Russian soccer caught the world’s attention in 2018, when Russia hosted a very successful FIFA World Cup. The game is Russia’s most popular national sport, ranking just above hockey, and Russia poured millions into new stadiums and renovations on older, Soviet-built stadiums. This construction was made as a point of pride for the Russian government, which partly sponsored and directed the construction, but also as a point of pride for the wide fan base that Russian soccer enjoys and which has always followed its international competitions especially closely.

The following resource will look at the history of the sport in Russia. It will also describe Russia’s top ranked and best known soccer clubs as well as its top league for anyone looking to start following the sport in Russia.

Early History of Russian Soccer

By Josh Wilson

Soccer likely first came to Russia in the early 1880s – not long after its official birth in England in 1863. Foreign workers and engineers brought from Western Europe to work on newly-rising factories in the Russian Empire brought it with them and taught it to their coworkers. Thus, the first clubs rose in such westward-facing port cities as St. Petersburg, Riga, and Odessa.

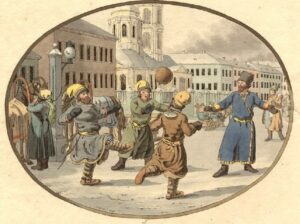

The game may not have been entirely foreign to Russia, however, as, before that, Russia did have folk games that resembled soccer. Shalyga, for instance, required its players to kick a leather ball stuffed with feathers into “enemy territory.” It was often played using a frozen river or basically any other found space. Shalyga was recorded first in 1793 and apparently became popular enough that the Orthodox Church issued edicts against it, as games were often played on Sundays and interfered with church attendance.

Russia’s first officially recorded match was held in St. Petersburg on October 24, 1897, when Sport beat the Vasileostrovskoe Football Community 6:0. Interestingly, most early soccer games in Russia were apparently played using a shalyga ball in a range of found spaces.

Football developed fairly rapidly in Russia. The St. Petersburg City League, the country’s first, formed in 1901 and, by 1912, the All-Russian Football Union had formed. The Tsar got involved as well, fielding a Russian National Team in 1910, which won its first matches against Bohemia and took fourth in the 1912 Summer Olympics in Stolkholm, Sweden. However, the team lost or tied most of the 16 matches it played before the revolution.

Most teams in Tsarist Russia, however, remained attached to factories or community sporting organizations. Those that were first able to be “professional” clubs, with some paid staff, were most often supported by a factory, after which they were most often named.

After the revolution, soccer maintained its affiliations with factories and kept its reputation as a worker’s and a people’s sport. Most of the teams below often trace their official history from the early days of the USSR, although often the teams were formed from merged or reorganized clubs that had existed before.

The Russian Premier League

By Zack Johnson

The collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991 affected nearly every aspect of Russian life and soccer was no exception. Founded in 1936, the Soviet Top Division (the highest level of soccer competition in the USSR), would, after over 50 years of continuous competition, play its final season in 1991. Afterwards, domestic leagues formed in the newly independent states.

Russia’s six teams remaining teams were almost entirely based in the capital: CSKA Moscow, Spartak Moscow, Torpedo Moscow, Dinamo Moscow, and Lokomotiv Moscow. Only Spartak Vladikavkaz, in the Caucasus, represented some of Russia’s diversity. These six original teams were initially joined by 14 additional teams spread across Russia to form a 20-team league known as “Russian Top Division,” which played its inaugural season in 1992.

Over the next ten years, the league evolved into a 16-team top division format, similar to most European leagues. Each year, the two last place teams of the top division are relegated to a lower division known as the Russian National Football League (its official name is in British English, thus referring to its sport as “football”). The two top finishing teams of the lower division ascend to the upper division each year.

In 2001, Russian Top Division was rebranded as “Russian Premier League,” recalling such top European leagues as the English Premier League or Spain’s Campeonato Nacional de Liga de Primera División.

In 2010, the league moved from a spring-fall schedule to a fall-spring schedule, like the rest of the top European Leagues. The change presented new weather-related hurdles, as the original spring-fall schedule had been used to avoid playing during the harsh Russian winter.

