The Latvian daina is far more than a folk song. This tradition stretches back over a millennium, with some examples preserving linguistic forms long lost in modern Latvian. These songs are credited with recording Latvia’s prehistory and sustaining its culture through centuries of foreign rule. Dainas were central to the Latvian National Awakening, which eventually resulted in the Latvian state, and later the Singing Revolution that helped end Soviet rule.

Today, the Latvian Song and Dance Festival, held every five years with up to 40,000 performers and nearly half a million attendees, almost a third of Latvia’s population, celebrates the daina. For Latvians, the songs are not just music, but a cornerstone of Latvian identity and patriotism.

What is a Daina?

Most dainas are just four lines long and follow a simple rhythm and structure. About 95% are written in trochaic meter. This means that they feature a strong beat followed by a weak one, creating a steady, almost rocking flow that makes the songs easy to sing and remember. Each line is divided into two balanced parts, with a natural pause in the center. The other 5% of these poems tend to be in dactyl meter, featuring a strong beat followed by two weak ones but with an otherwise similar structure.

Because each daina and each line of a daina is short, the vocabulary used in them is somewhat limited. Words need to fit neatly into the rhythm—sometimes a four-syllable word, sometimes two shorter words, or other small combinations. In some eastern dialects, singers occasionally bend the rules, shifting the pause slightly to allow longer or shorter words. Even then, the rhythm and balance are preserved, keeping the song recognizable and singable. Sometimes, to keep the flow and meter, they may end with a refrain, such as “līgo” or “rotā” or “ramram tai radi ridi rīdi” in order to fill the space needed.

There is also a split between the two halves of the four-line daina. The first two lines express a thesis and the second two an antithesis or elaboration. So, for instance, the first two lines might discuss the spiritual, natural, or sacred:

| Saule brida rudzu lauku,

Zelta kurpes kājās bija. |

The sun walked through the rye field,

Golden shoes upon her feet. |

While the next might discuss the temporal, human, or secular, usually with a mirrored structure:

| Meitas brida rudzu lauku,

Sudraboti vainadziņi. |

The maidens walked through the rye field,

With silver wreaths. |

Thematically, dainas cover just about every subject. There are dainas about nature, peasant life, mythology, historical events, agricultural seasons, and health. The songs are the keepers of Latvia’s oldest wisdom, memory, and worldview. There are even “drinking” dainas, which can be bawdy and explicit. They are most known, however, for encoding values of community, morality, and respect for nature, while also preserving fragments of Latvia’s prehistory.

Poetic devices such as metaphor, simile, hyperbole, repetition, and alliteration are common in dainas, but rhyme is rare. According to Latvian-American translator and author Ieva Auziņa Szentivanyi, “rhyme would counteract the delicacy of most dainas and would be unappealing to the Latvian ear.”

How and Where are Dainas Sung?

Dainas can be performed in many ways. They can be sung individually, repeated, or strung together. The natural rhythm of each poem means that it can be simply recited or chanted aloud in addition to being sung. They are often performed in this way by individuals, for instance, by mothers to infants and children. They are also commonly given as blessings or toasts at weddings, funerals, or celebrations of birth.

Some are work songs meant to add rhythm and social bonding to work flows in fields or cottages. Some were meant to be sung by groups during celebrations such as Ligo, the pagan-rooted midsummer festival that stands as Latvia’s main national holiday. In these instances, there is often a lead singer, or teicēja, who will start the song. The same text is then repeated by a second singer, or locītāja, so that the verses fold on top of one another. The rest of the group joins as vilcējas, which literally means “pullers,” who sing a single vowel sound over the top. This type of singing is known as bourdon, a French word for “bumblebee.” An excellent example of this type of seeing can be seen from Suitu Sievas, a folk group that records Latvian folk songs in traditional presentations.

The teicēja is expected to have a powerful voice strong enough to rise above the other singers and potentially hundreds of dainas in her repertoire. Although the dainas are short, this type of singing can be sustained for hours.

Another arrangement was a sort of competitive singing where two groups, for instance, at a wedding, would sing back and forth to each other, often trying to best the other in friendly taunts with existing dainas or those made up on the spot.

Latvia has considerable regional diversity – these forms are more common in some regions than they are in others.

Today, the most popular presentations of dainas are choral versions, sung by small or even very large groups who sing rehearsed, usually polyphonic arrangements. There are today many groups and choirs dedicated to this type of singing in Latvia.

Dainas sung in any of these forms are usually sung acapella, but can be accompanied by instruments. Common folk instruments include flutes or horns made of reeds or goat horns. Sticks or even saplings hung with bells and chimes were common at ceremonial performances. The kokle, a box zither with five to twelve or more strings, can be considered Latvia’s national instrument and is often used to accompany folk music.

