Starting in the late 1970s, Leningrad’s rock scene introduced a new wave of western culture to the Soviet public. For some, this wave was a dangerous cultural phenomenon that went against Party norms, but by Perestroika, Soviet rock was well established and had captivated and inspired young listeners. It also created a new sphere of normalcy outside of the official State-produced culture, in which social and political criticism found a niche.

The Roots of Soviet Rock

By the Brezhnev era, black market trade of western rock records was widespread, but prices were far too high for the average Soviet citizen. Lower quality, locally produced bootlegs recorded by enthusiasts were much more common. British and American bands, such as The Beatles, The Rolling Stones, David Bowie, The Velvet Underground, Joy Division, and Sex Pistols introduced entirely different styles of rock to Soviet audiences and created musical waves that unfurled not only in larger cities in the Western USSR but in provincial areas as well.

Leningrad became a particular hub for Soviet rock’s development. Its proximity to Finland allowed its residents to tune into Western radio stations, like BBC and Radio Svoboda Evropa. For young people, the music programs on these stations, typically aired after the news hours that attracted their parents and grandparents, offered a retreat from the USSR’s cultural isolation from the West.

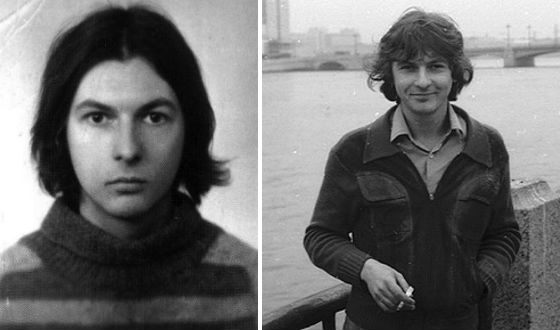

The formation of Leningrad bands like Автоматические удовлетворители (Automatic Satisfiers; here and after referred to as AU), was heavily influenced by western styles and artists and monumental in the cultural shift of Leningrad’s rock scene. AU’s frontman, Andrei Panov, was an avid punk listener and adopted punk ideology, like the “do-it-yourself” mentality and anti-conformism, not only in his music but in his daily life. Panov and his friends could often be found around Leningrad, engaged in hooliganism that verged on performance art. Several instances include when they played dead in a city park for several hours or shoveled snow naked until authorities were called. Often performing in venues off the beaten path and on shoestring budgets, Panov showed that one didn’t need expensive equipment or decadent performance spaces to draw a crowd. More importantly, he showed that one could perform independent of state support and publicly living outside of societal norms.

Panov echoed and adapted western styles with his friends in small underground venues, such as tusovki (small house parties, typically held in apartments) or even sessions in dvory (outside spaces between apartment buildings).

Above: AU plays at the Leningrad Rock Club, 1988

The Leningrad Rock Club and Official Soviet Rock

After observing the more rebellious punk styles of bands like AU and their influence on the emerging circle of Leningrad rockers, the authorities saw a need to contain the new movement under Party supervision and censorship. In 1981, the opening of the Leningrad Rock Club provided the growing underground rock scene with a performance hall and audiences with a coordinated viewing experience. Much like in a theater, audiences were expected to remain seated for rock shows’ duration. Breaking this etiquette could put audience members in danger of expulsion from the Komsomol, a college faculty, or other less official forms of denunciation.

Despite its underlying state censorship, Leningrad Rock Club became the stomping grounds for the city’s big names, including Maik Naumenko, Странные игры (Strange Games), and even former members of AU like Viktor Tsoi.

Party backing opened the possibility for rock careers with an upwards trajectory. Tickets for the club’s performances sold out quickly and attracted a wide range of young people, including Komsomol members. Fan clubs popped up as bands became more popular, and some shows became so desirable that one could turn a large profit by reselling marked-up tickets.

Auditions for club membership drew in new music groups every year, building a larger community of rockers in Leningrad. The club’s communal nature supported its members when many of the club’s musicians couldn’t afford to play music fulltime, typically working factory, security, or apartment maintenance jobs on the side to make a living wage. Apartment maintenance jobs were especially desirable among musicians because they provided free living spaces in apartment buildings, where they could host their own tusovki.

In many ways, the presence of an official venue provided these musicians with a platform to step out of their underground personas while providing audiences with a more accessible space to see rock performances.

