Shanson, especially as known in Russia, is full of contradictions and notoriously hard to define. Encompassing a range of musical styles, it incorporates bardic tradition and pop, with influences from rock, jazz, Slavic and gypsy folk traditions, vaudeville, cabaret, and “romance” – a Tsarist-era genre that loosely evolved from folk and opera.

An important part of shanson’s history stems from the criminal underworld, prisons, and labor camps from Tsarist times to present day. This influence gives some of the music rebellious anti-authority lyrics which often hail criminals as sympathetic heroes. These songs are often couched in coarse and/or graphic language. However, much of modern shanson focuses on love, everyday life, and even patriotism in lyrical modes that verge on the sickly sweet.

While hard to define, shanson has many passionate fans who listen to shanson radio stations and watch at least one shanson satellite TV station. Major television channels in Russia carry musical programs and documentaries focused on the genre and its artists. An annual, star-studded shanson awards ceremony is even broadcast on national TV, usually from inside the Kremlin, in the very building where Soviet lawmakers once met, just few feet away from Russia’s current presidential offices.

Below, we will look at where shanson came from and how it can be understood. We will also introduce you to several of its artists, listing them in the approximate order in which they first gained notoriety as shanson artists.

Introduction to Shanson

History by Josh Wilson and Max Bolotinsky

The term “chanson” was likely first applied to Russian songs in France by locals listening to the music of Russian-speaking political émigrés in the early 1900s. These songs were often lyric-driven, accompanied by simple instrumentation, and often socially- or politically-conscious. In French, “chanson” translates simply as “song,” and itself refers to a loose grouping of lyric-driven music genres. In France, it can refer to styles as different as cabaret, medieval bardic music, monastic chants, and some modern pop.

In Russia, Ukraine, and other former Soviet nations, the term only entered wide circulation in the early 1990s when the Soyuz record label and the producer Yuri Sevostyanov decided to promote “блатная песня” or “criminal songs.” The “блатная” genre, associated with the soviet gulag system, was rising in popularity in Russia’s free and turbulent 1990s. However, Sevostyanov and Soyuz felt that they could not focus a record division on “criminal songs.” High quality recordings and artists were too scarce, the market still too narrow, and they feared creating a potential public image problem by promoting something known directly as “criminal.”

Sevostyanov says that he plucked the term “shanson” from history to solve these problems. The French word (in slightly corrupted form) became a euphemism for criminal song and allowed him to build a more diversified genre, bringing in other types of formerly-repressed or socially-risqué music, such as the widely-popular bardic songs, under a single umbrella. It also conveniently dovetailed with commercial trends in the 1990s, applying an exotic foreign term and invoking a romanticized era.

Despite the term’s eventual success, it must be recognized that artists creating music before the 1990s would not have labeled their own music as “shanson,” but rather as other genres, particularly as “romance” and variations of “song” or “песня.”

Romance Music

Romance music was created by a fusion of opera and gypsy folk at a time when intellectuals were particularly interested in mining folk culture for inspiration in creating more nationally-defined high cultures. Developed in the 19th century, the Soviets initially decried it as a vestige of bourgeois culture. However, the popular music survived as “street genre” (уличный жанр) or “neighborhood romance” (дворовый романс – note that “дворовый” would actually translate to “courtyard,” a common fixture of Soviet-built housing communities). In these songs, singer-songwriters sang about love, humor, sorrow, current events, daily life, and anything else that affected their communities. Singers would often perform while playing a guitar, meaning that the genre also overlapped with bardic tradition.

As a “street genre,” the songs were partially reclaimed by the Soviets. Some singers even rose to stardom under the communists, raised by both popular public support and recognition as a genuine “people’s music,” so long as the songs avoided politics or directly supported Soviet ideals. Artists such as Leonid Utesov, Alexander Vertinsky, and Vadim Kozin largely defined popular culture in the 1920s, 30s, and 1940s, not only producing songs, but also often starring in films and participating in other cultural events.

The “street genre,” however, was only loosely connected to what would become shanson. In fact, Utesov, Vertinsky, and Kozin are generally listed specifically as shanson singers only by fans of shanson. They are most often classed under other popular genres of the time such as vaudeville, gypsy song, and estrada (a highly theatrical form of Soviet pop music).

Bardic Song and Sung Poetry

Many fans of shanson see “author-songs” (авторские песни), also known as “bardic songs” (бардовские песни), as a specific subset of shanson. Bards were especially popular in the Soviet underground of the 60’s and 70’s. Like many of the gulag singers, they wrote and performed their own lyric-driven songs, nearly always accompanied by just a guitar. Their songs were sometimes political and often socially-conscious. However, bardic song is much easier to classify as a genre and, unlike shanson’s often rough or emotional narratives, bardic music is appreciated as an intellectual and cultured genre. Thus, while there is some crossover between the shanson and bardic songs (such as with Alexander Rosenbaum), fans of bardic songs often bristle at shanson’s claims to the music.

Although not as important in Russia as in some other European countries, many performers of the genres covered here also created sung poetry – a genre that sets poems to music or at least treats lyrics as poetry.

“Blatnaya” Song

The darker and more direct parent of modern shanson is the “blatnaya song” (блатная песня). “Blat” is a Russian word that refers to the complex system of personal connections and exchanges of favors that, while officially illegal, provided the basic foundation for everyday interaction between the Soviet government and its citizens. “Blatnaya” can refer to just about anything criminal. These songs are often told from the first person, with the hero reminiscing about his/her former lifestyle, current situation, and of longing for freedom. The hero might be a thief, counterfeiter, petty or hardened criminal, or even a political dissident.

Most histories date the development of the core “criminal song” aspect of shanson to the 1500s. Prisoners in labor camps and serfs, who were in many ways prisoners of the estates that owned them, began singing new songs based on folk music. They sang of a longing for freedom, their experiences in captivity, and, for those in camps, how they were sentenced, often under unjust conditions.

Many variations of the style developed. During Russia’s Silver Age of poetry, Odesa criminal songs (Одесские блатные) told, in mostly cheerful songs, the stories of Odesa’s mafia culture. Today the term “Odesa shanson” (Одесский шансон) is used to refer to them. Before the revolution, White Guard members sung similar personal folk songs telling of the hardships and glories of military service in songs known simply as “military songs” (военные песни). The style continued, with modified content, in the Soviet army and modern Russian army. Likewise, today this music is often referred to as военный шансон.

Criminal song reached its modern development within the gulag system of the USSR. Under the Soviets, the population of prison camps exploded with hardened criminals mixed with artists, poets, and performers. Criminal song gained a more lyrical nature and took on stylistic influence from the more intellectual and refined romance music and bardic song to become what we know today as shanson. This is one reason why shanson lays retroactive claim to these genres as ancestors of its style.

Those prisoners who returned home brought songs back home that told of criminal culture, expressed political satire and dissent, or told about the conditions at the camps. Some listeners were shocked and confused by the complex prison slang often featured in these, but many others found it appealing, and as the popularity grew, the underground genre mixed further with more mainstream ones.

Performance of such songs was generally reserved for private groups and some efforts were made to mask authorship to avoid possible repercussions from the authorities. For instance, some songs were ostensibly about Tsarist prisons, but actually documented the authors’ own experiences at the gulags.

