produced or never released. The one exception to this trend is his 1942 wartime documentary To You, Front about war production and life in Soviet Kazakhstan, but his final feature-length film The Oath of Youth, about the Komsomol’s contributions to the war effort, was firmly rejected by studio executives two years later in 1944 and was not released in his lifetime.

Tragically, Vertov’s parents and many of his relatives were killed by the Nazis in WWII, although their exact fate remained a mystery for many years after the war ended. While working with his brothers Mikhail and Boris to find out more about their parents’ death, Vertov submitted a number of film proposals to various film studies but was turned down repeatedly. To add insult to injury, he was denounced by several filmmakers and party officials at a meeting of the Central Documentary Film Studio in 1949 for “formalism” and producing art for art’s sake.

Vertov attempted to defend himself, but the damage was already done. Over the next few years, Vertov’s film production dwindled to nothing. His sole creative outlet towards the end of his life was poetry, which he wrote privately in his diaries. He was diagnosed with stomach cancer in 1953 and died the following year.

Above: Three Songs of Lenin, in full, for free, on YouTube.

Vertov’s Rebirth and Legacy

Vertov’s reputation rebounded in the 1960s, as Western interest in the Soviet avant-garde rose with improving relations under Khrushchev. In addition, the “Thaw” presided over by Khrushchev allowed for a renewed domestic interest in the experimental art. Vertov’s wife Svilova and friend and former correspondent Ilya Kopalin worked tirelessly to keep his work alive. A steady stream of scholarship on the late director’s writings and films soon developed in the USSR and abroad.

At the same time, a new generation of young filmmakers in Western Europe was inspired by the boldness and innovation of Vertov’s work. In 1968, French directors Jean-Luc Godard and Jean-Pierre Gorin founded the Dziga Vertov Group as a collective of politically-motivated filmmakers.

Taking inspiration from Vertov’s films and other avant-garde artists of the USSR, they produced a number of experimental and politically charged films throughout the 1960s and ‘70s, including Wind from the East (1970) and Everything’s Fine (1972).

Today, Vertov is perhaps more widely renowned than ever. In 2011, the State Film Agency of Ukraine paid to have Enthusiasm restored and re-released. In 2012, the British Film Institute named Man with a Movie Camera the 8th best film ever produced.

Vertov also remains historically controversial as his films show the USSR in an entirely positive light. The most striking example of this is Enthusiasm, which makes no mention of the terrible famines occurring in the Donbas, where it was set, during the same time period as it was shot.

Despite controversy, however, Vertov’s unique vision of cinema and pioneering innovations in sound and cinematography were decades ahead of their time and continue to be of great interest to audiences, critics, and film theorists.

Works Cited

Gillespie, Vertov. Early Soviet Cinema : Innovation, Ideology and Propaganda. Wallflower, 2000.

Hicks, Jeremy. Dziga Vertov : Defining Documentary Film. I. B. Tauris, 2007.

Mackay, John. “Dziga Vertov.” Russia’s People of Empire: Life Stories from Eurasia, 1500 to the Present, edited by Stephen M. Norris and Willard Sunderland. Indiana University Press, 2012.

Masing-Delic, Irene. From Symbolism to Socialist Realism: A Reader. Academic Studies Press, 2012.

Michelson, Annette, editor. Kino-Eye: the Writings of Dziga Vertov. University of California Press, 1984.

You Might Also Like

Films of Eldar Ryazanov, Moral Voice of the USSR

Eldar Ryazanov is remembered as one of the most influential and beloved directors in the post-Stalin Soviet era. Phrases from his movies, which is often co-wrote are still quoted by Russians as much as pieces of folk wisdom as pop culture references. He is best known for light comedies that also delivered social reflection, moral […]

Aleksei Balabanov and His Films: Cult Classics of Post-Soviet Russia

Aleksei Balabanov is one of Russia’s best known directors of the 1990s and his movies are known for capturing the essence of those turbulent years. Below is brief biography for him and several synopsis and reviews of his work, with links to watch them in the original Russian on YouTube. Balabanov’s Education and Early Work […]

You’re Next: The Cold War in American Horror Films

During the second half of the 20th century, Cold War anxiety and paranoia played out on America’s silver screens via the explosively popular horror genre. These films both reflected and shaped how Americans understood the perceived threats of a rapidly changing world. This paper examines five horror films—Them! (1954), Invasion of the Body Snatchers (1956), […]

Russian Language Horror Films

Although Russian folklore teems with fearsome spirits and creatures, horror has never taken root as a popular genre in Russian culture. In literature, the supernatural typically inflicts psychological rather than physical torment, and modern attempts at slasher horror in film have largely failed at the Russian box office. The most successful Russian horror films instead […]

The Best Soviet Films According to Soviet Citizens

In 1925, Sergei Eisenstein’s film Battleship Potemkin was released in the Soviet Union. At the time, it was regarded as one of the most important works in the history of cinema, and still often appears on lists of the world’s greatest films. However, only in 1958 did independent film ratings in the USSR appear, when […]