One common criticism of the Russian Premier League is that some teams perennially dominate. For example, 13 of the last 19 titles have been won by either Zenit St. Petersburg or CSKA Moscow. Of the ten titles before that, nine went to Spartak Moscow. In fact, in the history of the league, only thrice has the top team come from outside of Moscow or St. Petersburg. Teams in these two largest Russian cities have more easily attracted financing and thus also retained the top talent, leaving teams in Russia’s “provinces” to comparatively flounder.

In fact, the situation gets worse the farther east one goes. Within the top division for 2021-22, only FC Ural of Yekaterinburg sits east of the Urals. Teams from places like Khabarovsk and Vladivostok in the Far East are almost perpetually relegated to the lower leagues.

Expanding the Russian Premier League to Russians beyond European Russia is the next step in making the RPL a truly national league. In fairness, however, such national disparities are hardly rare among European leagues.

In attempts to improve league talent and close the gap on disparities, the Russian Premier League requires its clubs to establish youth leagues, which are mentored by the Premier League team and which participate in an annual Russian Football Youth Championship. The Youth League standings still heavily favor Western Russia – but do at least show strong standings for teams particularly from Russia’s South West in addition to the capitals.

Russian soccer has also become international as its reputation and funding base has grown. Of the most notable international signings, that of Brazilian legend Roberto Carlos and Cameroonian superstar Samuel Eto by Anzhi Makhachkala (based in the capital of Dagestan) and Brazilian national team striker Hulk by Zenit St. Petersburg, stand out.

Global awareness of the RPL has also been increased by the prevalence of Russian clubs in major European tournaments. CKSA Moscow were crowned champions of the 2005 UEFA Super Cup and Zenit St. Petersburg won the 2008 UEFA Cup. Russia’s outstanding hosting of the 2018 FIFA cup was seen as both a victory for Russian soccer and Russia’s international image. Lastly, 2020 saw, for the first time in history of the UEFA Champions League, three RPL teams qualify for group play (Zenit, Lokomotiv Moscow and Krasnodar).

If financing issues and the disparity in play between the top clubs and lower tier clubs can be resolved, or at the very least mitigated, there’s no reason why the Russian Premier League cannot build on its now three decades of success and become one of the top leagues in Europe and the world.

Spartak Moscow

By Hudson Dobbs

Spartak Moscow is arguably the most successful football club in the history of Russia – a 12-time USSR champion, 10-time USSR cup winner, and 10-time Russian Football Championship winner, this football club has dominated in domestic play. In addition to their domestic success, Spartak Moscow has made its presence known all over the country, being voted as the most popular team in 59 out of 85 regions of the country.

The history of Spartak is long and complex, but the official club, as it is known today, was created in 1935. Former captain of the Soviet Union National Team, Nikolai Starostin, along with his colleague Alexander Kosarev, changed the name of the Moscow Sports Club to Spartak. The name is the Russian version of “Spartacus,” the Greek slave who led a rebellion and who was seen as a great hero by the USSR.

In the same year, Spartak played their first match, earning their first official victory as Spartak at the Trekhgornaya Manufaktura stadium. In 1937, the team was awarded the Order of Lenin for its help in the development of sports in the USSR. Spartak was achieving success without official association with any governmental department or trade union, as was seen with most of the major teams under the USSR. This sense of independence attracted people to support Spartak, resulting in it being referred to as the “people’s team.”

The early years of the USSR Football Championship (starting in 1936) proved to be successful for Spartak – resulting in several top three finishes and the creation of a significant rivalry with Dynamo. The 1941, the championship was interrupted by the Great Patriotic War, and several of Spartak’s players and coaches were either drafted or volunteered to fight. The next few years proved to be difficult for the club, and, when the championship resumed play in 1945, Spartak had clearly lost its momentum and cohesiveness – barely avoiding relegation to the lower league amid several coaching changes. It didn’t take much time to get back on track, however, as the team achieved a top 3 finish in the USSR Championship in 1948.

In the years following, Spartak, often known as the “Red and White” for their distinctive colors, continued to dominate play in the USSR and remained one of the most popular and successful clubs after the collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991.