Arkady Severny dominated the blatnaya song genre in the USSR. Some even think he was the first to use the term “shanson” to describe his music. With his distinctly masculine, crooning voice, gypsy-influenced styling, and his rebellious yet often whimsical topics and lyrics, Severny became extremely popular through his private “apartment concerts” that were at times recorded on cassette tapes, reproduced, and distributed via the same “magnitizdat” process that the bardic and many early soviet rock performers used.

Post-Soviet Shanson

After the breakup of the Soviet Union, mainstream culture rapidly developed a marked taste for anything raw, uncensored, and extreme. Anything that felt as though it might have been censored in the past became widely popular in the present. Further, in the political and economic anarchy that overtook many of the former states, including Russia and Ukraine, crime rates and prison populations skyrocketed in the 1990s and early 2000s.

These forces coalesced into a wide popularization of criminal culture. Multiple TV programs such as Brigada showed criminals in a positive light. It was also at this time that Russia was widely introduced to American rap music, which is also known for its tendency to celebrate criminal life. Nearly anything associated with the world of crime in Russia became fashionable, such as ostentatious gold jewelry, leather jackets, track suits, and black BMWs.

The unity of the shanson and criminal worlds is perhaps best exemplified by the life and death of Mikhail Krug. Known for his expressive, soulful voice and tendency to sing songs riddled with prison slang (although he himself never served time in a prison), he became one of the most popular shanson stars of his time.

Krug’s repertoire mix was also very typical for his genre. It included older folk songs like “I Weep Bitterly” (“Я горько рыдаю”), about a man who has just received a jail sentence. Krug also sang many covers such as Igor Slutsky’s “Magadan” (“Магадан”). Krug’s own songs would be released and often re-released in new arrangements, often multiple times and sometimes creating new hits out of old. A “crooner,” his music focuses on his voice, with light accompanying music that shows heavily-synthesized influence from Russian folk, traditional Jewish music, and/or gypsy songs. His use of a stage name is also typical among criminal shanson performers.

Krug’s ties to the criminal world eventually led to his being murdered in his own house. His death only solidified his place in the history of Russian pop culture – and helped launch the career of Irina Krug, his widow, when she released an album of love songs dedicated to her late husband and began performing his repertoire.

Radio stations specializing in playing Shanson long indulged their listeners with controversial songs featuring obscene language. However, as the “wild 90s” passed, people began to press for civility and culture and the government gained the power to enforce it. In Kyiv in particular, the local shanson station was known as the music of choice for public transportation drivers, meaning that most of the city’s population was listening to its broadcasts at some time during the day. After many complaints about the explicit language content, city officials were obliged to ban the genre from being played by drivers. In Yekaterinburg, Russia, a destination city for many ex-convicts freed from the large penitentiaries in the Urals, a stronghold of shanson formed with the same problem and the same solution decreed by officials. These controversies, in addition to pressures exerted from an increasingly conservative public and advertiser base, prompted stations to alter their playlists and the push the more risqué examples of shanson from the air.

This had led to the development of what many call “post-shanson,” which has moved the genre away from criminality and towards mass-market pop. Maksim Leonidov, for instance, sings what are basically pop songs in a smooth and affectionate voice. His lyrics concentrate mostly on family and love. Mikhail Shufutinsky is popular inside and outside of Russia, and still carries the rough voice associated with shanson. However, he sings mostly of love and patriotism, remakes classic bardic songs, and occasionally sings about Jewish themes (he himself is Jewish).

In one other common confusion in shanson, there is an award called “Shanson of the Year,” which is not a singular, top award. Instead, it is simply a recognition of all #1 hits that have featured on Radio Shanson, a popular station in Russia. Other major awards, which are singular awards, include the Golden Gramophones, which covers the entire music industry in Russia.

The history of shanson has been convoluted. Its evolution has reflected the vast changes that have affect and continue to affect the post-Soviet space. It has become all the more dear to its listener base because of this.

Below are several artists to introduce you to the genre.

Alexander Vertinsky

(Александр Вертинский)

Biography by Nika Cooper

Alexander Vertinsky was a Kyiv-born poet, screen actor, composer, and considered a founder of the shanson genre, although he himself would never have known the term. Born in 1889 to a Russian noblewoman and a private attorney, Vertinsky had a difficult childhood after the early deaths of his parents. Separated from his older sister Nadya, he was told that she was dead, and raised by one of his mother’s sisters. Poor behavior in school resulted in Vertinsky being kicked out of his home and living on the streets. He worked any job he could to survive – from salesman to accountant.

Vertinsky showed an early interest in theater. His less-than-successful debut performance was hosted at the Pharmacists’ Club in Kyiv while he was still a student in high school. Later, he was hired as an extra at the Kyiv Solovtsov Theater while also writing theater reviews for local publications. He eventually secured the patronage of Sophia Zelenskiy, who had been a friend of his mother. Through her, he met artists such as Kazimir Malevich and Marc Chagall.

In 1910, Vertinsky moved to Moscow, where he found his sister Nadya working as an actress. Vertinsky joined dramatic and literary societies where he performed and directed. His big break came in 1912, when he secured the patronage of Saava Mamontov. With these connections, he began acting in plays and films and composing music for them.

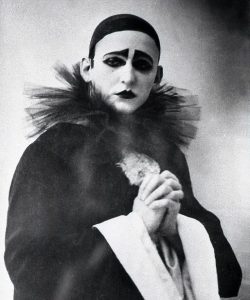

With the outbreak of World War I, he volunteered as a medic on the front where he first began to go by the name of “Pierrot” after registering for the army under that name on a whim. After being injured, he returned back to Moscow, where he continued acting in movies. He met actress Vera Holodnaya, the “Queen of the Screen,” on a set and fell in love. He began to compose songs for her, including one of his early famous songs in 1916 – “Your Fingers Smell of Incense” (“Ваши пальцы пахнут ладаном”), a romance song that proclaims that God himself would lead his love into heaven.

At about this time, Vertinsky began to perform at cabarets and mini-theaters as “Pierrot,” wearing clown makeup and costumes. As “Pierrot,” he would speak poems set to music he had composed himself. Often, the poems he performed were his own (such as “Your Fingers Smell of Incense”), but he sometimes also performed poetry by Aleksander Blok or Marina Svetaeva. His performance style was distinct for its hypnotic quality. He soon modified his makeup and costume to use only black and white. His songs evolved into small plays, complete with one or two characters and plots that often dealt with themes of loneliness. Vertinsky referred to his performances as “ariettes,” and they were extremely popular among both critics and the public. Vertinsky began to tour throughout the Russian Empire.

After the revolution, he returned to Kyiv for a time. Here, in October 1917, he wrote “That Which I Must Say” (“То, что я должен сказать”), a song lamenting the death and suffering of soldiers. The Cheka (ЧК), the counter-revolutionary committee of the Soviets, summoned Vertinsky to an interrogation over the song’s pacifist content and accusing him of having sympathy for the enemies of the Soviets. Vertinsky emigrated from the USSR in 1920 with the expressed goal of experiencing new adventures, a decision likely solidified by his troubles with the Soviet authorities. He was able to acquire (perhaps not legally) a Greek passport, and traveled and performed prolifically. First living in Poland, then Berlin, France, Palestine, the United States, and, finally, Shanghai, Vertinsky had little trouble wherever he went filling theater seats with Russian emigres. His time in France between 1925 and 1933 was one of his most successful periods. He befriended world-famous names such as Marlene Dietrich and Charlie Chaplin, and also wrote some of his best known songs, including “Madame, Leaves are Already Falling” (“Мадам, уже падают листья”) and “Tango of the Magnolia” (“Танго магнолия”).

