The USSR did its best to control culture and make it serve the needs of the state. However, culture, like life itself, finds a way of spreading, evolving, and surviving, often against all odds. Rock music had, by the 60s and 70s, become a cultural phenomenon in Europe and America and its spread to the USSR eventually became an inevitability that the authorities were forced to accept and try to coopt rather than stamp out.

The authorities’ efforts were mixed. Rebelliousness has always been an integral element of rock culture and the artists who would become the founding fathers of Russian-language rock would find ways to express their adopted culture despite efforts to constrain them. Today, these musicians and their bands – Victor Tsoi of Kino, Boris Grebenshchikov of Aquarium, Yuri Shevchuk of DDT, Mike Naumov of Zoopark, and many others are regarded as giants of modern culture. Through humor, guile, and no small amount of guts, they introduced Soviet citizens to a new way of making music and a new way of looking at the world.

This resource covers a general short history of Soviet rock, with a particular focus on censorship issues. A handful of the USSR’s most popular, influential, and/or illustrative bands are then introduced in roughly chronological order based on the date the group formed. Some of these bands have histories that span many decades, but their Soviet histories will be our focus here. Band names have been translated or transcribed in the manner usually used by the band. Album and song names are given in both English and Russian, with YouTube links when available.

A Short History of Soviet Rock

History by Ryan Hardy, Katherine Weaver, and Josh Wilson

Leningrad, the once-and-current St. Petersburg, was built to be a “window on Europe,” and remained just that under the USSR. Its proximity to Finland allowed its residents to tune into Western radio stations, like BBC and Radio Svoboda Evropa. For young people, the music programs on these stations, typically aired after the news hours that attracted their parents and grandparents, offered a retreat from the USSR’s cultural isolation from the West.

Much like with bardic music, rock initially spread hand-to-hand through copies that enthusiasts made at home in a process often refered to as “magnitizdat.” This word essentially means “magnetic publishing” and referred to the cassette tapes that were used to make amateur recordings and copies of them. Sometimes music was recorded at home from radio programs. Sometimes it was copied from smuggled albums of British and American bands, such as The Beatles, The Rolling Stones, David Bowie, The Velvet Underground, Joy Division, and Sex Pistols. These copies would eventually make their way deep inside the USSR.

By the late 60s, knowledge of the latest trends in Western culture was becoming so pervasive that officials started looking for ways to give them official expression in the USSR. One early example of this was The Bremen Town Musicians (Бременские музыканты), an animated rock opera produced by Soyuzmultfilm, the USSR’s premier animation studio. The characters sang rock songs and even wore the latest Western fashions. The result was a film that either astounded or angered audiences who saw this as shockingly free innovation or as a dangerous cultural intrusion.

Around this time, Soviet citizens were also starting to make their own rock music, recording privately and giving small concerts in apartments, courtyards, street corners, and sometimes in cafes by invitation. Tours were even sometimes organized, relying on private residences or neutral and informal public spaces.

Artists generally maintained other jobs, however. Earning money independently, including from concerts or album sales, was a criminal offense that could incur prison time in the USSR. Many artists were students when the bands formed. Many worked in factories, as engineers, or, quite commonly, in theatres and film studios.

Official Rock Clubs and the Censorship Labyrinth

By the early 80’s, groups of counter-culture youth were gathering on the major streets of the USSR, sometimes calling themselves “music clubs.” They would play songs for each other and sometimes perform acts of hooliganism. In Leningrad, the authorities saw a need to contain the new movement under Party supervision and censorship. In 1981, the opening of the Leningrad Rock Club provided the growing underground rock scene with a performance hall and audiences with a coordinated viewing experience. Much like in a theater, audiences were initially expected to remain seated for a rock shows’ duration. However, this soon proved unenforceable, especially as many shows were allowed to become “standing room only.”

Bands auditioned for membership and to participate in official rock festivals. Clubs had boards and juries for contests. These oversight bodies consisted of other musicians and party representatives. Songs had to be cleared with party censors before performing and this often affected how songs were written.

In terms of censorship, there were no guidelines to follow and often artists were denounced in the USSR arbitrarily. For instance, an early song by the band Mashina Vremeni called “Blue Bird,” (“Синяя птица“) was denounced, in part, for being “depressive.” There were also no guidelines on how a band should be censored. In the case of Mashina Vremeni, official meetings were held in the Ministry of Culture and motions were made to take further action against the group. However, public backlash against the denunciation led, in the end, to nothing happening.

Often, when action was taken against a group, it happened with no clear ruling or explanation. Thus, one could not even rely on precedent. For instance, after the group Alyans was accused of being “too closely aligned with Western culture” and “lacking in ideas,” they soon found themselves removed from an ongoing tour, denied recording and performance space, and, in the end, the band broke up as members sought ways to be productive.

In neither of these cases were these bands denounced for political ideas expressed in their lyrics. Bands were often denounced for how their music sounded, rather than what they said. Thus, even apolitical bands placed themselves in danger just by being in the public eye.

Enforcement also changed over time. In the early 1980s, the state was more likely to prosecute such “infractions,” even when the songs did not express opposition to written communist ideals in their lyrics. By 1987, however, the overtly political band Televizor was able to sing songs like “A Fish Rots from the Head” (“Рыба гниёт с головой”). While this song only names “they” and “you” – it is an obvious denunciation of Communist violence and societal acquiescence. The name of the song, a well-known Russian proverb, even directly refers to folk wisdom that organizations turn corrupt when their leaders do.

Meanwhile, early censorship was not able to stamp out the songs that would, in fact, become political calls for change, such as “The Turn” by Mashina Vremeni or “I Want Change” by Kino. Mashina Vremeni has always been a politically conscious band and wrote “The Turn” as a resistance song. It is couched in abstracted poetry, however, so that only implores the listener to not fear the inevitable changes that come in life. Kino was a decidedly apolitical band and “I Want Change” was mostly a genuine introspection into wanting more out of life and needing to overcome the inertia that prevents us from making changes happen. Both songs still resonate as deeply political today.

Couching language in abstraction or even absurdism occasionally threw off the censors. Still others found that they could do this by dedicating potentially offensive songs to political struggles that the Soviet Union supported, such as the Nicaraguan Peoples’ Liberation Movement. This could make it appear as though the song was critiquing some other society.

Despite having to find workarounds to participate in the clubs, party backing opened access to official concerts and recording studios. Tickets for the club’s performances sold out quickly and attracted a wide range of young people. Fan clubs popped up as bands became more popular, and some shows became so desirable that one could turn a large profit by scalping tickets, although this was illegal. Many artists gained fame, yet few gained fortune, with most continuing to work day jobs.

Although its effectiveness of the club at containing rock is debatable, the Leningrad Rock Club proved a popular and profitable venture. It spawned other institutions like it such as the Moscow Rock Laboratory and the Sverdlovsk Rock Club.

Rock in the Late USSR and after the Fall

During the mid to late 1980s, administrative control over the official rock clubs began to decline, in part because controlling them was close to impossible, and in part because Perestroika was gaining force under Gorbachev and official policy was shifting to allow for more free expression. Groups previously denied membership to the Leningrad Rock Club, for instance, on grounds of “ideological uncertainty,” such as DDT and Televizor, were permitted to play.

Still, some musicians regretted their mainstream fame and prominence. To some, the Leningrad Rock Club was seen as a “soft” alternative to the Young Communist League that converted rebellious musicians into law-abiding citizens, while for others, institutional endorsement indicated the musicians were complacent with the status-quo, which undermined their perceived authenticity.