Although they have been quite dominant in domestic competition, their international play has not yielded quite as significant results. Although they have competed in UEFA competitions, they have yet to win the UEFA Cup or the Champions League. Their UEFA club coefficient ranking is 60, which is respectable, but not as prestigious as competitors such as CSKA (49), Lokomotiv (48), and Zenit (33).

Today, Spartak participates in Russia’s youth leagues with Spartak Junior, a club run by the team’s management that has yearly soccer camps as well. Spartak’s major sponsor is Lukoil, known as one of Russia’s most independent hyrdocarbon companies. Spartak plays in Otkrytie Bank Arena in Moscow, named for another of their major sponsors. In addition, the team has also been referred to as the “champions of sponsorships” – with nearly twice the logos on their jerseys as any other Russian team. Other sponsors with jersey space currently include IFD Kapital, the Winline betting company, Trekhgornoye beer, Nissan cars, Gorenje household appliances, and several more.

They currently play in, and sit in ninth place in the Russian Premier League for the 2021-22 season.

Zenit St. Petersburg

By Hudson Dobbs

Zenit was born in 1925 in Leningrad (now St. Petersburg) through a merger of several football teams associated with the Leningrad Metal Plant (LMZ). Many of the club’s matches around this time were either intra-plant competitions or with teams formed by neighboring enterprises. In 1929, plant director Ivan Nikolaevich Penkin came to the metal plant with the intention of making the team a real competitor. In 1931 the team made its debut in the St. Petersburg Football Championship – taking third place. At this time, the team was known as “Команда ЛМЗ им.Сталина” (Team LMZ named after Stalin) or simply “Металлический завод” (Metal Plant).

The club went through several early restructurings. From 1934 to 1936, several key people joined the club, including the first head coach Pavel Butusov and the first star player Boris Ivin. Before the first USSR Championship in 1936, however, Butusov was replaced by well-renowned football expert, Pyotr Filippov. In July of the same year, the team competed in its first USSR Cup. Later in the same year, the team became known as the “Сталинец” (Stalinets) under the sponsorship of the DSO (Voluntary Sports Society) and received their official colors of blue and white from the DSO’s official colors.

In February of 1939, as a result of a major management reorganization, the Leningrad Metal Plant and its team were turned over to the jurisdiction of the People’s Commissariat of Arms. The Commissariat already had a DSO known as Zenit and thus the Stalinets were absorbed into the Zenit DSO, gaining what would be their final name.

The team didn’t find success, however, until 1978 when soccer legend Yuri Morozov was hired to take the head coaching position. Under his command, the team had its first noteworthy finishes in 1980 – its first USSR Championship medal and its first qualification for European competition – the 1981 UEFA Cup.

After the collapse of the USSR in 1991, Russian soccer was reorganized and Zenit was placed in The Russian Premier League, the new top-tier championship league. Like most organizations at this time, however, the team struggled with finances as it sought to shift from factory-affiliated to an independent organization. In the process, they lost much of their best talent and performance deteriorated.

Zenit’s first several years post-collapse were difficult. A 16th place finish in the 1992 Championship resulted in Zenit being relegated to the lower division. Three years later, the team was finally able to return to the Premier League top division. The resilience of the club was apparent, as they claimed their first Russian Cup title 1999 – only seven years after being relegated.

Following their title in 1999, Zenit has maintained a fairly consistent level of competitiveness – including a Russian Premier League Cup in 2003.

In 2005, Russian corporate giant Gazprom bought a majority stake in the club, and it began to form into a true world competitor. The natural gas company invested over $100 million in new players, coaches, and the construction of a new stadium – now known as Gazprom Arena.

The club soon after won its first UEFA Cup Final in 2008 – defeating well-renowned opponents such as Marseille and Bayern Munich along the way. As if this achievement weren’t impressive enough, the club went on to beat one of the world’s best, Manchester United, in the UEFA Super Cup just a few months later.

Since their dominant run in 2008, Zenit has had continued success domestically and abroad. They have won three Russian Premier League titles and two Russian Cups. In international play, they have yet to win another UEFA competition. However, they have had a respectable amount of success. Today, Zenit is known for their dominance in Russia – having just won the Russian Premier League for the third year in a row. They have earned sponsorships from companies such as Nike, Nissan, and Pepsi.

