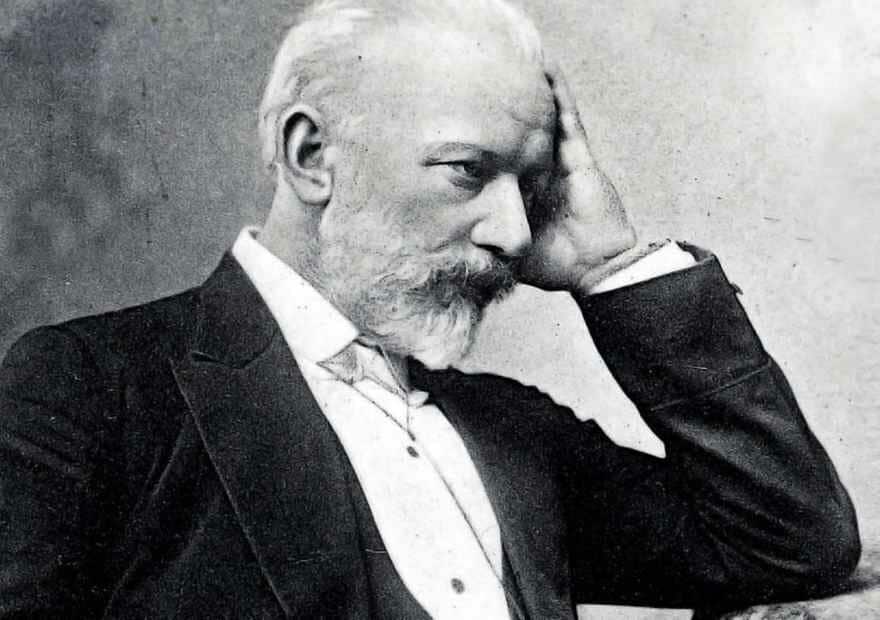

Pyotr Tchaikovsky, a leading Romantic composer from Russia, is beloved for his emotionally charged symphonies and ballets like Swan Lake and The Nutcracker. Despite initial training for a civil service career, his passion for music led him to the St. Petersburg Conservatory. He gained international recognition for his innovative compositions that blended Russian folk influences with his own unique style, leaving a lasting legacy on classical music.

The Russian composer’s works can be found today not only in concert halls across the world, but also used in popular culture as recognizable and emotionally affecting pieces. For more on his the museum and memorial concerts that are given for him in Russia, see this article on MuseumStudiesAbroad, our sister site devoted to museums and remembrance.

The Life of Pyotr Tchaikovsky

By Chris Wehberg

Although Tchaikovsky originally trained as a civil servant, his talent was eventually recognized and cultivated by his family and by international teachers. He often found inspiration for his pieces from classic literary works. He would go on to produce his great works while dealing with mental health issues and a failed marriage.

Early Life and Education

Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky (Пётр Ильич Чайковский) was born May 7, 1840, in Votkinsk, Russia, into a well-educated military family. From a young age, Tchaikovsky was interested in music, and particularly in the piano and orchestrina, a musical instrument that imitates the sound of an orchestra, kept in his childhood home. Both his parents, Ilya and Alexandra, were trained in music, which helped further Tchaikovsky’s interest in the subject. At the age of four, Tchaikovsky composed his first composition with his sister Alexandra. At five years old, he started taking piano lessons and learned to read advanced sheet music while still a child.

Despite Tchaikovsky’s virtuosity at such a young age, his parents sent him, in 1850, to the Imperial School of Jurisprudence in Saint Petersburg for civil service, given that musical careers at the time were considered lower class positions. It is also important to note that music studies in higher education was not widespread at the time.

Tchaikovsky entered the school two years earlier than allowed. This was done to ensure the young boy would become as financially independent as possible. He studied at the boarding school for nine years and formed a close life-long friendship with poet and writer, Aleksey Apukhtin.

In 1854, Tchaikovsky’s mother passed away from cholera. He was just fourteen at the time. Already suffering from the emotional trauma of separating with his mother at a young age, her death deepened this pain and lasted for most of his life. It was his mother’s death that inspired him to write his first full composition, a waltz titled My Dear Little Mother. Tchaikovsky renamed this waltz to Mama and incorporated it into Op. 39 Album pour enfants (1878). His father also contracted cholera, but fully recovered and sent Tchaikovsky back to school after his mother’s funeral.

Above: “Mama,” which Tchaikovsky first wrote at the age of 14.

At school, Tchaikovsky involved himself in music as much as he could, despite not formally studying it there. He and his friends occasionally attended the opera, and he attempted to continue learning piano with Franz Becker, an instrument manufacturer who frequented the academy. In 1855, Tchaikovsky’s father finally recognized the professional potential of his son’s talent and decided to recontinue his son’s piano studies and funded private lessons with the teacher Rudolph Kündinger. Kündinger did not believe in Tchaikovsky’s talent, so the young musician soon after sought mentorship from Italian singing teacher Luigi Piccioli. Piccioli was the first individual to truly recognize Tchaikovsky’s musical abilities and is the reason for his lifelong interest in Italian music.