In 1930s, Vertinsky began applying to return to the Soviet Union, likely due to his financial difficulties in Shanghai. He received an official invitation in 1937, but due to the start of World War II, the documents took six years to process. Finally, in 1943, Vertinsky moved back to Moscow with his new wife (a woman of Georgian descent whom he’d met in Shanghai) and his child. After the birth of his second daughter, Vertinsky wrote “Daughters” (“Доченьки”). He toured the Soviet Union, finding his popularity unfaded and giving over two thousand performances in fourteen years and eventually appearing in films again. His success came despite his difficulties with Soviet authorities – only thirty out of his one hundred songs were permitted to be performed, and a censor was always present at each of his performances. Additionally, newspapers would not write about him, nor did Soviet radio stations broadcast his songs.

Vertinsky died in 1957 shortly after giving a concert. Both of his daughters became famous actresses in the Soviet Union.

Vertinsky is today considered a founder of shanson primarily because his “ariettes,” or “song-novellas” pushed what would become “courtyard romances” to new narrative depths and increased their popularity. Vertinsky’s themes never dealt with criminality (aside from mournful songs about the lives of prostitutes), nor did he ever serve time in prison despite his struggles with Soviet censorship. However, his classic songs were eventually grouped together with criminal songs in the creation of the shanson genre.

Arkady Severny

(Аркадий Северный)

Biography by Josh Wilson

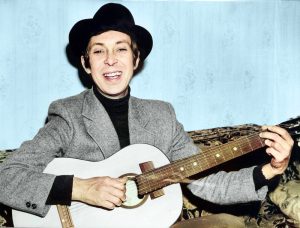

Arkady Severny, born Arkady Dmitrievich Zvezdin in 1939 in Ivanovo, USSR, is a legendary figure in the world of Russian underground music, particularly in the criminal song genre. “Severny” was a pseudonym, apparently chosen as many of the USSR’s most feared gulags were located in its northern regions. A largely self-taught musician, he had always been drawn to street romances and criminal songs as well as putting the words of great Russian poets to music. He performed, often in vaudeville-like styles, in nearly every genre that would eventually coalesce into shanson.

Severny got his start in the 1960s, performing unofficially at private gatherings, often accompanied by small ensembles of jazz or guitar musicians. His distinctive baritone and wide repertoire captivated his audiences. His earliest recordings were made with Rudolf Fuchs. Fuchs was a “collector,” a person who specialized in collecting and selling banned, forbidden, or uncensored counter culture. Collectors also organized illegal concerts.

Severny’s first major recording with Fuchs was produced as a fake “state concert,” scripted to sound as though it were recorded from a Soviet radio station in Siberia “by the popular demand of its listeners.” The hoax helped add considerable mystique around the recording and eventually it became so popular that Fuchs developed it into a style he called “theater in front of a microphone,” with Severny running through a wide variety of songs, poetry, jokes, and stories, all told in his captivatingly distinctive voice.

Fuchs also introduced Severny to other collectors, and Severny traveled widely, giving concerts in small, private venues and recording thousands of songs. Although he did not write most of the material himself, many of his interpretations became definitive. Fuchs and many other collectors eventually served jailtime for their illegal “entrepreneurism,” but Severny avoided repercussions in part because his music was popular with the police and authorities. Even when he was taken in for not having proper registration of his residence in Moscow, he was let go without charge. In fact, while he never performed on state television or radio, his popularity rivaled that of state-sponsored pop stars.

Severny’s life was not particularly happy. By the time he died at the age of 48, he had been divorced twice and had struggled with alcoholism for many years. A stroke took him in 1980, brought on in part by pneumonia and hypertension caused by stress and alcohol. In post-Soviet Russia, he has been recognized as a pioneer of shanson and many contemporary performers cite him as a key influence.

Mikhail Shufutinsky

(Михаил Шуфутинский)

Biography by Josh Wilson and Julie Hersh

Mikhail Shufutinsky is a Russian jazz and shanson star. Over his decades-long career, he has been praised as a singer, an instrumentalist, and as an artistic director and producer.

Growing up in postwar Moscow, he was drawn to music from early childhood, learning to play the accordion as well as the Russian traditional bayan and the piano. In his teen years, he performed with various jazz groups in Moscow cafés. He got his higher education in music as well, with specializations as a director, choirmaster, and singing teacher.

After graduation, he formed an instrumental group and began playing backup for various pop stars, touring the USSR with Mosconcert, the official Soviet concert organizer. He eventually took a residency in a restaurant in Magadan, a port city in the USSR’s far east, that was a terminal point for Siberian raw materials and any related freed prison labor. There, Shufutinsky began singing himself rather than just playing instruments.

Returning to Moscow in 1975, Shufutinsky became the artistic director of the pop group Akkord (Аккорд). He soon moved on to another group, Flow, Song (Лейся, Песня), altering their membership and repertoire and creating one of the USSR’s most popular musical groups of the 1970s. However, as his profile grew, so did his feeling that the authorities were watching him, including for issues like his trademark beard and the fact that he is a Jew.

Shufutinsky’s website says that he was simply unable to live under the “rules and principles of life in the Soviet Union.” He immigrated to America in 1981 and quickly found work with other artists in the Russian diaspora, at first in New York and then in Los Angeles. He initially worked mostly in production and playing backup instrumentation. He also returned to singing in restaurants. Perhaps most importantly, in 1983 he released Escape (Побег), his first solo album, which consisted mostly of covers of folk, prison, and criminal songs with synthesized instrumentals.

The record was a success and he formed a band, Ataman, to accompany him. He then released nearly thirty more albums over the next four decades in addition to collections, singles, and other material. When perestroika came, he was able to distribute his music in Russia, becoming a best-selling artist there throughout the 90s. In Los Angeles, he started a production company and has helped many other artists achieve fame.

In 1993, he released Kitty, Kitty (Киса-Киса), with the hit “Jewish Tailor” (“Еврейский портной“), a song by Alexander Rosenbaum that once had to be performed under the title “The Old Tailor,” as openly discussing Jewish culture was taboo in the USSR. Shufutinsky arranged it with music heavily influenced by Jewish folk. This song connected especially with his fans in the US, many of whom were Jews who had fled the USSR.

In 1994, he released Soul, Walk Free (Гуляй, душа), which gave him his seminal hit, “The Third of September” (“Третье сентября“), a passionately sentimental song originally written by Igor Krutoy, a writer, producer, and occasional performer. Shufutinsky does not write his own material. However, his versions have often become definitive for the songs he performs. He has been at the top of the shanson charts for the majority of his career.

Today, he maintains residences and audiences in both America and Russia. He was named a Distinguished Artist of the Russian Federation in 2013, one of the highest civilian honors. He has been careful not to speak about Russian-Ukrainian War, although he did once perform at a hospital treating Russian soldiers wounded in the war in 2022.