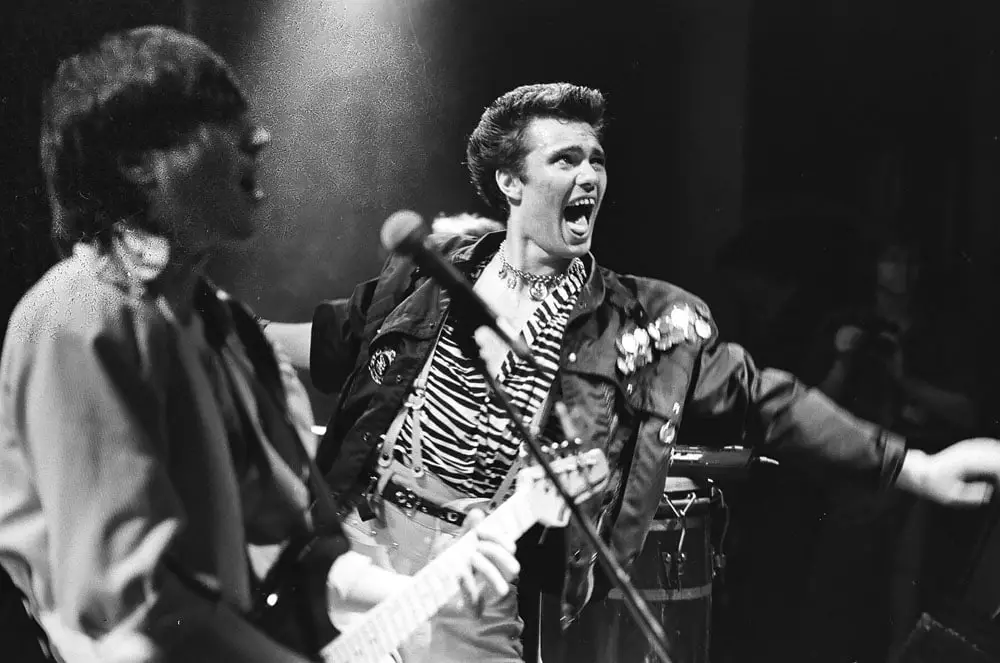

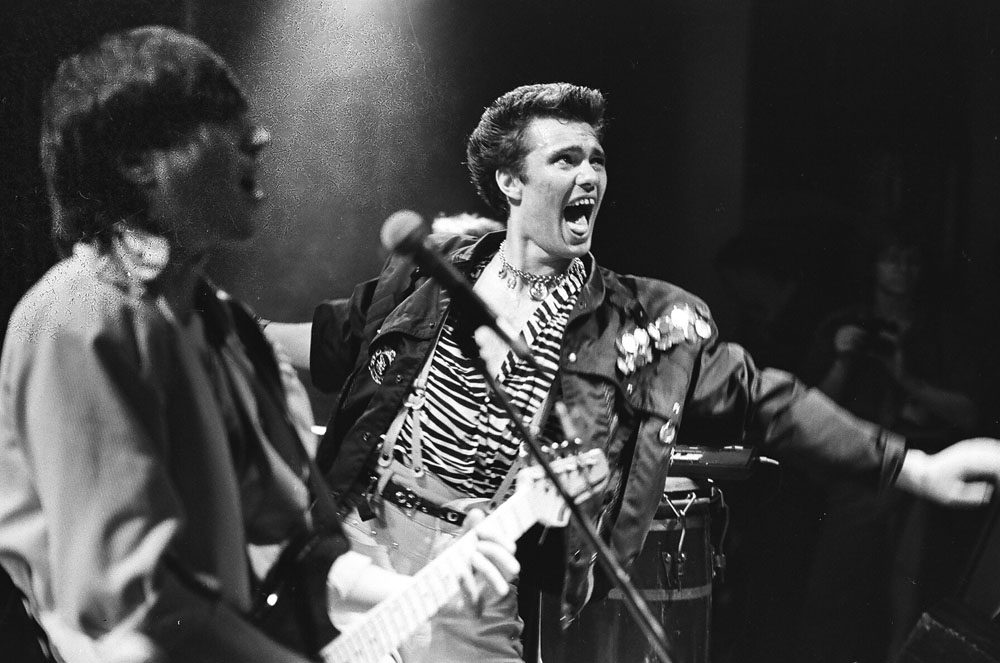

Above: AU plays at the Leningrad Rock Club, 1988

Perestroika presented new problems and opportunities for Soviet society. Drug abuse soared, and political and economic reforms proved disastrous. The Soviet rock community was also hit by the early deaths of some of its biggest names, such as Viktor Tsoi in August of 1990, followed by Maik Naumenko less than a year later. Tsoi in particular is still mourned and remembered to this day.

The rock clubs began to close with the collapse of the USSR and economic reforms of the 1990s. However, private clubs sprang up in their place, as did private record labels devoted to rock, punk, and other genres. The USSR’s major label, Melodiya, survived privatization and continues to operate today.

The Leningrad Rock Club played its final show in 1991, but reopened under new management in 2012. Musicians gather to celebrate its original founding each year. Leningrad rockers continue to hold a place in the world of Russian music, with many groups still performing today. Fans of Viktor Tsoi can still see cover bands perform his hits at Kamchatka, a museum and club established in the space where Tsoi worked as a maintenance man and gave performances.

For many of those who lived through the 1980s in the USSR, these bands serve as a soundtrack of the times, accompanying them through stagnation, glasnost, perestroika, hardship, and change. These bands provided an alternative to massified Soviet culture and often pushed back against party censorship. Whether it was through abstracted lyrics, the introduction of new musical styles, or a general sense of self-determination and confidence among the musicians performing, Leningrad rockers altered the perception of what was deemed socially acceptable and left a lasting imprint on post-Soviet culture and politics.

Mashina Vremeni and Andrei Makarevich

Машина времени и Андрей Макаревич

Intro by Zachary Hicks and Josh Wilson

Mashina Vremeni (Машина Времени, meaning “Time Machine” in Russian) is one of the most influential and enduring rock bands in Russian history, widely credited with laying the groundwork for Soviet rock music. The band was formed in 1969 in Moscow by Andrei Makarevich, a young musician heavily influenced by Western rock bands like The Beatles, Pink Floyd, and The Rolling Stones. Initially, the band was a loose collective of Makarevich’s medical school friends. Their first album, a bootleg titled and recorded in English as Time Machines. Only a few songs, like “This Happened to Me” are available online. By 1971, Makarevich established a more consistent lineup and began performing in Russian under the name Mashina Vremeni. Their early music blended rock, blues, and folk influences.

Throughout most of their early existence, Mashina Vremeni operated almost entirely outside official Soviet music institutions, relying instead on magnitizdat (self-distributed tape recordings) to circulate their music. Their lyrics, all written by Makarevich, are not overtly political, but often explored themes that could be considered subversive such as personal freedom, disillusionment, and existential longing.

In 1975, they began to make some inroads into official entertainment structures. They were invited to participate on national TV on the popular Musical Kiosk program. They were eventually cut from the broadcast, but the experience gave them temporary access to a professional studio and they were able to quickly record a high-quality second album. Appropriately titled Recording of Mashina Vremeni for the Musical Kiosk Program (Запись «Машины времени» для программы «Музыкальный киоск»), and featuring seven original Russian-language songs, it was then distributed via unofficial channels.

In 1976 and 1977, the band was invited to play at the Youth Song Festival in Tallinn, Estonia, to some acclaim.

In 1978, the group met Ovanes Melik-Pashayev, a physics professor from Moscow State University who proved remarkably adept at organizing illegal, for-profit concerts. Soon the group was earning about five times the average Soviet salary. That year, the band also started performing Little Prince (Маленький Принц), a theatrical piece presenting songs interspersed in the read text of the famous children’s story of the same name. This effort featured several of their most enduring hits, including “The Turn” (“Поворот“) which became a generational anthem for demanding change that is still used by the Russia’s political opposition.

By the end of the 70’s, they were being closely watched by the authorities for their concert activities and a “curator” from the Communist Party had been specifically assigned to them. It was eventually decided to attach them to the relatively unknown Moscow Regional Touring Comedy Theater. Instead of being shunted out of the way, the group found that this official appointment gave them still greater access to official channels, legitimized their concerts as being given as part of the theater. The theater, for its part, now sold far more tickets with Mashina Vremeni loudly advertised on the playbill.

In 1979, Mashina Vremeni’s songs found their way onto Soviet radio, with “The Turn” (“Поворот“) sitting at number one for seven months straight. The group performed at the Tbilisi Rock Festival in 1980, one of the first state-approved rock festivals in the Soviet Union. Their performance was widely praised, and Mashina Vremeni won the festival’s Grand Prix and had their song, with other festival winners, officially released on a vinyl record.

More popular then ever, the group applied to reinstate their production of Little Prince, this time at the large, central Variety Theater. The application was denied on command of the Moscow Communist Party and the group suddenly found themselves unable to perform anywhere in Moscow until 1986. They went on tour to Leningrad, and then found that the rest of the USSR was also still open to them. They received work writing and performing songs for Soviet movies. One of these, Soul (Душа), released in 1981, became one of the highest grossing Soviet films.

1982 proved turbulent for the group. Half their members as well as Melik-Pashayev left to form the group Voskreseniye. Ultra-conservative premier Yuri Andropov also came to power that year and tried to wipe out rock music. Mashina Vremeni and its song “Blue Bird,” (“Синяя птица“) was denounced in the press for being “ideologically unsound.” However, the band received a nationwide outpouring of support, up to 250,000 letters from the public, against these denunciations, which actually increased their popularity in the end and rendered efforts to silence them useless. It likely helped as well that they were major headliners and profit-generators for RosConcert, the official Soviet concert venue, and were still proving very valuable to the Soviet film industry.

In 1985, Gorbachev’s perestroika began, and suddenly all doors were open to the group. A movie, From the Top (Начни сначала), starring Andrei Makarevich and loosely based on the group’s overcoming their recent denunciation is produced. The group suddenly appears on TV regularly. In 1986, they not only regain access to Moscow, but are also signed by Melodiya, the major Soviet record producer, are invited to festivals, and received the rare permission to go on an international tour.