From Civil Servant to Music Professional

In 1859, Tchaikovsky finished his studies and began working for the Ministry of Justice, where he became a senior assistant after just eight months. However, Tchaikovsky remained a senior assistant for the next three years of his brief career in civil service. Uninspired by his civil work, Tchaikovsky began to take classes at the newly founded Russian Musical Society (RMS) in 1861. At RMS, the first public school of music in Russia, Tchaikovsky eventually joined the St. Petersburg Conservatory, where he composed alongside the renowned music theorist Nikolai Zaremba and pianist Nikolai Rubinstein. There, Tchaikovsky developed his understanding of European principles of composition, which allowed him to later blend both European and Russian styles into something unique. Tchaikovsky composed and premiered his first symphony, Winter Daydreams (1866), while at the Saint Petersburg Conservatory which received heavy criticism from Zaremba and Rubinstein. The symphony is described as ‘fully Russian’, with an unpredictable tonality and uncertain key.

After graduating from the Saint Petersburg Conservatory in 1865, Tchaikovsky accepted a position as a professor of music and harmony at the Moscow Conservatory. During this time, he had his first public performance with a piece titled Characteristic Dances. This piece was later reworked into his opera The Voyevoda. Herman Laroche, critic, friend, and teacher to Tchaikovsky, attended the premier of Characteristic Dances and wrote that he was pleased by the performance.

In the late 1860s, Tchaikovsky was starting to be recognized for his work. His pieces were being performed in public more frequently, including the premier of his first operas with mixed reviews: The Voyevoda (1869) and Undina (1870). Tchaikovsky himself was not satisfied with these first attempts and destroyed all the copies. In 1874, he premiered his first surviving opera, The Oprichnik and followed that with Vakula the Smith, which he wrote in 1874 and later won an RMS competition with in 1876. The premier of his First Piano Concerto was conducted by Hans von Bülow in 1875. Tchaikovsky originally asked pianist Nikolai Rubinstein to premier his concerto, but his excessive criticism led Tchaikovsky to seek out Bülow. Bülow was already scheduled to tour the United States, so he debuted the piece in Boston where it received some acclaim.

Above: The Operichnik, the earliest surviving opera written by Tchaikovsky.

Tchaikovsky’s Rise to Fame and Internal Struggles

Much of the academic discussion surrounding Tchaikovsky’s personal life centers on his sexual orientation. Biographers believe that Tchaikovsky was homosexual and had many romantic interests, including fellow classmate Sergey Kireyev during his time at the Imperial School of Jurisprudence. Despite this, he married music student Antonina Milyukova in 1877, while composing the opera Eugene Onegin, which would prepare in 1879. However, Tchaikovsky left Milyukova less than three months after their wedding. He attempted suicide later that year.

After this traumatic year, he travelled and lived abroad throughout Europe and Central Asia for several years. Tchaikovsky lived largely in isolation and estrangement until his return to Russia in 1884. However, he continued to write.

Tchaikovsky received his first widespread critical acclaim for his Third (1875) and Fourth Symphonies (1877-8). Symphony No. 3 is the only symphony composed by Tchaikovsky to have five movements and be set in a major key. It was premiered in Moscow in 1875 by Rubinstein at the first symphony concert of the Russian Musical Society. Perhaps most importantly, Tchaikovsky was satisfied by the performance. Symphony No. 4 was similarly premiered in 1878 by Rubinstein and received even more acclaim. It was also cherished by Tchaikovsky for being one of his few works to not disappoint him.

Tchaikovsky’s most notable instance of universal acclaim came with Swan Lake (1876). The composer based the ballet on the German Folk Tale the White Duck by Johann Karl August Musäus. The 1877 premier of the ballet in Moscow was initially a disaster as audience members, critics, and even Tchaikovsky were all unhappy with the performance. At the center of the disaster was the choreographer, Julius Reisinger, who had modified large parts of the orchestration because he found the original too complex and symphonic to fit the ballet genre.

Only in 1895, two years after Tchaikovsky’s death, would Swan Lake be staged as intended and became the iconic ballet it is today thanks to alterations made by the ballet master Marius Petipa, who stayed faithful to Tchaikovsky’s original score.

Tchaikovsky’s Later Work and Death

1877 did bring Tchaikovsky some happy news, however. Allowing him to focus exclusively on his music, Tchaikovsky began receiving a financial allowance from the widowed Nadezhda von Meck. She served as his patroness for thirteen years, between 1877 and 1890. Tchaikovsky dedicated Symphony No. 4 to von Meck, and the two maintained frequent communication throughout the composition process.

Tchaikovsky international fame rose in the early 1880s, spurred by a movement of unity between Russia and the rest of Europe, and led by novelist Fyodor Dostoyevsky. The rest of the world was now more than ever willing to embrace Russian art and music.

In this period, Tchaikovsky composed two significant compositions, the 1812 Overture (1880) and Piano Trio in A minor (1882). The 1812 Overture served as a commemorative piece for the 25th anniversary of Alexander II’s coronation. It also honored the christening of the Cathedral of Christ the Savior and was featured at the Moscow Arts and Industry Exhibition. The other piece, Piano Trio in A minor, Tchaikovsky wrote for Nikolai Rubinstein, after his peer and mentor died in 1881. After Tchaikovsky’s death in 1893, it was frequently used in memorial concerts for the composer himself.