Willi Tokarev

(Вилли Токарев)

Biography by Liv Whitmore

Willi Tokarev became a breakout star first in Murmansk for his humorous lyrics and stylized criminal songs. The height of his career would come while living in Brighton Beach, New York. He incorporated experiences as a Russian emigre in the US into his songs – giving them a unique niche within the shanson genre and an added mystique with audiences in Russia.

Born Vilen Ivanovich Tokarev, in Chernyshev, 1934, Tokarev’s unusual first name was not uncommon then. To show their dedication to the Communist Party, parents named their children for its heroes and concepts. “Vilen” is short for V. I. Lenin. Growing up in Russia’s Caucasus region, at age five he organized a neighborhood children’s choir, and by eleven had published his first poem in the school newspaper. By fourteen, young Tokarev was composing melodies for folk string instruments.

After working on a ship and later serving his compulsory military service, he moved to Leningrad and entered the Leningrad Conservatory as a string musician, studying the jazz double bass. He joined the Anatoly Kroll Orchestra as well as several ensembles such as the prestigious Friendship (Дружба) Ensemble. Friendship released several recordings, including in foreign languages such as the Italian classic “Volare,” (“Воляре”). While still studying, he recorded his first solo songs, including “Rain” (“Дождь“) and “Winter Song” (“Зимняя песенка“). However, he primarily wrote music for others.

With rising fame, he was invited to join the Leningrad Radio and Television Orchestra to play under jazz legend David Goloshchekin. However, jazz soon became a target for censors and an order from Moscow prohibited “more than three syncopations” in a single piece of music, effectively outlawing jazz. Tokarev, now fearing for his safety in well-monitored Leningrad, moved to Murmansk in 1970 to continue his career. There, he had his first hits like “Murmanchanochka” (“Мурманчаночка”) or “Dear Murmansk Girl.”

Still seeking greater security, Tokarev emigrated to the US in 1974, arriving in Brighton Beach penniless and with extremely limited English. He bounced from job to job, eventually finding stability as a taxi driver. After five years of saving he amassed enough savings to record and release his first album in 1979, called And Life, It Is Always Beautiful (А жизнь, она всегда прекрасна). The album was much more lyrical than his later work and went relatively unnoticed. He found a foothold in the Brighton Beach music scene only with his second album, In a Noisy Booth (В шумном балагане) in 1981. This record leaned into shanson, filled with humorous songs that paid tribute to both the Russian criminal underground and the unique culture of the New York’s Russian-speaking diaspora. In a Noisy Booth gave him many of his biggest hits including “Skyscrapers” (Небоскрёбы), “New York Taxi Driver” (Нью-йоркский таксист), and the album’s title song. “New York Taxi Driver” speaks to his exploration of his identity as a Russian living in the U.S.; he laments the dehumanization of American capitalism and the lack of community he felt in his first years abroad.

Tokarev sang in restaurants and continued releasing music such as the albums Over the Hudson (Над Гудзоном) (1983), Gold! (Золото!) (1984), and The Trump Card (Козырная Карта) (1986). By the late 1980s, he began touring the Soviet Union and in 1996 he returned permanently to Russia, settling in Moscow for the rest of his life. He started singing about Russia, including flaterringsongs about the Mayor of Moscow as well as Vladimir Putin’s wife. His popularity continued.

Tokarev sang of crime and was a known associate of prominent criminals in both Russia and New York—when interviewed on the subject, he said, “I often perform for [criminals], I visit their establishments. Among them there are very good, decent people.” (“Я часто перед [криминальными] выступаю, в их заведениях бываю. Среди них есть очень хорошие, порядочные люди.”) During his Brighton Beach period, “Guitar with a Cracked Deck” (Гитара с треснувшею декой) off of the album Gold! is sung from the perspective of a prisoner in a Siberian labor camp and tells of the fear, hopelessness, and isolation of life in the gulag. Meanwhile, Champ-dollon (Шан-долон), recorded in Russia, is a collection of just criminal songs. Notable examples include “On the Run,” (В бегах) “Letter from the Zone,” (Письмо из зоны) and “Free Again” (Снова на свободе).

Willi Tokarev kept performing into his 80s, and he released over 48 studio albums as well as five compilation albums before his death in 2019.

Aleksandr Novikov

(Александр Новиков)

Biography by Ana de la Llave

Aleksandr Novikov is a renowned singer, bard, poet, and Russian shanson performer, known most his urban romances. Novikov blends classical romance styles with ballad-like structures to produce many influential works.

Novikov was born in 1953 into a military family on Iturup Island in the Kuril Archipelago. He and his family moved many times before settling in what is now Yekaterinburg. Novikov did not do well in school and would often go against authority. As early as his teen years, he was openly anti-Soviet, and would remain so the rest of his life. He served a short amount of jail time for petty crimes throughout his youth.

In 1967, Novikov watched Vertical, in which bard Vladimir Vysotsky performed five of his own songs. Inspired, Novikov began performing as well, and was even expelled from the Ural State Technical University for performing an unauthorized Beatles hit at one of the institute’s events.

By the late 1970s, Novikov was performing in restaurants and managing a studio-workshop. He also founded his own recording studio, Novik-Records, in 1981. He released his first album, Rock Polygon (Рок-полигон), with his band by the same name in 1983, with influences from rock and roll, reggae, and new wave. Shortly after recording a second album with Rock Polygon in 1984, he switched genres to record his first urban romance album, Take Me, Cabby (Вези меня, извозчик). Many of its folk and gypsy influenced songs became instant hits and staples of the genre.

The album got Novikov arrested for supposed anti-Soviet lyrics. For example, although he was not Jewish, the song “I Come From…” (“Я вышел родом…”) is about his upbringing in the Jewish Quarter in what used to be Sverdlovsk, modern-day Yekaterinburg, and he sings affectionately of the Jewish friends he had there. Finding they could not convict him on the original charge, the authorities instead accursed him of “falsification of musical equipment.” He was sentenced to ten years in prison, but served only six, being released early after a court overturned his sentence.

Many of his works after his release, like the song “I Remember, My Love” (“Я помню, любимая”) and the album Pineapples in Champagne (Ананасы в шампанском), consist of lyrics based on the poetry of Sergey Yesenin, as well as other Silver Age poets. Others, like “Shansonette” (“Шансоньетка”) are rougher – for instance, about the attraction felt for a stripper. Many of his other works have become classics of the genre, like 1991’s “Ancient City” (“Город древний”) and 1996’s Remember, Girl (Помнишь, девочка). Many of his recent albums have repurposed his discography to keep his music alive with old and new fans of shanson alike. He also re-recorded many of his own, older songs, to great success. His 2012 “Break Up with Her” (“Расстанься c Ней”) received a hit remix on the 2021 album Bomb (Бомба).

In 2010 he was appointed artistic director of the Ural Variety Theater. He has also won the Shanson of the Year award 18 times over the span of his career, the most recent being from 2024.

Throughout his life, Novikov has often been at odds with authority, with his most recent incident being a residential coop accusing him of embezzlement in 2019, but the prosecutions were terminated. His politics have also remained hard to pin down. He supported Russia’s invasion of Ukraine in 2022 but in the past has supported political campaigns opposing Vladimir Putin. He remains an active performer in Russia today.