Recording and Preservation of Dainas

Although the daina has a very long history of oral tradition, they long went unrecorded. The first instance of a written daina occurred in the court proceedings of a group accused of witchcraft in Riga in 1584. Friedrich Menius, a Swede, was the first to record some songs in a scholarly way in his “Essay on the Origin of the Livonians” in 1635. Scholarly interest continued in the songs and their connection to the ethnography and history of Latvia continued and, by the late 19th century, about a few thousand examples had been gathered and recorded by various groups.

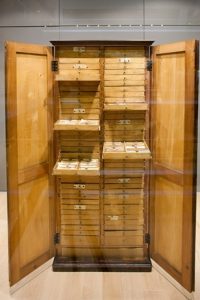

Building on this, Latvian folklorist Krišjānis Barons began the first systematic collection beginning in 1873. Thousands of respondents sent him examples from all over Lavia. Barons had a special filing cabinet built with 70 drawers to store and categorize the songs on small cards. The Cabinet of Folksongs (dainu skapis) was eventually filled with more than 200,000 unique examples. It would be used as the basis for the publication of the influential six-volume Dainas of Latvia (Latvju dainas), which contained more than 300,000 examples.

Barons’ aim was not only to collect and systematize the dainas – the ultimate purpose was to help unite Latvians during the period of National Awakening in the late 19th century. His was an effort critical to that era that say Latvians see themselves as a united and independent nation for the first time. Today, he is a national hero. Dainas of Latvia enjoyed two additional printings after Latvia declared independence in 1917. It remains in publication today and is regarded as a foundation of Latvian national identity. This cabinet is now located in the National Library of Latvia in Rīga.

His work has been continued by many others and remains a work in progress today. Approximately 1.4 million four-line dainas are now held in collections across the world. There is also a searchable virtual online repository of dainas sponsored by several Latvian cultural organizations and UNESCO.

For more on Latvian history, see this article at our sister site, GeoHistory.

Translating and Understanding Dainas

While gathering the dainas has been a monumental task, making dainas accessible to the outside world has also been a major challenge. Dainas are very short, highly structured, and also very specific in their content and vocabulary. Dainas make use of ancient agrarian understandings and folk symbolism. For example, an ancient Latvian would intrinsically understand that a skylark represents happiness and light, while a crow indicates something more sinister. When translated directly, these subtleties are lost and the poetry becomes either hazily abstract or even unintelligible to a modern reader.

The structure, coupled with the differences between Latvian and English also complicate translation. Differing stress rules and the requirement of articles in English and their absence from Latvian complicate the cadence, making a faithful and properly metered translation extremely complicated. In addition, dainas make ready use of diminutives, which are common and varied in Latvian but much rarer in English. Diminutives are important in creating an atmosphere of tenderness and affection.

The historical era depicted in the dainas is also very difficult to pinpoint exactly. Sometimes, particular words and phrases or certain objects mentioned can help one to sleuth and narrow down the century, sometimes even the decade (if a particular event or object is mentioned), but most frequently the exact age of a text is almost impossible to determine. The dainas in their current form are a “snapshot” of an ever-evolving, constantly changing oral heritage, where each individual singer may – most often unwittingly – add to or change the text.

Ieva Auziņa Szentivanyi, who passed away in late 2024, was Latvia’s foremost daina translator. Before she undertook her work, dainas were considered by most to be impossible to translate into English. Her volumes remain some of the only English-language translations that include extensive contextual information and remain as faithful as possible to the meter of the original piece.

Political Implications of Dainas

Because dainas are so central to Latvian identity and evoke a strong sense of unity, they have often been tied to political movements.

This was evident during the Latvian National Awakening of the 19th century during which dainas were widely collected. At a time when Latvia was under Russian rule and the German elite dominated cultural life, dainas offered proof of a rich Latvian heritage equal to that of any other European nation. They became a unifying symbol, helping Latvians see themselves not as scattered peasants but as members of a single nation.

Even more important to modern identity, dainas were at the forefront of Latvia’s successful efforts to break away from the Soviet Union and revive their independent Latvian state. Although there were efforts to suppress Latvian nationalism, dainas were too prominent and, instead, the Soviets tried to coopt them through control of the Latvian Song and Dance Festival, which predated the Soviet takeover. In the coopted festivals, approved dainas were sung alongside patriotic staples. However, the songs remained a subtle form of cultural resistance, conveying covert messages of strength and unity, undecipherable by the occupying authorities.

This came to the forefront during the peaceful Singing Revolution, which began in 1987. Spurred by Gorbochev’s prestroika-era reforms that allowed for more permissive expression, Latvians gathered for demonstrations in Riga calling for recognition of past Soviet crimes from the Molotov–Ribbentrop Pact to the mass deportations of Latvians and the many political imprisonments suffered by Latvians. The protesters performed traditional dainas and national songs banned or censored under Soviet rule. Music provided both a peaceful outlet for resistance and a deeply symbolic expression of Latvian unity.