In the last years of the USSR, the group released a number of albums, including Rivers and Bridges (Реки и мости), In the Circle of Light (В круге света). The group celebrated their 20th anniversary in one of Moscow’s largest stadiums, with nearly everyone who had ever played in the band reuniting, and multiple other major singers making guest appearances. Makarevich emerged as a moral authority during the turbulent period of the Soviet Union’s collapse.

After the fall of the USSR, Mashina Vremeni remained active, releasing new music and re-recording and remastering old music. They retained their appeal across generations and gained access to global stages and continued to address social and political issues. Makarevich remained outspoken politically through the Yeltsin and Putin eras, which occasionally caused the band’s concerts to be canceled or disrupted by pro-Kremlin groups. That said, the group’s last release of new music was in 2020 and their website has not been updated since 2021.

Makarevich, as an individual artist, has maintained his personal website, and wrote anti-war songs as an individual. He and his wife relocated to Israel in 2022. Other band members, such as Evgenii Margulis, have not made definitive statements about the conflict and have remained active inside Russia as individual artists.

Aquarium and Boris Grebenshchikov

Аквариум и Борис Гребенщиков

Intro by Zachary Hicks and Josh Wilson

Aquarium (Аквариум) was formed in 1972 in Leningrad (now St. Petersburg) by then-19-year-old Boris Grebenshchikov, a university student deeply influenced by Russian bards and Western rock bands such as Bob Dylan, David Bowie, and Jethro Tull. Together with Anatoly Gunitsky, a poet and drummer, Grebenshchikov initially founded the group as a small acoustic folk rock ensemble. However, it soon expanded to incorporate electric and electronic instruments, developing a sound that fused psychedelic and folk rock as well reggae influences together with traditions of mystical and classical Russian lyricism.

Over the more than five decades that the band has been making music, Grebenshchikov and Gunitsky have been the only constant members. Grebenschikov is the undisputed front man, both the lead singer and artistic driver.

Within a few years of the band’s formation, Grebenshchikov was accepted into the prestigious Leningrad State University. During this time, Grebenshchikov’s musical activity began to take precedence over his studies, as he avidly consumed music by the Beatles, Bob Dylan, Cat Stevens, and others. During these early years, Aquarium led a counterculture lifestyle: playing in apartments, hitchhiking to out-of-town gigs, and so on. Though they did not have access to quality recording studios, Grebenshchikov and Aquarium managed to release a few DIY albums during this time. In 1976 Grebenshchikov also recorded his first solo album, On the Other Side of the Mirror Glass (C той стороны зеркального стекла).

In 1980, Aquarium was chosen to participate in the Tbilisi Rock Festival, one of the first state-sanctioned rock festivals in the USSR. Although Aquarium’s performance, characterized by theatrical stage antics, confused the festival’s judges, the audience responded enthusiastically. Nevertheless, Aquarium was denounced by Soviet officials, Grebenschikov was fired from his day job and expelled from the Komsomol. The band could not perform in public venues for a time.

Despite the troubles caused by the festival, Aquarium’s underground popularity continued to grow. In 1981, they were able to release their first studio album, The Blue Album (Синий альбом) and became founding members of The Leningrad Rock Club. The Blue Album is generally regarded as the USSR’s first studio-produced full-length rock album (although it was still unofficial and “underground”).

Aquarium has released a steady supply of new material ever since. In 1984, they released Day of Silver (День Серебра), their fifth full studio album, and what Grebenschikov considered to be best the album released in the 1980s by the group. In 1986, they were featured as one of four Soviet bands on Red Wave a double album released in the US by independent producer Joanna Stingray. Stingray mailed a copy to Gorbachev, who then personally questioned why a major Soviet studio had not yet released a rock album. Melodiya, the major state record company, was given orders to sign Aquarium immediately.

Melodiya recorded and released the White Album (Белый Альбом) in 1987, one of the first rock albums released as an officially-pressed vinyl record in the USSR. This was a compilation of music from Day of Silver and Children of December (Дети Декабря), both albums that the group had already released on tape. The next year, Equinox (Равноденствие) was released, the first fully official new album for the group. However, writing and recording for Melodiya proved tedious and bureaucratic. Grebenshchikov was displeased with the process and the result.

At this time, the group was also composing and recording soundtracks for movies and serials, which were increasingly using rock music. An early effort was Assa (Асса). Other soundtracks were produced by Aquarium under the name “The Russian-Abyssinian Orchestra” (Русско-абиссинский оркестр).

Despite their success – or perhaps because of it – many members of Aquarium began to leave for other bands or attempted to start their own. Grebenshchikov himself used this time to try to break into the international music scene, recording Radio Silence, an album recorded almost entirely in English and recorded in the US, Canada, and UK, produced by David Stewart of the Eurythmics. This created tension within the group as it often meant Aquarium’s front man was absent for concert dates elsewhere.

The original Aquarium officially broke up in 1991. Grebenshchikov formed BG-Band, which was supposed to be a “reincarnation” of Aquarium and were known as a “dark folk” group. They released one album, The Russian Album (Русский альбом), and toured for a year before breaking up when Aquarium 2.0 formed. Aquarium is now in its 4.0 incarnation and still releasing albums regularly. Grebenshchikov also maintains a number of solo and collaboration projects. He also had a long-running weekly radio show on Radio Rossii.

As a lyricist, Grebenshchikov has an eclectic style that combines themes of Buddhism, Russian Orthodoxy, alcohol consumption, technology, and so on. Grebenshchikov has written more than 500 songs and recorded more than two dozen albums. He has always been outspoken about certain issues and, after speaking out against the war in Ukraine in early 2022, he was declared a “foreign agent,” which would require him to apply this term as a warning to any public performance or publication in Russia. Today, he still officially lives in Russia but has only toured abroad. .

He is a long-time Buddhist and also known as a translator of Tibetan Buddhist books into Russian.

Auktyon and Leonid Fedorov

АукцЫон и Леонид Фёдоров

Intro by Chris Wehberg

Auktyon (stylized as АукцЫон) is a long-lived Russian avant-garde rock band formed in 1978 by Leonid Fedorov in Leningrad. Fedorov became its front man, lead vocalist, and key creative force – although much of the band’s success can be credited to its freewheeling collective and chaotic creativity. Fedorov’s distinct vocal style, unconventional guitar playing, and poetic, sometimes cryptic lyrics helped shape Auktyon‘s identity. He is known for using unusual meters. This is seen in the 2002 hit “Winter” (“Зима”), which is sung in 5/4 irregular time meter, an uncommon choice for the rock genre, but one that works well for the complex lyrics of the song. Auktyon’s theatrical and unpredictable performances and known for featuring free-form musical arrangements.

The band was originally a trio of Fedorov and his classmates Dmitry Zaichenko and Alexei Vikhrev. Today, there are nine regular members in the band, including Lenya Fedorov (vocals, guitar), Viktor Bondarik (bass), Kolya Rubanov (saxophone), Misha Kolovsky (tuba), Dima Ozersky (keyboards), Vladimir Volkov (double bass), Yuri Parfenov (trumpet), Boris Shaveynikov (drums), and Oleg Garkusha (everything else). The composition of the band has changed noticeably in the past few decades, and most of the members are involved in other artistic projects.

Although formed in 1978, Auktyon was largely unknown until 1983 when it was accepted as a member of the Leningrad Rock club. Previously known as Параграф (Paragraph), Фаэтон (Phaeton), and other names, their acceptance to the rock club forced the group to solidify “АукцЫон” as their stage name. They chose it by flipping through a dictionary and deciding that “Аукцион” (Auction) had a nice ring. When band member Boris Shaveynikov wrote it down, however, he misspelled it, using an “ы” in place of the phonetically similar “и.” The band decided to run with it, however, and even capitalized the “Ы” (which very rarely begins words in Russian and therefore is rarely seen capitalized at all, making it particularly striking). In another twist, they made the preferred English version of their name “Auktyon,” which is not a proper transliteration. “Auktyon” mis-renders the middle letter, a proper rendering of which would make the name “Auktsyon.”

Their first album Return to Sorrento (Вернись в Сорренто) was an immediate hit in 1986, with popular songs such as “Money is Paper” (“Деньги – это бумага”) and “Wonderful Evening” (“Чудный вечер”).

Auktyon is hard to pin down in terms of genre, as they take inspiration from ska, swing, reggae, new wave, jazz, music from North Africa and the Middle East, as well as pop and psychedelic music of the 60s. Auktyon also makes all their music freely available. The band makes its money from concerts and regularly gives tours abroad.

In 1989, the band experienced a major scandal in the Soviet press for their behavior on tour in France. Former member Vladimir Veselkin (active 1987-1992) came under fire for imitating a striptease to the band’s song “Nepman,” (“Нэпман”) even though the act was not revealing in any nature. Multiple newspapers called the group “tasteless” and “vulgar.” The band was not phased, and Veselkin even repeated the performance at a later show. Several audience members accused Auktyon of “discrediting Soviet rock.”