Mikhail Krug

(Михаил Круг)

Biography by Ana de la Llave

Mikhail Krug is perhaps the most popular modern singer of criminal songs. As a singer-songwriter, performer, and composer, he also sang romance songs and ballads. Often praised for his “from the people” perspective, he was known to have the respect of criminal gangs who counted themselves as fans.

Born Mikhail Vladimirovich Vorobyov, he grew up in Kalinin, now modern-day Tver. He initially took accordion lessons, but, at 11 years old, found his calling in the guitar. He wrote poems and performed covers of Vladimir Vystosky at parties as a teenager.

In 1987, after he was discharged from the army, he placed first in a singer-songwriter contest with “About Afghanistan” (“Про Афганистан”), dedicated to the Soviet soldiers that fought and died in the Soviet-Afghan war. He then devoted himself to songwriting and adopted the pseudonym, Krug. “Krug” means “circle” in Russian and is commonly used to refer to one’s close friends and relatives. Criminals also use the word to refer to close associates.

His first album, 1989’s Tver Streets (Тверские улицы) was never officially released. He gained fame as copies were duplicated by fans and later professional pirates selling tapes at markets. Krug gave his blessing to these pirates, saying it aligned with the significance of shanson itself. Most of Krug’s income came from live performances.

Krug’s first officially-released album was 1994’s Gangster-Lemon (Жиган-Лимон). “Lemon” is still slang for “Million” in Russian and refers to riches. This album contained an older song that is still one of Krug’s signature hits, Good Girl (Девочка-пай), whose name also relies on contemporary slang. It is a humorous song that tells of a good girl who falls in love with a criminal.

Krug’s most famous work, “Vladimir Central” (“Владимирский централ”) from his 1998 album Madam (Мадам), is perhaps the best known song of the shanson genre. It tells the story of a prisoner in the infamous Vladimir Central Prison, lamenting his love lost to his life of crime. Shortly before writing the song, Krug had met Alexander Severov, a gangster who was serving time at Vladimir Central. Rumors circulated that the song was about Severov. Krug and Severov maintained a friendship until Krug’s death. Krug never served time of was directly aligned with a criminal gang, but his open connections to criminals likely aided him in his artistry.

Krug toured throughout Russia and internationally, mostly for emigres in Germany, the US, Israel, Ukraine, Belarus, Estonia, and others. He was known for charity concerts and particularly for performing in prisons. He appeared on TV in numerous variety shows singing, for example, duets like “Let’s Talk” (“Давай поговорим”) or “Come to My House” (“Приходите в мой дом”). In 1995, he starred in a documentary called Bard Mikhail Krug (Бард Михаил Круг). In 2000, he appeared in the film “April” (“Апрель”) playing a crime boss.

At the height of his career, on the night of June 30, 2002, Krug was shot by two assailants in his home and died the next day at Tver City Hospital. His killers were only identified in 2008, when his wife, Irina, was able to identify one who was brought to her attention from the still-ongoing investigation. In 2012, she identified the second from a photograph, although he had apparently been murdered by a third criminal in retribution for killing Krug. In 2019, the first assailant, serving a life sentence, admitted that the Tver Wolves gang intended to rob Krug’s home while the family was away, steal valuables, and then, when Krug learned of the robbery, offer him protection in exchange for a cut of his concert proceeds. However, the family returned home unexpectedly early and the plan turned tragic. Thus, in an ironic twist, Krug was killed by the very criminals he romanticized in his music.

Krug did not avoid offending people. Married three times, he was known for numerous affairs and often dramatic breakups. He held strong and often loudly voiced opinions about communists, feminists, other artists, and other groups and individuals. He passionately defended shanson, including against Russian officials who derided it for glorifying criminals. In his last years, he served as a cultural advisor to controversial populist politician Vladimir Zhirinovsky, which gave Krug connections in the Russian State Duma.

Over his career of about 15 years, Krug released 14 albums, 12 collections, and several concert recordings. Since his death, still more collections, recordings, and at least four tribute albums have been released.

Though Krug’s death was sudden, his memory, mystique, and legacy lives on. His wife took up his discography and stage name after his death, performing as Irina Krug. His grave in the Dmitrovo-Cherkassy Cemetery near his home town of Tver is a pilgrimage site for shanson fans.

Sergey Nagovitsyn

(Сергей Наговицын)

Biography by Liv Whitmore

Sergey Nagovitsyn was known for incorporating elements of pop and disco to shanson, creating a more sophisticated, richer sound, while staying true to the themes and lyricism for which shanson is known. In an interview, asked about his artistic influences, Nagovitsyn ranked them in order of importance: “[Vladimir] Vysotsky, [Aleksandr] Severny, [Alexander] Rosenbaum and [Aleksandr] Novikov.” Nagovitsyn was also a fan of the rock group Kino, incorporating some of their style into the distinctiveness of his own.

Born in 1968 in Perm, Nagovitsyn’s childhood shaped his later musical career. Criminal activity, violence, and alcoholism were commonplace in the industrial city, as was “gangster romance” (блатная романтика), a subgenre of criminal song. These elements became a source of nostalgia for the singer later in life, likely contributing to his interest in criminal songs.

Despite finding school difficult, Nagovitsyn earned high enough marks to be accepted into the Perm Medical Institute. There, he began playing guitar and writing music. Less than a year later in 1986 he was summoned to the army, where he played avidly with a band formed with fellow soldiers, writing dozens of songs. Unfortunately, none of his work from this time was saved.

After his discharge, the singer returned to Perm. Deciding not to return to medical school, he got a job with the city’s gas service and formed a new rock band, Train (Шлейф) with his coworkers. Their first album, Full Moon (Полная Луна), was released in 1991. A Moscow-based production group called Russian Show (Русское Шоу) took notice of the young Nagovitsyn as the frontman of the group and invited him to the capital to create a solo album. Though the singer arrived excited, disagreements with the recording studio saw him leave Moscow just six months after his arrival with the album never completed. He returned to Perm and eventually released a solo record on his own in 1993. The work, titled City Meetings (Городские встречи), is mostly romance songs. Its titular single remains one of his most popular works.

With Nagovitsyn’s third solo album, Dori-Dori (Дори-Дори), the St. Petersburg station Radio Russian Shanson (Радио Русский Шансон) began playing his music throughout Russia, with the title track becoming a well-known hit.

Nagovitsyn’s personal sound leaned further into criminal shanson as his career progressed. Two of his most famous later songs “Lost Land” (“Потерянный край”) and “White Snow” (“Белый снег”), both featured on his final record, Broken Fate (Разбитая судьба), sing of machine guns, shackles, and longing for freedom. He also still sang many upbeat criminal hits such “Farewell, Koresha” (“До свидания, кореша“), “Without Prostitutes and Thieves” (“Без проституток и воров),” and “There on the Trees” (“Там на ёлках“) although the lyrics are often bittersweet.

Tragedy struck on December 20th, 1999, when the singer died of what is thought to have been a heart attack at the age of 31. His premature passing was likely due to heavy drinking and tobacco use, which had been exacerbated by depression, a result of his guilt over his involvement in a fatal traffic accident. Sergey Nagovitsyn is buried in Perm at the Zakamskoye Cemetery.

Active in music from 1991 until his death at the age of 31 in 1999, he released a total of six solo albums. Three additional albums, featuring songs recorded before his death, were released by relatives in the early 2000s.