Based in large part on the success of these protests, in 1988, the Latvian Popular Front was formed, uniting intellectuals, activists, and ordinary citizens. Song festivals became rallies for independence, with crowds of hundreds of thousands raising banned flags and singing songs that affirmed national identity. The 1989 Baltic Way, a human chain that stretched through the countries of Estonia, Latvia, and Lithuania, demonstrated Baltic solidarity against oppression.

Even today, dainas retain political weight. Latvian politicians frequently invoke them in speeches to emphasize cultural continuity or national unity. The state actively supports their preservation, sponsoring research, translations, and performances, most visibly through the Latvian Song and Dance Festival, discussed in more detail below.

Dainas in Performance Today

The daina, centuries old, continues to thrive today. The Latvian Song and Dance Festival, founded during the National Awakening in 1873, kept alive even under the Soviets, and held every five years to the present day, is the most prominent venue for their performance. Designed to celebrate the songs as part of a uniquely Baltic and Latvian cultural identity as well as to elevate them through choral presentations, the festival has maintained its significance and popularity. The event gathers tens of thousands of performers and nearly half a million spectators. Attending the festival is akin to a pilgrimage, with many representatives of the Latvian diaspora flying in just for the event.

The songs are also still sung by ordinary Latvians – at weddings and on holidays, at family gatherings and to sooth children.

In addition to traditional presentations such as those by Suitu Sievas, the daina has also entered popular culture, with fusion groups drawing inspiration from traditional dainas to create new ethno-jazz, pop, and rock music. Tautumeitas, for instance, was featured on Eurovision, with modern polyphonic arrangements of traditional dainas. Their name translates to “Folk Maidens.” Iļģi, meanwhile, performs Latvian folk with world music and rock influences. Skyforger has blended them into heavy metal.

In 2003, UNESCO recognized the songs as part of the Oral and Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity. Abroad, the Latvian diaspora has preserved the legacy of song by establishing their own singing festivals. For instance, there is a regular Latvian Song and Dance Festival held in Grand Rapids, Michigan, the home of a large Latvian population, more than 7,000 kilometers from where the first celebration was held in 1873.

Conclusion

The contribution of the daina to Latvian identity cannot be understated. Dainas have represented a bridge to the ancient history of Latvia. Deeply embedded in the national consciousness, the songs were used to build a national identity under the First National Awakening and retain that identity under decades of Soviet rule. Latvians see these numerous short songs as representing their shared history, culture, and struggle against tyranny. They are also ways of marking special occasions, celebrating holidays, and building social bonds. They remain a foundational element to the national identity. The daina has always been entertainment, certainly, but concurrently it conveys important cultural values and was instrumental in the unification of a nation and a people that toiled and triumphed as one.

You’ll Also Love

The Latvian Daina: How Four-Line Folk Songs Helped Birth A Nation

The Latvian daina is far more than a folk song. This tradition stretches back over a millennium, with some examples preserving linguistic forms long lost in modern Latvian. These songs are credited with recording Latvia’s prehistory and sustaining its culture through centuries of foreign rule. Dainas were central to the Latvian National Awakening, which eventually […]

From Folk to Future: Localizing Sound in Modern Ukraine

In the decades since Ukraine gained independence, music has played a vital role in shaping and expressing a modern sense of national identity. This has been especially visible in the creative ways artists have drawn from the country’s folk traditions—adapting village songs, instruments, and motifs into new genres that resonate with contemporary audiences. Whether through […]

The Dombyra: The Kazakh’s Musical Soul

The dombyra (домбыра) is a lute-style instrument. It is an ancient and quintessential piece of Kazakh culture and identity. In its most popular form, the dombyra has two-strings strung down a long, skinny neck and a pear-shaped body, flat at the front and rounded on the backside. The standard English spelling of dombra is taken […]

Six Georgian Bands Bringing Traditional Polyphony into the Pop Music Age

Georgian polyphonic singing, added to the UNESCO Representative List of the Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity, is a musical technique in which a single song has several melodies, each sung concurrently, with no one tune dominating the others. In Georgia, the style varies by region, but the practice reflects both military, folk, and religious culture. […]

Żywiołak: Pagan Rock from Poland with a Modern Mindset

Żywiołak, initially formed in Warsaw in 2005, is a Polish folk rock band steeped in mythos. Its name references the Elemental, a magical being said to harness the power of nature in the form of air, fire, water, or earth. Their lyrics sing of epic battles (in Wojownik, or Warrior) and explore the traditions of […]