Tchaikovsky died November 6, 1893, just days after the premiere of his sixth symphony, The Pathétique.

He is largely thought to have died from cholera, but in recent years scholars have considered the possibility that his death was suicide by poison. There is also a theory that Tchaikovsky’s suicide was forced by his former classmates, who did not want his homosexuality, if expressed, to tarnish the reputation of their academy. The Pathétique is sometimes argued to be Tchaikovsky’s suicide letter. The fourth movement greatly contrasts the first three, with a melancholic tone and “crying” violins. Most of his works contain a concrete, satisfying ending, but his sixth symphony fades into nothingness, leaving the audience feeling unsettled.

Tchaikovsky Concert Hall in Moscow: Master Class Performance

By Sarah Parker (2014)

If you’re new to the culture, you’ll soon see that Russians take performance very seriously. Whether it’s orchestra, opera, ballet, or theater, you owe it to yourself to see as many performances as possible, and at least one!

The first stop is the Tchaikovsky Concert Hall (Концертный Зал имени П. И. Чайковского, located at 31/4 Tverskaya St. in central Moscow). It’s easy to find for newcomers to Moscow because it is literally in the same building as the Mayakovskaya Metro Station. Tickets start at 200 rubles, but unlike some venues, even the cheap seats here are great, with an unobstructed view.

I saw the “Master Class” performance. These are students who come to Moscow to study at the prestigious Moscow Philharmonic, under the famous conductor Yuri Simenov. As part of their graduation, they give a concert in this hall. Students are already semi-professional when they enroll as master class students.

This summer’s graduating group came from all over the world: Asia, Scandinavia, South America, Eastern Europe and of course Russia. They all had received multiple awards for their previous work conducting, and had travelled the world with their various projects.

Besides the beautiful music, the theater itself and the philharmonic orchestra are a feast for the eyes. Behind the stage is a modern set of organ pipes, and the room is open and acoustically impressive. We were treated to selections of classical orchestral works by Rachmaninoff, Tchaikovsky, Dvorjak, Stravinsky, Mozart, and Shubert. There were also some newer arrangements of works by Rimsky Korsakov.

In typical dramatic fashion, the most experienced performers and edgy pieces were last, and the build-up was really exciting. The crowd was wild over certain conductors, showing their familiarity with the world of conducting and orchestra. The ability of very young conductors was truly amazing. They led the orchestra through crashing pinnacles followed by pin-drop silence.

While it common for performances in Russia to come with one intermission, this performance had two. During intermissions, guests wander out for coffee and refreshments from little cafes on each floor. The various levels of the theater had different architectural designs, and the third floor resting area is a beautiful place. Afternoon light illuminates stained glass, two stories of classical columns, and a beautiful centerpiece sculpture. A series of bells indicate how much time has passed in the intermission, and you must return to your seat at the third bell! Purchase a program for 100p, it’s always worth it, but not all are available in English. When a crowd really applauds, they begin to applaud in unison, and the performers will continue to bow and receive flower bouquets until the applause stops, but stay to the end to see how each performer, and even the management, receives recognition for their part in the performance.

You Might Also Like

Polish Sung Poetry: Word, Song, Beauty, and Resistance

Sung poetry in Poland has a long cultural and political history. These songs combine literary depth with melody, weaving together stories of history, philosophy, and social life. They have drawn on traditions from medieval bardic music to cabaret and folk music to modern jazz. The genre has also been part of resistance movements during the […]

The Latvian Daina: How Four-Line Folk Songs Helped Birth A Nation

The Latvian daina is far more than a folk song. This tradition stretches back over a millennium, with some examples preserving linguistic forms long lost in modern Latvian. These songs are credited with recording Latvia’s prehistory and sustaining its culture through centuries of foreign rule. Dainas were central to the Latvian National Awakening, which eventually […]

Shanson: Music From Gulag to Mainstream

Shanson, especially as known in Russia, is full of contradictions and notoriously hard to define. Encompassing a range of musical styles, it incorporates bardic tradition and pop, with influences from rock, jazz, Slavic and gypsy folk traditions, vaudeville, cabaret, and “romance” – a Tsarist-era genre that loosely evolved from folk and opera. An important part […]

Polish Rock Under Communism: Resistance, Censorship, and Defiance

Poland under communism experienced censorship and state control of the music industry, but never as fully as in the USSR. Protests and worker uprisings, sometimes at great cost to demonstrators, kept authorities wary and forced them to permit more cultural expression than elsewhere in the Eastern Bloc. Officials, for their part, justified their relative leniency […]

From Folk to Future: Localizing Sound in Modern Ukraine

In the decades since Ukraine gained independence, music has played a vital role in shaping and expressing a modern sense of national identity. This has been especially visible in the creative ways artists have drawn from the country’s folk traditions—adapting village songs, instruments, and motifs into new genres that resonate with contemporary audiences. Whether through […]