Over the course of their 43 years together, the band has experienced many creative changes. In 1991, with the fall of the USSR, AuktYon’s style became darker and more improvisational – somewhat appropriate as the country fell apart around them. One of their most popular albums to date is Bird (Птица), released in 1993. This is largely thanks to the song “Road” (“Дорога”) which remains one of their all-time classics and was featured on the soundtrack of the cult film Brother 2 (Брат 2) (2000). After the release of Bird (Птица), the band struggled creatively, fearing that they could not recreate the success of that last album.

However, AuktYon is, in part, likable, because they openly embrace their fallibility. Even personal vices are publicly shared, like when, in 1996, Oleg Garkusha underwent treatment for alcoholism in the United States and eventually quit drinking. The constant influx of new members and collaboration with other creatives, such as Хвост (Alexey Khvostenko), Yegor Letov, and Svyatoslav Kurashov, is also a notable factor towards their success, as the band is constantly exploring new inspiration from fresh minds.

The band was eventually able to overcome their creative block in part by collaborating in 2007 with American musicians Mark Ribot and John Medeschi on their jazzy album Girls Sing (Девушки поют). In 2013, the band went on a 30th anniversary tour which also featured a 20th anniversary concert for the album Bird (Птица).

Their latest album Dreams (Мечты) was released in 2020. The album blends jazz with grungy rock, primal beats, and often bard-like lyrics giving it an experimental but also highly familiar feel. In summer 2021, Auktyon is went on tour to promote that album. Auktyon has released 11 studio albums in total, including as recently as 2020, while also winning awards, attending festivals, filming movies, and going on tour.

Piknik and Edmund Shklyarsky

Пикник и Эдмунд Шклярский

Intro by Zachary Hicks

Piknik (Пикник, meaning “picnic” in Russian) is a long-running Russian rock band. Headed by vocalist/guitarist Edmund Shklyarsky (Эдмунд Шклярский), Piknik was formed in Leningrad in 1978, heavily influenced by British rock groups like Led Zeppelin and Jethro Tull. Over the years, however, Piknik has developed their own unique sound that combines symphonic and folk instruments with a dark, post-punk or even a gothic rock feel. The band draws inspiration from world music, literature, mythology, and more, and has stayed largely apolitical throughout its existence. They are known especially for highly theatrical performances and for incorporating exotic folk instruments from around the world to their music.

Piknik’s original members were a group of friends from Leningrad State Polytechnic University. The name “Piknik” comes from the Strugatsky brothers’ classic 1971 Soviet sci-fi novel Roadside Picnic (Пикник на обочине), reflecting the often surreal lyrics of the group. Shklyarsky joined the group in 1981, and has since been the band’s only constant member across its 30+ year career. He made his debut performance at the famous Leningrad Rock Club. Piknik released their debut album, Smoke (Дым), the following year and started to draw a larger following.

From 1984 to 1986 Piknik did not have a consistent lineup, and recorded their next two albums using session musicians to fill in the gaps. In 1986, however, Piknik embarked on their first tour, to Donetsk and Tallinn, with a full lineup that would remain more or less consistent for several years. In 1988, Piknik released their classic fourth album entitled Hailing from Nowhere (Родом ниоткуда). During the next few years they played several large festivals in Russia, the Baltics and, notably, in Osaka, Japan.

During the late 1980s and 1990s, Piknik continued to release albums, eventually developing a highly original sound that seems equally conversant with classic rock and post-punk. Notable releases from the 90s include the albums Vampire Songs (Вампирские песни), Ginseng (Жень-шень), and the experimental electronic album Drink Electricity (Пить электричество).

The early 2000s saw the single “Silver!” (“Серебра!”) stay high on the Hit Parade charts for several months. In 2004 Piknik put out a 20-year anniversary re-release of the album Dance of the Wolf (Танец волка). The following year, Piknik embarked a massive tour, and their biggest show (in St. Petersburg) was released on DVD.

To this day, Piknik has maintained a solid following, continued to release a slew of albums and singles (generally within three years of each other), and gone on several large tours in Russia and abroad.

Automatic Pleasurers and Andrey “Pig” Panov

Автоматические удовлетворители и Андрей “Свин” Панов

Intro by Zachary Hicks and Ryan Hardy

Automatic Pleasurers (Автоматические удовлетворители) was a seminal Russian punk rock band. The group had a fluid membership, serving more as a music club with dozens of musicians than a band in the traditional sense. Several prominent Russian rockers got their start playing with Automatic Pleasurers, including legendary Kino front man Viktor Tsoi, Mike Naumenko of Zoopark, and Tequilajazzz’s Yevgeny Fyodorov.

Andrey Panov, known as “Pig” (“Свин”) and widely regarded as “The Father of Russian Punk,” started the group in Leningrad in 1979. Panov was taken with the punk aesthetics of The Sex Pistols after reading a Soviet newspaper article criticizing that group, even though he had barely heard their music. Panov became an avid follower of Western punk trends and adopted its style and ideology, like the “do-it-yourself” mentality and anti-conformism, not only in his music but in his daily life. Panov and his friends could often be found around Leningrad, engaged in hooliganism that verged on performance art. For instances, they played dead in a city park for several hours or shoveled snow naked until authorities were called. Often performing in venues off the beaten path and on shoestring budgets, Panov showed that one didn’t need expensive equipment or decadent performance spaces to draw a crowd. More importantly, he showed that one could perform independent of state support while publicly living outside of societal norms.

Their first album, Fools and Guest Artists (Дураки и гастроли) from 1980 has no surviving copies. Their second was first released in 1983 and then again with an additional track in 1985 under the title Terry – Cherry – Pig (Терри – Черри – Свин). Although the band was raucous and very anti-establishment, they were able to join the Leningrad Rock Club in 1987. That same year, they recorded another album, Reagan is a Provocateur (Рейган — провокатор).

In 1992, the group gave a scandalous television performance on Program A (Программа А), which was something of a watershed moment for post-Soviet punk music. The broadcast marked one of the first times that raw, unfiltered punk energy—complete with aggressive lyrics and provocative stage antics was allowed to be seen on national television.

1992 also saw the release of the group’s only studio album produced and released by an actual label. Drink with Us! (Пейте с нами) was also rereleased as a double album with additional material from Olesya Troyanskaya. The album from the Automatic Pleasurers included one of the group’s best known songs, “Cucumber Lotion,” (“Огуречный лосьон“). The lotion is a symbol of the all-to-common shortages that faced Russia’s economy under Perestroika and just after independence: a man waiting in line for wine at a grocery store who, upon arrival at the entrance, finds that the store is out of stock. He asks a nightingale, which is usually a source of wisdom in Russian folktales, where the wine went and is told that “In the department store, they’re selling cucumber lotion.” After the man slaps the bird against a road sign, he stomps off to buy the lotion, declaring his exaggerated love for the only thing he can apparently buy in his society. For young people living through a tremendous and seemingly foreign shift towards democracy and capitalism, the song’s anecdotal slapstick humor provided a friendly voice of understanding to an unfamiliar post-Soviet life.

In the mid-90s, Panov began experimenting with more complex collaborative ventures. The band split into two different groups: the original band, which continued to play punk rock, and Arkestra AU (Аркестр АУ; an intentional misspelling of “Оркестр,” or Orchestra), which included more professional-sounding musicians and played in an experimental style bordering on disco. Arkestra AU only created one album, With Special Cynicism (С особым цинизмом). Panov also spent 1998 experimenting with a band called RockNRoll City, the result was the album The Feast of Disobedience, or the Last Day of Pompey (Праздник непослушания или последний день Помпея).

Over the course of their career, the majority of important underground Leningrad and Petersburg musicians collaborated at some point with The Automatic Pleasurers. The group disbanded in August 1998 when Panov died of an abdominal disorder.

Voskreseniye and Aleksey Romanov

Воскресение и Алексей Романов

Intro by Zachary Hicks and Josh Wilson

Voskreseniye (Воскресение) is a Russian rock group which has existed in two distinct incarnations. The first lasted from 1979 to 1982; the second, after a long hiatus, started in 1994 and continues to the present day, although nearly all their original songs were released in the first iteration. Voskreseniye’s sound ranges from rhythm-and-blues to blues to psychedelic rock. Its name translates to “Sunday,” “Resurrection,” or “Rising.”

Voskreseniye started in spring of 1979 after drummer Sergei Kavagoe and bassist Evgenii Margulis left Mashina Vremeni. They approached Aleksey Romanov, who had been heading a group called Kuznetsov Bridge (Кузнецовский мост) and proposed forming a new band. Alexey Makarevich, who played lead guitar for Kuznetsov Bridge was also invited. Wanting to get material circulating quickly, Voskreseniye’s first releases were actually covers of Mashina Vremeni and Kuznetsov Bridge songs. As the USSR had no copywrite laws, this was not a problem. Voskreseniye found its way onto the radio in time for the 1980 Olympics. “Who is to Blame?” (“Кто виноват“), originally a Kuznetsov Bridge song, became an instant international hit for Voskreseniye.