Grigory Leps

(Григорий Лепс)

Bio by Josh Wilson and Julie Hersh

Grigory Leps is hailed as one of the greatest living practitioners of criminal shanson, although he has lately turned to more main-stream soft rock.

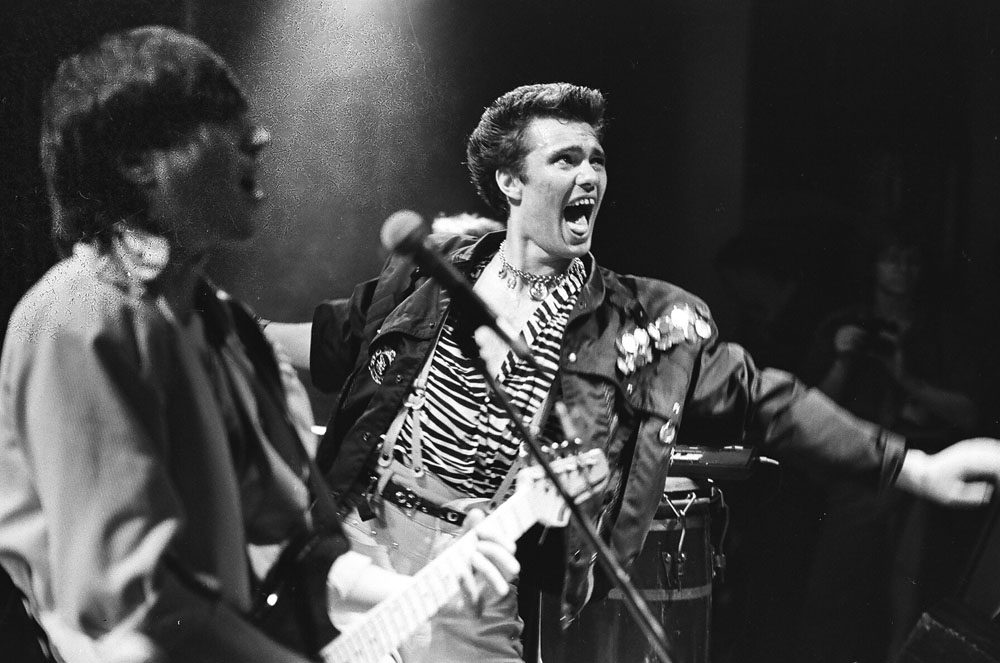

Born Grigory Viktorovich Lepsveridze, he took the stage name “Leps,” as his ethnically Georgian last name was hard for most to pronounce. Known for his vocal range, he was initially the lead singer for a perestroika-era electronic rock band called Index-398.

After the fall of the USSR, Leps began a solo career performing romances at restaurants in his native city of Sochi. He eventually landed a regular spot singing at the restaurant located inside the upscale Hotel Zhemchuzhina, a favorite with stars from Moscow visiting or touring the popular resort area. He was encouraged to take his talent to Moscow by shanson and estrada stars like Oleg Gazmanov, Mikhail Shufutinsky, and Alexander Rosenbaum. He also made connections with underworld actors who frequented the hotel. Leps made good money there, but tended to spend his earnings on gambling, liquor, and drugs.

His first album, Grisha Sochenskii (Гриша Сочинский) takes its title from a stylized version of his name, using a diminutive of his first name and adjectival form of his home city, a common form of nickname in the criminal underworld. The album has songs about gangsters and prisons, sang with a synthesized jazz-influenced accompaniment. The release did not find immediate traction and, in 1992, he took the advice he received to move to Moscow. He did so, in part, with the patronage of Iosif Kobzon, an estrada singer long suspected by the FBI to have ties with the Russian mafia.

In 1994, he recorded his second album, God Keep You (Храни Вас Бог), which took on a less heavily synthesized, less growling, and much more romantic tone. It gave him his first hit, “Natalie” (“Натали“).

Based on the success of his second album, he began to get offers for concerts and TV appearances. However, his addictions did not slow and he developed health problems, leading to pancreatic necrosis in 1995. He survived surgery for this and has reportedly been sober since, but now experiences chronic health problems.

His fourth album, the rock-influenced On Strings of Rain… (На струнах дождя…), gave him his signature hit, the moody and poetically soaring “A Glass of Vodka on the Table” (“Рюмка водки на столе“), written by fellow shanson artist Evgenii Grigorev, also known as Zheka.

Since that time, he has called himself a “soft rock” artist. However, even his modern music continues to retain elements of shanson, and he is in regular rotation on Radio Shanson and at shanson festivals and concerts. This can be said of his largely positive album Pince-nez (Пенсне), which includes the hit track “The Very Best Day” “Самый лучший день,” which was the theme song for a comedic movie of the same name. It is also true of the rougher Gangster #1 (Гангстер №1) with its rough drinking song “Glasses” (“Стаканы“) and his most recent single, 7000 Hearts (“7000 сердец“), an ode to fallen WWII soldiers.

Leps has long been barred from entering the US due to his suspected ties to organized crime. He is also now barred from most of Europe due to his outspoken support of Vladimir Putin and the war in Ukraine.

He continues to perform and release music in Russia. In 2011 he was named a Distinguished Artist of the Russian Federation. He’s also been awarded Shanson of the Year and Golden Gramophones several times. Since 2012, he has run his own production company.

Stas Mikhailov

(Стас Михайлов)

Bio by Josh Wilson and Zachary Hicks

Stas Mikhailov is most associated with what has now become known as “post-shanson.” It avoids criminal themes and is consistently lyrical and highly sentimental.

Born Stanislav Vladimirovich Mikhailov, he started out life as a classic restless dreamer. He began music school twice and flight school once, but never finished any of them. In the 1990s, he launched multiple business ventures and moved his family between Moscow, St. Petersburg, and his native Sochi as he sought success. All the while, he worked at music, dreaming of becoming a shanson star.

His first song, “Candle” (“Свеча“), which he worked on for more than a year, was released in 1992. Shortly thereafter, he released a solo album of the same. Heavily influenced by jazz and 90s electronic, his songs were mostly about love. Neither his single nor his album gained traction at the time.

His first success came only in 2000, when his single “Without You” (“Без тебя“) got national airplay. It was eventually released on his third, but first successful album, The Call Signs of Love (Позывные на любовь) in 2004. This effort was much more influenced by rock, while still carrying electronic elements and highly sentimental lyrics.

By 2006 he had a successful performance at the 3500+ seat October Concert Hall in St. Petersburg. That year also saw the release for his fourth album, The Shores of a Dream (Берега мечты), which included what has become his signature hit, “Everything for You” (“Всё для тебя“). While maintaining the influences of past albums, Shores returns to a more lyrical base and pop-shanson foundations. The album ends with “Wait” (“Жди“), an example of modern military shanson that tells of a soldier at war, longing for his love back on the home front.

After 2006, Mikhailov’s success was exponential, with concerts at the 6000+ seat Kremlin Palace and other major venues. In 2009, he won his first Golden Gramophone for “Between Heaven and Earth” (“Между небом и землей“). In 2010, his album Alive (Живой) topped Russia’s charts for most copies sold. Alive featured “Let Go” (“Отпусти“), for which he won his second Golden Gramophone. In 2010, he was named a Distinguished Artist of the Russian Federation by then-president Dimitry Medvedev. In 2011, Forbes named him Russia’s most influential celebrity, unseating internationally-known tennis star Maria Sharapova.