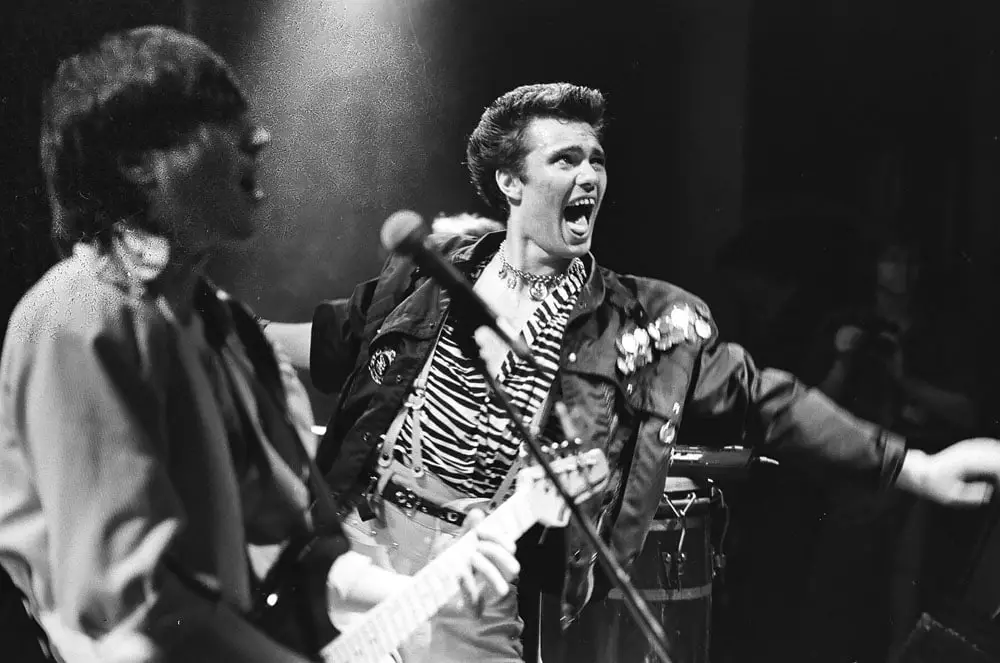

Above: Maik Naumenko’s “6 утра” (6 AM) channels a little Lou Reed, 1982.

The Music of Soviet Rock

Leningrad Rock Club’s member bands had to clear pieces with Party censors before performing, but often found ways of circumnavigating censorship. For instance, bands could clear content Party officials deemed unpalatable by dedicating it to political or anti-imperialist struggles that the Soviet Union supported, such as the Nicaraguan Peoples’ Liberation Movement. Other times, musicians could often pass their material off as comedy.

Nonsensical lyricism provided another expressive medium for Leningrad rock groups. Their unique and energetic style of lyricism captivated their younger audience while criticizing aspects of Soviet life. For instance, Странные игры’s “Метаморфозы” (Metamorphoses) provides lines like “I take a hat — // Turns out it was a frog. // I hug my wife — // But it’s [just] a pillow”. The song’s lyrics promise a logical thought but then surprise listeners with a zany conclusion. Some of Viktor Tsoi’s earliest hits also employ nonsensical lyricism as a way of connecting with an audience that grew up with the cultural cynicism of Stagnation. Songs like Tsoi’s “Алюминиевые огурцы” (Aluminum Cucumbers) circumnavigated censorship by using Aesopian language and lyrical absurdism while still engaging audiences with lyrics that elude the banality of working in a highly inefficient industrial model.

Above: Stranye Igri perform Metamorphoses in 1985

Other songs like Maik Naumenko’s “6 утра” (6 AM) preach a new wave of bard-like existence, encouraging play and relaxation. The song utilizes Leningrad-specific imagery like white nights, where “6 AM shines,” to construct a recognizable atmosphere for local listeners. The song’s ambient background guitar with almost spoken lyrics draws the audience into a more intimate listening experience but also mimics the styles of Lou Reed, frontman for The Velvet Underground, who influenced Maik’s composition and understanding of rock.

Lyrics in Viktor Tsoi’s “Бездельник №1”(Idler №1) portray more radical themes of cultural loafing alongside a sense of loneliness in Soviet society. Lines like “What is there to do next, I don’t know // No home. Nobody has a home // I’m surplus, like a pile of scrap” speak to the feeling of cultural disorientation in a society about which younger generations feel extremely cynical.

Above: Viktor Tsoi performs “Бездельник №1” (Idler №1) in 1986

Perestroika and Soviet Rock

Perestroika presented new problems for Soviet society. Drug abuse soared, and Western economic tactics proved disastrous in their implementation. The Soviet rock community was also hit by two particular tragedies in this period: Viktor Tsoi’s death in August of 1990, followed by Maik Naumenko’s death less than a year later, shook the Leningrad rock community to its core. Tsoi especially was a staple of the city’s rock scene, with a large fanbase that had fallen head over heels for his youthful lyricism and playful yet reserved demeanor.

Despite this blow to the community, local bands continued making music socially relevant to young people. AU’s “Огуречный лосьон” (Cucumber Lotion),” covers a scene that all-to-common in Perestroika’s deficit economy: a man waiting in line for wine at a grocery store who, upon arrival at the entrance, finds that the store is out of stock. He asks a nightingale where the wine went and receives the zany response, “In the department store, they’re selling cucumber lotion.” After the man slaps the bird against a road sign, the song’s chorus satirizes the deficit by overplaying the man’s love of the lotion he promptly sets off to buy.

The song sticks to playful Leningrad lyricism while displaying twisted folk imagery like a man beating a nightingale, often a giver of natural wisdom and helpful information in folktales. Scenes like this display a jaded cynicism and general unreliability of the well-known symbolism. For young people living through a tremendous and seemingly foreign shift towards democracy and capitalism, the song’s anecdotal slapstick humor provided a friendly voice of understanding to and unfamiliar post-Soviet life.

Soviet Rock Plays On

Leningrad rockers continue to hold a place in the world of Russian music, with groups like Странные игры still performing today, and have inspired groups like Ленинград (Leningrad). Fans of Viktor Tsoi can still see cover bands perform his hits at Котельная “Камчатка,” a museum and club established in the space where Tsoi worked as a maintenance man and held performances. The particular style of narrative rock established by these artists lives on today in a genre often called “Russian rock,” a term used in much the same way that “classic rock” is used in America.

For many children of the 1980s, these bands serve as a soundtrack of their youth, through Stagnation, Glastnost, Perestroika, hardship, and change. These bands provided an alternative to massified Soviet culture and pushed back against Party censorship within circles like the Leningrad Rock Club. Whether it was through nonsensical lyrics, the introduction of western music styles, or a general sense of self-determination among the musicians performing, Leningrad rockers altered the perception of what was deemed socially acceptable and became the soundtrack of a generation.