Two albums – Voskreseniye 1 (Воскресение 1) and Voskreseniye 2 (Воскресение 2) were quickly released in 1980 and 1982. Then, in 1983, Alexey Romanov and his sound engineer were arrested and charged with entrepreneurship, a crime in the USSR, for receiving money at private concerts. Romanov was sentenced to three-and-a-half-years’ probation and his most valuable possessions – his bank account and guitar – were confiscated. The sound engineer received three years in prison. After the sentencing, the band was no longer invited to perform anywhere. Voskreseniye broke up in 1984.

Aleksey Romanov moved on to other projects, including joining the group SV (СВ). In 1989, Voskreseniye was allowed to perform a 10th anniversary show. They reunited again in 1992 and officially reassembled in 1994. Since that time, they have released remastered versions of their first two albums and a collection of re-recorded hits called All Over Again (Всё сначала). In 2003, they released a new studio album Taking Your Time (Не торопясь).

They have kept busy with concerts, live albums, and collaborative projects with orchestras and other bands. Voskreseniye continues to play to this day.

DDT and Yuri Shevchuk

ДДТ и Юрий Шевчук

Intro by Julie Hersh

DDT (ДДТ) is a Russian rock band founded in Ufa in 1980 by Yuri Shevchuk, a young poet and songwriter with a background in fine arts. He quickly became known for his poetic lyrics, sharp political commentary, and deeply humanistic outlook. He openly addresses personal alienation, political repression, war, and social injustice. The band’s name, DDT, was taken from the powerful chemical pesticide of the same name, a reference that Shevchuk later claimed was meant to evoke a sense of disruption and social “cleansing.” Shevchuk earliest influences were the Soviet bards, especially Vladimir Vysotsky and Alexander Galich, as well as Russian Silver Age poets such as Osip Mandelstam and Evgenii Yesenin.

In 1981, they released their first album, DDT-1 (ДДТ-1), a non-studio recording which mixed highly performative bardic tradition with psychedelic rock. Their first big breakthrough came in 1983 when “Don’t Shoot!” (“Не стреляй!”) unexpectedly won first prize at the Tbilisi Rock Festival. Taken from their second album, Pig on a Rainbow (Свинья на радуге), released in 1982, the song was a thinly veiled protest against the Soviet-Afghan War and immediately drew the attention of Soviet censors, who began watching the band closely.

DDT’s next album, Compromise (Компромисс) took them to new heights in 1983. However, their performance at the official Rock for Peace Festival in Moscow was cut from the television broadcast and the DDT was banned from having their music exported abroad. With so much attention from the authorities, the band soon found recording difficult and moved to Leningrad in search of better opportunities. There, they were able participate in the Leningrad Rock Club and even appeared on TV again, performing “Rain” (“Дождь“), one of their best-known hits.

DDT recorded several more albums over the next decade, though the band’s composition kept changing. Shevchuk has been the only constant member. After the fall of the USSR, they gained even more popularity and continued to record, including the highly popular The Actress Spring (Актриса Весна) in 1992. Another major album was the 1998 World Number Zero (Мир номер ноль), which was a turn toward industrial / electronic music, in contrast to their earlier classic rock.

Since the fall of the USSR, Shevchuk has also become a public face of Russia’s political opposition. He traveled to Chechnya during the 1994 Chechen War to perform concerts for peace. He attends and performs at opposition rallies and has helped campaign for the preservation of historical buildings. He has also publicly clashed with Russian President Vladimir Putin on several occasions. In May of 2022, he made critical comments about the war in Ukraine at a concert. He was charged with Discrediting the Russian Army and fined 50,000 rubles. While he is still touring abroad and still officially lives in St. Petersburg, he has declared that he will no longer perform inside Russia, saying that “the conditions that were set for us in order to perform… I cannot agree to this agreement, I cannot sign it in blood, no. I am not Faust.”

Zoopark and Mike Naumenko

Зоопарк и Майк Науменко

Intro by Morgan Henson and Josh Wilson

Zoopark (Зоопарк) was formed in 1980 in Leningrad by Mike Naumenko, a charismatic songwriter and vocalist who had been deeply influenced by Western rock, particularly Bob Dylan, Lou Reed, and The Rolling Stones. He was known for his blues-rock sound and rebellious lyrics that reflected themes of urban life and youthful disillusionment. The name was meant as a pointed jab at state censorship, which Naumenko felt kept art and artists visible, but also visibly in cages.

Naumenko was born in Leningrad and attended a school with an intensive English-language program where he began to develop an interest in English-to-Russian translation. At the age of 8, he heard The Beatles for the first time and became interested in studying music. He learned to play the guitar and, by 15, was writing songs, at first in English. He switched to writing in Russian a couple of years later when he started composing songs with his friend, Boris Grebenshchikov, who would later form the band Aquarium.

After finishing school, Naumenko followed the advice of his father and enrolled in the St. Petersburg State University of Architecture and Civil Engineering, but during his fourth year of university he lost interest and dropped out. He began to seriously focus on his music while working as a sound engineer and watchman for the Bolshoi Puppet Theatre (Большой театр кукол).

Naumenko began his music career playing in obscure and oddly-named Leningrad bands such as Union of Lovers of Rock Music (Союз любителей музыки рок) and The Vocal-instrumental Band Named in Honor of Chuck Berry (Вокально-инструментальная группировка им. Чака Берри). These groups played classic rock. In the latter half of the 1970s, Naumenko joined Aquarium as a guitarist.

With the help of Boris Grebenshchikov and Vyzcheslav Zorin (leader and guitarist of Aquarium), Naumenko released his first solo album Sweet N and Others (Сладкая N и другие) in 1980, which channeled considerable inspiration from America’s 1950s and 1960s. In 1981, Naumenko organized the rock band Zoopark where he was a lead vocalist and art director. For the following three years, the band travelled between Moscow and Leningrad playing Naumenko’s music.

From the start, Zoopark operated on the fringes of the official Soviet music scene. Like other underground rock bands, they were associated with the Leningrad Rock Club and participated at many of the club’s annual rock festivals. In 1983, they released their first official album, Country Town N (Уездный город N). Country Town N is a common name used in Russian literature to refer to a fictional town that could be located anywhere in Russia’s provinces. A particularly well known example lies in Nikolai Gogol’s The Inspector General, which specifically skewered corruption. The album included “Blues de Moscou” (“Блюз-де-Москва“), which was already a cult favorite from their performances and remains one of their enduring hits.

Naumenko performed most of his songs in recitative style which lead to many comparisons to Bob Dylan and Lou Reed. In fact, many of his songs were taken from classic US artists. For example, Naumenko’s “Call Me Early in the Morning” (“Позвони мне рано утром“) is derived in lyrics and melody from Bob Dylan’s “Meet Me in the Morning.” There were no plagiarism laws in the Soviet Union, so this was generally not seen as a problem at the time.

The years that Yuri Andropov spent as Communist General Secretary (1982-1984) were not easy for Soviet artists. Andropov considered Western culture to be dangerous and anti-Soviet and, while the clubs remained active, rock artists were watched carefully for any infractions that could be prosecuted. This time hit Naumenko and Zoopark particularly hard, as he watched his guitar player be imprisoned for marijuana possession and his drummer arbitrarily exiled to Petrozavodsk, never to return to music.

Naumenko and his remaining guitar player worked with friends from Aquarium to record a second album, White Stripe (Белая полоса), a reference to the Russian proverb that “life is striped” (жизнь полосатая), meaning that one must take the good times with the bad. This album had another of their enduring hits, “Boogie Woogie Every Day” (“Буги вуги каждый день“). However, during this time, the band kept public appearances few.

With glasnost, the band re-emerged with a new permanent line up and began actively performing. They were perhaps never more popular and successful. However, Naumenko was sliding into depression and his problems with alcohol were becoming more pronounced. He no longer wrote new music. In 1990, a short film about the band’s history was produced, called Boogie Woogie Every Day (Буги-вуги каждый день). The film is dark, juxtaposing the band’s carefree 50s sound against heavily shadowed images and foreboding background noise, giving the impression that the music had perhaps not been created or performed during happy times.

However, the film inspired new music from the group, which was released together with new recordings of old hits as a new album in 1991 called simply Music for the Film (Музыка для фильма).

By the end of the 1980s, however, Naumenko had lost most of his control over his left hand and his speech had deteriorated, making it extremely difficult for him to perform. His wife left him at about this time as well. On August 15, Naumenko played for the last time in his apartment for a small group of friends and, on August 27, 1991, at the age of just 36, Naumenko died from a cerebral hemorrhage in his apartment in Leningrad. Zoopark never played again, although a post-humous album, Illusions (Иллюзии), which included many previously unreleased and experimental recordings.

Naumenko is buried in Volkovo Cemetery, alongside many of Russia’s cultural greats, in St. Petersburg, Russia.