Today, Mikhailov remains one of Russia’s most commercially successful artists. He is both celebrated and often skewered, including on popular comedy shows, for everything from his overly-emotional music to his physical appearance, which has grown ever-more masculine with time. He has also grown more openly religious in his comments and lyrics.

As of 2022, his career has been largely confined to Russia and Belarus as he has been a long-time supporter of President Putin and now publicly claims that God will see that Russia wins the war in Ukraine. He continues to give regular concerts in Russia and consistently releases new music, such as “Know” (“Знай“), released in 2025 ahead of a concert to honor his 55th birthday.

Evgenii Grigorev (Zheka)

(Евгений Григорьев; Жека)

Bio by Liv Whitmore and Josh Wilson

More commonly known as Zheka, Evgenii Gennadyevich Grigorev is a celebrated singer-songwriter who has penned many songs for others. His career has tracked shanson’s transition to post-shanson, eschewing directly criminal themes and eventually embracing more poetic and lyrical styles.

Born in 1966 in Kurgan, Russia, Grigorev showed creativity early, first learning the domra in school, then playing drums in a rock band he formed at fifteen. After his compulsory military service, he pursued business ventures in Kurgan in the 1990s, co-owning a restaurant and later opening a music studio. In 1995, he wrote the smash hit “A Glass of Vodka on the Table” (“Рюмка водки на столе“), selling it to Grigory Leps for $300—a considerable sum for him at the time. When the 1998 financial crisis ruined his businesses, he moved to Moscow to pursue music full-time.

He lived very cheaply and recorded an album at night at a friend’s studio. He sent songs to Radio Shanson was already getting airtime and performance invitations by the time that his popular first album, Pine-Cedars (Сосны-кедры) was released. Two of his early hits “I am Like an Autumn Leaf,” (Я, как осенний лист) and “I’m Sorry,” (Прости) have remained mainstays of his stage repertoire.

By 2006 he was successful enough that he retrieved the rights to “A Glass of Vodka on the Table,” and not only recorded it himself, but also released an album of the same name. has since remade the song himself and, in fact, released an album of the same name in 2006.

Most of his early albums leaned heavily into shanson style and his personal image projected a classic Russian mafia-style street hooligan, with a gravely voice, felt cap, and ever-present cigarette and/or bottle. However, he never embraced truly criminal shanson. Many songs cover drinking, such as “A Glass of Vodka,” but the vodka is featured only once in a song that is otherwise about loss and loneliness in a poetic night. Many other songs discuss murder, like “Taxi Driver” (“Таксист“), or theft, like Kurgan (“Курган“) or instance, but only in their senselessness.

In 2006, he briefly joined a planned supergroup, The Four Card Suits (Четыре масти). The collaboration produced only one album, known as First Album: Super Project of the Year (Первый альбом – супер проект года), and a single major concert before being abandoned.

As his career has progressed, he has gradually shed the hooligan image, preferring to emphasize his clean shaved head and usually appearing in a spotless white shirt. Most of his more recent hits are about love, such as “Drink Wine with Her,” (“Пить с ней вино“) or “Charter to Love” (“Чартер на любовь“). Many have also dived deep into poetic explorations. For instance, Cuckoo (Кукушка), is an aching song about the fickleness of fate, framed as a discussion with a cuckoo, who is known in Russian mythology as a harbinger of spring and renewal, but also of deception and death for it’s tendency to steal nests from other birds. Cuckoo is Zheka’s biggest hit to date.

He has released twelve total solo albums to date, with his most recent, Thank You for Everything (За всё тебя благодарю), released in 2025. He also composes soundtracks for films and television and continues to tour and appear on television and radio programs.

Katya Ogonyok

(Катя Огонёк)

Biography by Nika Cooper

Katya Ogonyok was one of the most prominent women of shanson. She was known from writing and performing criminal songs from a female perspective.

Born Kristina Penhasova in 1977 in the small coastal village of Dzhugba near the Black Sea, her mother was a dancer and her father was Evgeniy Penhasov, a musician in the band Samotsvety. Ogonyok grew up attending music and choreography classes.

She recorded her first album at just fifteen years old. Her father knew Alexander Shaganov, a songwriter well-known for hard rock hits, and convinced him to write for his daughter. Although that album was never published and seems to have been intended for friends and family, Ogonyok was encouraged. After finishing the ninth grade at the age of sixteen, she moved to Moscow where she briefly sang with the teenage pop band “10A,” a project Shaganov was also involved with. Wanting something more serious, Ogonyok then joined the well-known shanson group Lesopoval (Лесоповал) as a backup vocalist. It was soon decided, however, that Ogonyok’s feminine, youthful voice clashed with the band’s masculine image.

In 1995, Ogonyok won a shanson contest run by Union Production, which earned her a record deal. Now 18, she adopted the pseudonym “Masha-Sha,” to collaborate with successful shanson singer Mikhail Sheleg, who already went by “Misha-Sha.” The two sang lewd songs with sexual themes and low-brow humor. They released two albums in 1998 – Misha+Masha=Sha!!! (Миша+Маша=Ша!!!) and Masha-Sha – Rubber Vanyusha (Маша-ша — Резиновый Ванюша). The best known hit from this collaboration, “Rubber Vanyusha” (Резиновый Ванюша), literally translates as “Rubber Ivan,” but is, in fact, about a vibrator.

After three years of this collaboration, Ogonyok wanted to get away from her ditzy, sexualized “bad girl” reputation and be taken seriously as an artist. She changed her pseudonym to Katya Ogonyok and turned to criminal shanson. Working with a new composer, Vyacheslav Klimenkov, Ogonyok began to sing emotional love songs from the perspective of a woman in prison, the first musician within the genre to do so. To build her new persona’s credibility, she and her new producer casually spread rumors that she had spent two years in prison for a traffic accident, a myth that lingered for many years.

Her new take on the genre soon generated hits. Despite never actually spending time in prison, her songs became hits starting with White Taiga (Белая тайга) and White Taiga II (Белая тайга II) released in 1998 and 1999, respectively. The most popular song from the two albums was “I Envy You” (“Я ревную тебя”), a tragic song about a woman thinking of her partner waiting for her at home. She expresses gratitude for his love, which helps her survive her time in prison, and wonders how he is doing without her.

In 1999, Ogonyok performed on the television program Legends of Russian Shanson (Легенды русского шансона). She continued to be prolific in the genre, releasing three albums in 2000 alone with hits such as “Love” (“Любовь”). The same year, she began to work with a new producer, Vladimir Chernakov, with whom she would record another eight albums. This included a self-titled album called Katya (Катя) in 2005. The title track is a seemingly cheerful song with a chorus that chants her name, but the verses reminisce on a better time before her heart was wounded. She continued to produce hits throughout her career, such as “Payoff” (“Прикуп”) in 2002, in which she pines for a lover who is serving time in prison, and “I Can’t Make It Without Him” (“Я не могу без него”) in 2008, her second-biggest hit. In interviews, she stated she was heavily influenced by jazz and soul musicians, such as American singers Stevie Wonder and Ella Fitzgerald, as well as by Soviet singer Lidia Ruslanova, a folk romance singer.