Kino and Viktor Tsoi

Кино и Виктор Цой

Intro by Zachary Hicks

Kino (Кино, meaning “movies” in Russian) was formed by the legendary Viktor Tsoi in 1981. Tsoi usually listed Russian groups and singers as his early inspirations – especially Vladimir Vysotsky and Mikhail Boyarsky and other contemporary Soviet rock bands. Later, he became a fan of Western bands R.E.M., The Cure, The Smiths, and Joy Division. Kino itself has heavily influenced Soviet and Russian rock, punk, and alternative music.

Kino was one of the most popular Soviet rock groups of the 1980s and 1990s and remains one of the most timeless. Bardic influence is heavy in their songs with stripped-down instrumentation allowing Tsoi’s voice and lyrics, poetic yet accessible, to dominate the songs. Those songs centered on perennial themes of love, life, and freedom. They discussed everyday working-class life, being down-and-out, wanting change, trying to be happy, and yet largely avoided being overly political, instead focusing on introspective emotions. Tsoi himself was known for being sensitive and often playful, but also for the intense, genuine emotion he displayed in his writing and performace.

The band was first known as “Garin and the Hyperboloids” (Гарин и гиперболоиды) after an Aleksei Tolstoy novel. The name was changed to “Kino” when they joined the Leningrad Rock Club. The new name was chosen for being poetically concise, having a postive air, and being easy to pronounce in several languages, perhaps showing Tsoi’s artistic ambitions.

In 1982, the group released its first album, 45, which used a drum machine instead of a live drummer (at this time Kino consisted only of Tsoi and his close friend Aleksei Rybin) and has a lo-fi style due to poor recording conditions common to self-produced music in the USSR at the time. The album was not much of a success on release, but retains cult status today. The next few years of Kino were marked by personal and creative tensions between Tsoi and Rybin, culminating in the latter’s leaving the band in 1983.

Kino’s first big success came with their second album in 1984, the much more polished The Head of Kamchatka (Начальник Камчатки), featuring guitar, bass, cello, saxophone, synthesizers, and other instruments. Despite having much more depth, it kept the stripped-down quality the band was always known for. The name came from Viktor Tsoi’s day job as a maintenance man in an apartment building called Kamchatka. Soon after, Kino opened for the already-famous Aquarium in a concert just outside Moscow, and shot to popularity.

As the USSR began to open up, the group gained international attention. The 1985 release of Night (Ночь) sold more than two million copies. The group was featured that same year in the American release of Red Wave: 4 Underground Bands from the Soviet Union, the first Soviet rock release in the United States.

In 1988, Blood Type (Группа крови) was released. This album is considered one of the best in Russian rock. Also in 1988, Tsoi starred in a movie called The Needle (Игла). Tsoi’s performance was critically acclaimed and Kino provided an original soundtrack to the movie.

In 1990, at the height of their popularity, Tsoi was tragically killed in a car crash outside Riga. Only 28 years old, Tsoi’s death was a tragedy for his generation. His bandmates completed and released what had been a partially recorded album before Tsoi’s death. Untitled and released with a plain, black cover, it is known as The Black Album (Черный альбом), a sign of mourning for Tsoi. The band broke up after its release.

Shortly after Tsoi’s death, the words “Tsoi Lives!” (“Цой жив!”) were spray-painted on a wall near Moscow’s Old Arbat Street. Others soon added lyrics from Tsoi, portraits of Tsoi, and more. Graffiti to this day is added constantly to what is now known as “Tsoi’s Wall.” The place is a frequent hangout for Moscow’s punks and rockers. In Kamchatka, the building where he once lived a worked, a museum and club has been established that is dedicated entirely to his work and to bands covering his songs.

The remaining members of Kino reunited briefly in 2012 in honor of what would have been Tsoi’s 50th birthday. They completed a single track: “Ataman” (“Атаман“). The title is a honorific given to leaders of steppe nomadic groups and Cossacks. The song was supposed to be included in Черный альбом, but had been left out as the vocal recording was considered too low-quality. Thanks to advances in technology, the group was able to remaster it for release.

Alyans and Igor Zhuravlyov

Альянс и Игорь Журавлёв

Intro by Morgan Henson

Alyans (Альянс) was a Soviet and Russian new wave and synth-pop band formed in 1981 in Moscow by Sergey Volodin and later fronted by Igor Zhuravlyov, who became the band’s most recognizable face and voice. Initially inspired by the emerging new wave, synth-pop, and post-punk movements from the West — particularly bands like Depeche Mode, Ultravox, and Joy Division — Alyans crafted a sound that stood out in the Soviet rock underground for its clean, melodic synthesizers, atmospheric arrangements, and melancholic yet hopeful tone.

Their first big break came with their 1984 album, I Slowly Learned to Live (Я медленно учился жить). However, in 1984, Alyans was banned from performing for being “too closely aligned with Western culture” and for “lacking in ideas.” 1984 was the final year of a campaign in the Soviet Union to target practitioners of counter culture. Unable to perform or record, Alyans disbanded.

However, in 1986, with onset of glasnost, they quietly reformed and resumed their flamboyant, hypnotic, and often quasi-sexual performances. They recorded a new album, Give Me Some Fire! (Дайте огня!) – re-released in 2018 as At Dawn (На заре). However, soon after regaining popularity, the members began to clash with one another over “creative differences” and the band began to move away from its original sound.

In 1990, the band had transitioned to a more traditional Slavic sound and recruited Inna Zhelannaya as a lead singer. The result was Made in White (Сделано в белом). Alyans then dropped their name and reformed as Farlanders under Zhelannaya.

Starting in 2000, the band began reuniting for certain performances. In 2018, they began releasing new music again, in their old style, starting with I Want to Fly! (Хочу летать!). They are still together, still producing music, and still performing today.

Nautilus Pompilius and Vyacheslav Butusov

Наутилус Помпилиус и Вячеслав Бутусов

Intro by Julie Hersh and Josh Wilson

Nautilus Pompilius was founded in 1982 in Sverdlovsk (now Yekaterinburg, Russia) by Vyacheslav Butusov and Dmitry Umetsky. They started at the Sverdlovsk Rock Club with a sound heavily influenced by Western rock and post-punk, sounding a bit like early Pink Floyd or Led Zepplin. They later mixed in more electronic and, as they matured, their sound became much closer to hard rock and orchestral.

Butusov thought he would be an architect initially, and enrolled in an architectural institute, but there he met Dmitry Umetskiy, and the two started to play music together seriously. They released an eclectic collection of songs that they recorded themselves called Transfer (Переезд) in 1983.

Their breakthrough came in 1985 with their album The Invisible Man (Невидимка), recorded with Ilya Kormiltsev, which featured the hit song “The Last Letter” (“Последнее письмо“), a song that was originally recorded with a single synthesizer under amateur conditions. The song became better known as “Goodbye, America” (“Гудбай Америка”), and was re-recorded and featured on the album King of Silence (Князь тишины) in 1988. That studio album was considerably more polished and solidified their reputation as one of the most innovative and emotionally powerful bands of their era.

Part of the band’s cult following came from their partnership with director Alexei Balabanov. They were on the soundtrack of Balabanov’s first film There Used to Be a Different Time (Раньше было другое время), the title of which is actually from the Nautilus Pompilius song “Nobody Will Believe Me” (“Никто мне не поверит“). The band also made up the majority of the soundtrack of the Balabanov’s cult classic 1997 film Brother (Брат) where Butusov had a cameo, playing himself. “The Last Letter” also appears in the sequel, Brother 2 (Брат 2). The band frequently appeared on the Vzglyad musical program, which aired on the USSR’s most popular television channel.

The band moved to Leningrad in 1989, to gain access to the greater resources available there to rock musicians. They played concerts at the Leningrad Rock Club and were one of the more profitable groups performing.

The band broke up more than once, had considerable changes to its lineup over time, and even saw legal battles between Butusov and Umetsky for the rights to its name (Butusov prevailed). However, despite internal conflicts, under Butusov’s leadership, they continued to produce popular music, releasing hits like “Breath” (“Дыхание“), “Walking on Water” (“Прогулки по воде“), and “Wings” (“Крылья“). They released some 15 albums over the course of the band’s life.

After a farewell tour, the band broke up for good in 1997, although they have had reunions three times since then.

Butusov pursued a solo career afterwards. His first album, IlLegitimate AlChemist Doctor Faust the Feathered Snake (НеЗаконНоРожденный АльХимик Доктор Фауст Пернатый Змей; the interesting capitalization has sadly not extended well to the English translation), came out in 1997 in collaboration with Yuriy Kasparyan (Юрий Каспарян), of Kino fame. He also started a super group, U-Piter (Ю-Питер), with former members of Kino, Aquarium, and Wine. In 2000 Butusov started yet another project, Deadushki (Deadушки), with Viktor Sologub, formerly of Straniye Igri. Butusov has also written several works of fiction, including the Virgostan (Виргостан) novels, and has had exhibits of his art.