In 2007, when she was only thirty years old, Ogonyok passed away in a Moscow hospital due to heart failure and pulmonary edema. Her death was unexpected due to her young age, and there are conflicting reports about her death – some newspapers reported that she had a chronic liver disease, others that she had epilepsy, both possible conditions that could have contributed to the fatal heart attack. Despite her early death, her influence on Russian shanson had a long-lasting impact. In both 2013 and 2016, concerts were held in her honor to commemorate Ogonyok and her music.

Irina Krug

(Ирина Круг)

Biography by Ana de la Llave

Irina Krug is a pop-shanson singer-songwriter and the widow of famed shanson artist Mikhail Krug. She launched her career after his death, and would eventually sing a mix of covers of her own music and Krug’s, both his hits and his unfinished songs which she completed.

Born in 1976 as Irina Viktorovna Glazko in Chelyabinsk, she grew up wanting to be an actress and was part of a local theater group. She was working as a waitress when she met Mikhail Krug in 1999, where he offered her a job as a costume designer. Two years later, they married, and she became a housewife, taking care of his son from a previous marriage, her own daughter from a previous relationship, and eventually bearing Mikhail a second son, Alexander.

After her husband’s death in 2002, Irina took the unusual step of legally changing her last name to Krug, matching her late husband’s stage name. She was greatly supported by her late husbands’ contacts in the music industry who helped her kick off her career.

Her debut album, The First Autumn of Separation (Первая осень разлуки), was released in 2004 with the help of Mikhail Krug’s old friend, Leonid Teleshev. It is composed of songs dedicated to Irina’s late husband, including covers of Mikhail’s songs, and duets sung with Teleshev. She was nominated for the “Discovery of the Year” award and had a number one hit with “Autumn Café” (“Осеннее кафе”) in 2005. That same year, she also graduated from Tver State University with a degree in management.

Her follow-up 2006 album To You, My Last Love (Тебе, моя последняя любовь) also focuses on mourning her husband. It features melancholic and bittersweet songs focused on loss, such as “Where Are You?” (“Где ты?”) and “House on the Mountain” (“Дом на горе”), the latter one of Mikhail’s hits that then became one of her own. While she inherited many fans from her husband, the emotional depth of her original music, as well as her soulful take on Mikhail’s music soon meant that she stood on her own.

In 2006, she married her concert promoter, Tver-based entrepreneur Sergei Belousov. They would have one son together and later divorce in 2020.

In 2009, Irina released a joint album with Viktor Korolev, Bouquet of White Roses (Букет из белых роз), and the title track became her signature hit, with its lively beat and synth backtrack showcasing the heavy pop influence that exemplifies her personal sound.

Pop is also prominent on other hits such as 2017’s “Glass of Bacardi” (“Бокал ‘Бакарди’”), 2013’s “Little Keys” (“Ключики”), and 2010’s “I Will Read in Your Eyes” (“Я прочитаю в глазах твоих”). Her songs focus on themes of love, with the criminal and military themes found in Mikhail Krug’s music absent from Irina’s original work. Thus, Irina Krug is solidly in the “romance” subcategory of shanson. Some critics have claimed that she is only considered “shanson” because of her connections to her late husband. However, this criticism has not kept her from being successful and she has had new hits on Radio Shanson nearly every year that she has been active.

Since 2018, she has performed and sang duets with her son, Alexander Krug (who also legally changed his name). Alexander had gone on to release his own records and original music and competed in Star Factory, a televised pop music reality show that awards winners record contracts. He also sings in the shanson genre and has dedicated many of his songs to his late father.

In 2022, on the 20th anniversary of Mikhail Krug’s death, Irina released another album dedicated to her late husband: I Bear Your Last Name (Я ношу твою фамилию). Tracks like “Last Name” (“Фамилия”) are a bittersweet tale of losing a loved one and having to move on while also cherishing the memories made together.

Maksim Leonidov

(Максим Леонидов)

Bio by Josh Wilson and Julie Hersh

Maksim Leonidov is best known for leading the popular Soviet pop-rock band Secret (Секрет), he has also led a solo career in Israel and Russia that has included work in shanson.

Leonidov’s parents both worked in theater and music. He attended music school in St. Petersburg and then studied theater at university. While in university, in 1982, he became a founding member of the beat-quartet band Secret.

He left Secret in 1989 and emigrated to Israel. While there, he released two albums, one in Hebrew and a mini-album with four songs in Russian. Neither is available online.

He returned to Russia in 1996 and began performing with Secret again. He also began performing shanson, at first solo, with the release of the album Commander (Командир), which was heavily rock-and-jazz influenced. He then formed Hippoband to accompany him. Many albums with them are still released under his name, however.

Their first album together, Floating over the City (Проплывая над городом), contained his first post-Secret major hit, the upbeat, jazz-infused, lyrical “Vision” (“Видение“). That song won a Golden Gramophone award (one of Russia’s highest awards). Hippoband went on to release several more albums, including an album of military shanson called Let’s Have a Smoke! (Давай закурим!) and an album of jazz-arranged lyrical shanson oldies called Daddy’s Songs (Папины песни).

Leonidov also acts and writes musicals. He played the lead in an Elvis biopic, The King of Rock and Roll and a lead in a Russian-language production of The Producers. He also helped create a musical with other members of Secret called Fear Nothing, I’m with You (Ничего не бойся, я с тобой), based on 23 of the group’s hits. It became the highest grossing theatrical production in Russian history. Leonidov is thus an example of a full and rare crossover between rock, shanson, and musical theater.

You’ll Also Love

Polish Rock Under Communism: Resistance, Censorship, and Defiance

Poland under communism experienced censorship and state control of the music industry, but never as fully as in the USSR. Protests and worker uprisings, sometimes at great cost to demonstrators, kept authorities wary and forced them to permit more cultural expression than elsewhere in the Eastern Bloc. Officials, for their part, justified their relative leniency […]

Music To Fall For: The Soviet Rock Revolution

The USSR did its best to control culture and make it serve the needs of the state. However, culture, like life itself, finds a way of spreading, evolving, and surviving, often against all odds. Rock music had, by the 60s and 70s, become a cultural phenomenon in Europe and America and its spread to the […]

Żywiołak: Pagan Rock from Poland with a Modern Mindset

Żywiołak, initially formed in Warsaw in 2005, is a Polish folk rock band steeped in mythos. Its name references the Elemental, a magical being said to harness the power of nature in the form of air, fire, water, or earth. Their lyrics sing of epic battles (in Wojownik, or Warrior) and explore the traditions of […]

The Hu: Mongolian Folk Metal

It is not typical for a Mongolian Folk-Metal Band to take the world by storm, but that is exactly what the Ulaanbaatar-grown metal band The Hu has done. After forming in 2016, they gained global recognition in 2018, mostly through the power of word-of-mouth and YouTube. The Hu’s first two singles, “Yuve Yuve Yu” and […]

5 Bands Bringing Traditional Kazakh Style to Modern Rock

Here are five Kazakh bands working to bring traditional Kazakh instrumentation and musical styles into modern music. Roksonaki Seamless Kazakh Folk Rock Roksonaki is a Kazakh band that was formed in 2006. Its name means “lightning” in Kazakh, chosen to represent the band’s energetic and electrifying musical style. They are known for their unique fusion […]