Strange Games and the Sologub Brothers

Странные игры и Братья Сологубы

Intro by Josh Wilson

Strannye Igry (Странные игры), or Strange Games, was a Soviet new wave and post-punk band that emerged in the early 1980s in Leningrad (now St. Petersburg). The band was founded by musicians and brothers Viktor and Grigory Sologub, who had previously played in other underground groups. Influenced by Western punk, ska, and new wave music, Strannye Igry developed a unique style that combined sharp, danceable rhythms with satirical and surreal lyrics.

Throughout the mid-1980s, the band participated in various state-sponsored rock festivals. They were regular performers at the Leningrad Rock Club’s annual festivals, where they gained critical recognition. Despite occasional clashes with authorities due to their unconventional stage antics and subversive lyrics, they managed to stay active and release new material.

The band’s rise to prominence came in 1982 when they began performing at the Leningrad Rock Club and really took off after they opened for Aquarium. Their energetic and visually striking performances gained them a loyal following, and they became known for their ability to mix humor with biting social commentary. Their first album Metamorphoses (Метаморфозы), was released in 1983, which showcased their eclectic sound and ironic, playful tone. They only released one other album, Keep Your Eyes Open (Смотри в оба), a darker and more hectic album. The band had already broken up by the time the album was released in 1986, with all members departing for other bands.

The Sologub brothers formed a new band called Igry that released two albums, both in 1989. Viktor Sologub shortly after helped launch an electronic project called Deadushki with Vyacheslav Butusov, formerly of Nautilus Pompilius.

Despite their relatively short existence, Strannye Igry left a lasting impact on Soviet alternative rock, influencing later Russian ska and punk bands.

Secret

Секрет

Intro by Julie Hersh

Secret (Секрет) was founded in 1983 in St. Petersburg (then Leningrad), when two of the original four members, Maksim Leonidov (vocals, guitar, keyboard) and Nikolay Fomenko (vocals, bass guitar), met at the Leningrad State Institute for Theater, Music, and Cinematography. They were soon joined by Aleksey Murashov (drums) and Dmitry Rubin (guitar, vocals). According to the group’s website, they started out with a strong desire to play but not much skill. Apparently Leonidov suggested that they try to imitate ABBA; Fomenko countered with the Beatles, they agreed on the Beatles, and a Soviet legend was born. Even the group’s name is taken from a Beatles song, “Do You Want to Know a Secret?” Many of their songs do have an uncanny resemblance to early Beatles hits but most of their inspiration was taken from 1950’s America rock and roll in general.

Their first concert was given as an opener for Mike Naumenko. The group was not well rehearsed and made a lot of mistakes to which the audience responded by throwing bottles at them and demanding the headliner. Apparently the cops were called and the whole concert was broken up.

Despite this clumsy beginning, the group gained traction after Andrey Zablyudovskiy (vocals, guitar, viola) joined, replacing Rubin, and the group found its sound and began to find a fan base. Although this lineup alteration was pivotal to their history, the band never had an absolute front man.

Secret’s first album, 1984’s You and I (Ты и я) featured their early hits “A Thousand Records” (“Тысяча пластинок“) и “She Doesn’t Understand” (“Она не понимает“), songs they later performed at the Leningrad Rock Club. Then, starting in 1985, they were quickly snapped up by the USSR’s expanding official rock industry. They signed with LenConcert, the official concert organizer in Leningrad, and began opening for bard and shanson practitioner Alexander Rozenbaum. They were signed by Melodiya, the official Soviet record company, and put out Beat Quartet Secret (Бит-квартет «Секрет»), their biggest hit album, in 1987 as an official vinyl record. It featured “My Love is on the Fifth Floor” “Моя любовь на пятом этаже,” and “Hi” (“Привет“) their most memorable hits.

Secret proceeded to release new music every year until 1991, including 1989’s Leningrad Time (Ленинградское время) which featured the hit of the same name. Also in 1989, they received permission to tour Europe with Mashina Vremeni. Their sound eventually evolved to contain harder electric guitars and more jazz as well as energetic rock inspired by the 80s. However, they became less known for their new music and more known as entertainment personalities as time went on. They appeared in films, wrote and stared in a stage play about Elvis Presley, and appeared on numerous TV shows, eventually hosting their own comedy and music programs.

Leonidov left in 1990 unexpectedly and moved to Israel. This slowed the group down, but they continued performing as a trio, and released another three albums before finally breaking up in 1997. However, the group’s members, including Leonidov, continued to maintain celebrity profiles. They reunited a number of times and even occasionally released singles until, in 2013, they reunited permanently. They released two new albums, including All This Is Love (Всё это и есть любовь) and have contributed original compositions to films and other projects. They also created a musical called Fear Nothing, I’m with You (Ничего не бойся, я с тобой), based on 23 of the group’s hits. It became the highest grossing theatrical production in Russian history.

They continue to record, perform, and, of course, appear on TV as recognizable personalities.

Bravo and Zhanna Aguzarova

Браво и Жaнна Агузaрова

Intro by Julie Hersh, Morgan Hensen, and Josh Wilson

Bravo (Браво) was formed in Moscow in 1983. It was known for eccentricity and would draw on swing, rock-a-billy, new wave, jazz, and surf rock.

Bravo’s initiating force was Evgeniy Khavtan, who had the idea for the band when he was a student at the Moscow Institute of Railway Engineers. However, the band found their unified style and charismatic front man in Zhanna Aguzarova, a vocalist, actress, and fashion enthusiast. By spring, 1984, the group had recorded a self-titled album, played concerts with some of Russian rock’s greatest names, and appeared on television.

Then, in March 1984, state security officers disrupted one of their concerts, accusing the band of entrepreneurship in illegally selling tickets, a crime under Soviet law. As they were investigating, they discovered that Aguzarova’s state-issued passport listed her as Ivona Anders, a stage name she used. She had decided that she liked the name so much that she had illegally applied for a new passport with that name and somehow managed to receive it. She even had a false backstory for the name that she was a daughter of Swedish diplomats. She was arrested, sent first to Butyrka Prison, then transferred the Institute of Forensic Psychiatry and, upon recognition that she was actually sane, was sent to forced labor in the timber industry in her native Tyumen Region of Russia.

Bravo was essentially lost without her, but reformed upon her return. They were able to join The Moscow Rock Laboratory, giving them legal status. Aguzarova proved again her ability to make contacts and take the band places. Soviet mega-star Alla Pugacheva started inviting them to perform at concerts she organized. They appeared on television again, participated in a large number of rock festivals, and, in 1987, were signed by Melodiya, the major Soviet music company, to make an officially pressed vinyl record.

However, Aguzarova disliked working with the USSR’s official music industry and preferred to take the band back underground and independent. The rest of the band, however, disagreed. In 1988, Aguzarova left the group to begin her solo career. In 1990 she graduated from the Ippolitov-Ivanov Music School and worked at the Alla Pugacheva Theater for a short time. She has worked on collaborative projects with other musicians, acted in movies, occasionally performed in reunions with Bravo, campaigned for Boris Yeltsin, and, of course, released her own music. He last album was Be With Me (Будь Со Мной). Although she remains active and retains her flamboyant appearance when in public, she is also reclusive and is famous for not leaving her apartment for months at a time.

Bravo, meanwhile, has changed its front man twice, but has successfully continued its career without Aguzarova, largely keeping the style that she set for them. They continue to tour regularly. Their last studio album was 2015’s Forever (Навсегда).

Crematorium and Armen Grigoryan

Крематорий и Армен Григорян

Intro by Zachary Hicks and Josh Wilson

Crematorium (Крематорий) is a Russian rock band formed in 1983 in Moscow. They are known for dark, surrealistic lyrics, eclectic musical style, and macabre sense of humor. The band’s front man and founder, Armen Grigoryan, became the defining creative force behind Crematorium, bringing together diverse musical influences: folk rock, psychedelic rock, and cabaret music. Grigoryan’s fixation on themes of death, decay, and existential absurdity, often presented with a sardonic and often carnival-like twist, has drawn comparisons to Western acts like The Doors and Frank Zappa, as well as to Soviet absurdist literature.

In the beginning, Crematorium played underground shows in Moscow apartments before graduating to rock clubs around the city. In 1984, Crematorium began performing at the Moscow Rock Laboratory and, in 1985, the Moscow Rock Festival. That same year, they released their debut album, Illusory World (Иллюзорный мир), which featured their now-iconic song “Little Girl” (“Маленькая девочка“) — a twisted lullaby about a young girl with a doomed fate, encapsulating the band’s signature blend of morbid storytelling and playful melody.

In 1988 Crematorium released their classic album Coma (Кома), for which they won Best Album of 1988, and the music video for “Trash Wind” (“Мусорный ветер”) made onto mainstream television channels. At this time, Crematorium began touring the Soviet Union in earnest and playing to much larger crowds.

Throughout its more than four decades of existence, Crematorium has released a steady stream of new material and toured regularly. This has included concept albums like Zombie (Зомби), released in 1991, and Invisible People (Люди-невидимки), released in 2016, as well as ambitious projects like 1996’s Double Album (Двойной альбом). The latter being their most successful album to date.

Although the group has remained artistically edgy in its sound and its subject matter, they have remained steadfastly apolitical. Today, Crematorium continues to release new music and actively tour both in Russia and internationally.

Alisa and Konstantin Kinchev

Алиса и Константин Кинчев

Intro by Zachary Hicks

Alisa (Алиса) is a legendary Russian metal and hard rock band. Starting in St. Petersburg in 1983, Alisa has since released 25 studio albums to date and spawned an entire subculture of fans known as the The Alisa Army (Армия АлисА), notorious for their wild behavior at concerts.

Alisa formed out of the ashes of Soviet psychedelic rock groups Crystal Ball (Хрустальный шар) and Golden Time (Золотое время). Their name was taken from the title character of Alice in Wonderland. Alisa quickly saw wide popularity following their first concert at the Leningrad Rock Club in 1984, where they performed the now-popular hits “Us Together” (“Мы вместе”) and “My Generation” (“Моё поколение”) for the first time. In 1985, Alisa released their first studio album, Energy (Энергия), which included snippets from classic Russian literature, including Nikolai Gogol, Mikhail Bulgakov, and Nikolai Ostrovsky.

Not long after this first release, the “father” of Alisa—Svatoslav Zaderij (Святослав Задерий)—left the band, and the role of “leader” was taken on by vocalist and actor Konstantin Kinchev (Константин Кинчев), who leads the group to this day. Through the 1980s, Alisa became known for its rowdy concerts, which drew the ire of Soviet authorities.

In 1987, a newspaper claimed that Kinchev was a follower of Hitler and that the band disseminated Nazi propaganda. After a year-long legal battle, the paper published a retraction. The experience led to the title of Alisa’s album A. 206, pt. 2 (Ст. 206 ч. 2), an allusion to the Soviet penal code dealing with “hooliganism,” a catch-all offense that was used to prosecute many different crimes.

During the 1990s, Alisa released a slew of successful albums. Notably, Kinchev converted to Russian Orthodoxy at this time, and since then much of Alisa’s lyrical production has been about God, religion, and patriotism. By the early 2000s, these themes became even more pronounced, even as Alisa’s music shifted its sound away from hard rock and more solidly toward heavy metal. Many bands followed this trend and to this day, patriotism is a common trope in Russian heavy metal. The 2003 and 2005 albums It’s Already Later Than You Think (Сейчас позднее чем ты думаешь) and Exile (Изгой) are indicative of this trend.

Alisa still actively tours, performs, and records today.

Televizor and Mikhail Borzykin

Телевизор и Михаил Борзыкин

Intro by Katheryn Weaver and Josh Wilson

Televizor (Телевизор) was one of the most outspoken and politically charged rock bands to emerge from the Leningrad underground scene in the 1980s. They ironically formed in 1984, the final year of a campaign by the state to closely follow and prosecute any infraction by Soviet citizens participating in counter culture. Mikhail Borzykin, the band’s front man, vocalist, and primary songwriter, quickly developed Televizor’s reputation for sharp, confrontational lyrics and cold, electronic sounds, heavily influenced by Western new wave and synth-driven post-punk acts like Depeche Mode and Joy Division. Borzykin’s powerful stage presence and unflinching critique of the Soviet system made Televizor one of the most controversial and daring bands of their era.

The band burst onto the Leningrad music scene, winning both the 1984 and 1985 editions of the Leningrad Rock Festival. Their first major hit, “Your Daddy is a Fascist” (Твой папа — фашист), featured on their 1985 album A Procession of Fish (Шествие рыбы), openly criticized state authority, censorship, and social conformity in the USSR. While many Soviet rock bands adopted subtle metaphors to avoid censorship, Borzykin’s lyrics were unusually direct — an act of defiance that placed him under heavy scrutiny from Soviet authorities.

At the 1986 Leningrad Rock Festival, Borzykin railed against state censorship throughout the performance. Afterwards, the band received a six-month performance ban and, even after, Televizor remained was often denied performance and recording space. Undaunted and still broadly popular, Televizor still got a spot at the 1987 Leningrad Rock Festival, where they came out with an even more confrontational and socio-politically charged act than the year before. They performed “Three or Four Bastards,” (“Три-четыре гада”), “A Fish Rots from the Head,” (“Рыба гниёт с головой”), “Your Father Is a Fascist” (“Твой папа – фашист”), and their song “Children are Leaving” (“Дети уходят“) even won best song that year.

Later that year, in Yalta, the authorities banned Televizor from performing five minutes before the start of a concert. Borzykin, never willing to back down, called everyone who had gathered for the concert to follow him on a march to the office of the local Communist Party Secretary, where he successfully demanded, via megaphone, the reinstatement of his concert. When another sudden cancellation occurred in Leningrad not long after, Borzykin performed the same feat again. Despite these run ins, the band was also able to gain rare official permission to tour internationally and appeared in Germany, Denmark, Holland, Belgium, France, Italy, and Luxembourg.

By the late 1980s, Televizor had become a symbol of musical dissent in the Soviet Union. Their 1987 album, Homeland of Illusions (Отечество иллюзий), featured songs that addressed state violence, cultural stagnation, and individual repression. Borzykin also made headlines for his public denunciations of the Soviet-Afghan War, an extremely taboo subject at the time.

The band itself had contentions within it. Infighting and band members departing for other groups led to the Televizor’s dissolution in 1991. Borzykin relaunched the group in 1992, but it collapsed again in 1995, and reformed for the second time only in 2004. That year, they released the album Megamisanthrope (Мегамизантроп). Their final album, the crowd-funded Ichthyosaur (Ихтиозавр), was released in 2016. Televisor is still technically together – but now has only Borzykin as a permanent member. He performs everything himself and then mixes it together digitally. Televisor has not performed as a group since 2021. Borzykin’s last solo performance occurred in 2023.

Borzykin was highly active in protest movements after the fall of the USSR, protesting corruption under Yeltsin and Putin. He was a celebrity participant in the March of Dissent, and other actions organized by the Russian opposition. He continued to write songs that skewered Putin’s government, major corporations like Gazprom, and even put out a song called “Forgive Us, Ukraine” (“Ты прости нас, Украина”) in 2015, after Russia annexed Crimea. However, his last album was released in 2016 and he himself has been living outside of Russia since 2019.

Nol’ and “Uncle” Fedor Chistyakov

Ноль и “Дядя” Фёдор Чистяков

Intro by Katheryn Weaver

Nol (Ноль; meaning “Zero” in Russian), was founded in Leningrad in 1985 by “Uncle” Fyodor Chistyakov. Nol’ was known primarily for their blending of folk and ska, which was elevated by Chistyakov’s energetic accordion playing, a rare feature in Russian rock at the time, which gave their music a uniquely raw and rebellious feel. Their lyrics were politically charged and often surreal. The other members were Alexei Nikolaev and Anatoly Platonov.

Their first album, Music of Fighting Files (Музыка драчёвых напильников) was recorded by the legendary Andrey Tropillo in 1985. Tropillo recorded many young bands for free with equipment at the House of Young Technicians, giving many their first breaks. The group later became active in the Leningrad Rock Club in 1986, and subsequently toured throughout Russia.

In 1989, Nol’ released their popular second album, Stories (Сказки). Nikolaev then left the band for a period to serve in the Soviet Army but returned to record their third album, Northern Boogie (Северное буги). Nol’s most popular album, the ironic Song of Unrequited Love for the Motherland (Песня о безответной любви к родине) was released in the autumn of 1991.

Nol’ took a five year hiatus after Chistyakov was charged with attempted murder of his common law wife in 1992. The court found him insane and sentenced him to treatment in a mental hospital. Immediately after his discharge, Chistyakov joined the Jehovah’s Witnesses. During this time, the remaining musicians in the group recorded the album Nonsense (Бредя) under the name Zero Without a Stick (Ноль без полочки).

The band briefly reconnected between 1997-8 and tried to reformulate themselves under different names, including Fedor Chistyakov and the Orchestra of Eclectic Folklore, and Fedor Chistyakov and Nol’.

In July 2017 the band introduced their first single in 20 years, “Time to Live” (“Время жить”). Less than a month later, while on tour in America, Chistyakov announced that he would cancel all scheduled Russian concerts and remain in New York. He announced that his “defection” was influenced by both the arrest of film director Kirill Serebrennikov and a Russian Supreme Court ruling that the Jehovah’s Witnesses, a religion he still follows, were extremist and were to be forcibly disbanded.

The current status of the group is undecided. Although their existance was off-and-on, they are remembered as pioneers at making Russian folk a centerpiece of their rock/punk/ska style.

Sources to Research Russian Rock

Ryan Hardy

The brief list of online resources has been compiled for those interested in understanding late-Soviet music movements, particularly for rock and punk movements of Leningrad.

I. Resources in English

A. Lecture on Russian punk