CSKA Moscow

By Zack Johnson

Founded in 1911, CSKA Moscow has taken various forms during its more than 100 years. The club was originally founded as an offshoot of the Amateur Society of Skiing Sports, also known as OLLS, an acronym taken from the Russian name “Общество любителей лыжного спорта.” Following the Russian Civil War, the OLLS was incorporated into the Red Army, becoming its state-sponsored, official sporting arm.

In its early years, the name of the soccer team changed from OLLS to CDKA, and eventually became CSKA, from the Russian “Центрального спортивного клуба Армии,” which translates as “Central Sport Club of the Army.” In international competitions, the team was often simply referred to as “The Red Army Team” – giving them a particularly daunting air.

CSKA built a strong reputation as a 7-time league winner and winner of the final Soviet League Cup in 1991. However, the collapse of the Soviet Union also meant a collapse and reorganization of Russian soccer as well as several years of funding crisis for the sport. The 1990s thus brought dark days for CSKA, which was without a league title until 2003. However, they have since won five more league titles and seven Russian Cups. CSKA also won the 2005 UEFA Cup, a European tournament that football fans will recognize as the precursor to the current UEFA Europa League Tournament.

Off the pitch, financing and sponsorship issues have been the subject of much speculation for CSKA (as is common for most of the major clubs of the Russian Premier League).

Since 2001, Yevgeny Giner has served as CSKA president. Giner, a well-known Ukrainian businessman, has ties to the Russian government and is a friend of Russian billionaire Roman Abramovich. The UEFA investigated Abramovich for financing CSKA Moscow after Sibneft, a company in which Abramovich had majority stake, signed a three-year sponsorship deal with CSKA. Abramovich had purchased the English football giant Chelsea the year prior, and thus was officially prohibited from holding a 51% share in CSKA or any other team, as UEFA rules “forbid anyone from owning two teams in the same competition.” Ultimately, Abramovich was cleared by UEFA of any potential conflict of interest and his firm Sibneft would continue on with their sponsorship of CSKA for the year, but left following that year.

Since then, other major multinational firms have since sponsored the club. Notable examples include Internet retail giant Wildberries, Aeroflot airlines, Hyundai motors, Fonbet betting service, and Pochta Rossii postal service. Last year Russian state-controlled bank VEB acquired a 77.63% stake in the club, converting a debt obligation into club ownership.

Today, the team’s new field is locally known as VEB Arena (but also known as CSKA Arena due to European sponsorship regulations), and the team’s board of directors is dominated by VEB executives and led by Maxim Oreshkin, Russia’s former Minister of Economic Development. This new arrangement has led some to worry about the new bureaucracy, but it should certainly give the team some potentially deep pockets and political clout.

CSKA today remains an icon of the Russian Premier League, where it is placed sixth. If one is fortunate enough to visit Moscow in the future, keep a look out for fans of the кони (horses), proudly displaying their red, white and blue trademarked CSKA scarves.

CSKA Football Club has had a long and fascinating history, and despite funding issues and a slow start in the post-soviet decade, the club remains, and will continue to be, a staple of Russian sporting culture.

Lokomotiv Moscow

By Lee Sullivan

Lokomotiv is a top Russian soccer team based in Moscow. Founded in July 1922, it is one of Russia’s oldest soccer teams. Originally, the team was called Kazanka because all its players were workers on the Moscow-Kazan Railway. The team grew to include players from several railways in Moscow, and from 1923 to 1930 changed its name to a more general Club of the October Revolution. However, it then returned to its original name, Kazanka, for six years before settling on the name Lokomotiv in 1936. This was an apt name choice because during Soviet times, the team was owned by the Soviet Ministry of Transportation.

In its early history, Lokomotiv competed in several domestic competitions against other Soviet teams, including winning the first Soviet Cup Final against Dinamo Tbilisi in 1936. This marked the beginning of a successful streak that continued until after World War II when the team was dropped from the Soviet Top League. However, in 1951 Lokomotiv was reinstated to that league, meaning that their misfortune was short-lived.

In the period of increased openness during Khrushchev’s 1950s Thaw, Lokomotiv established a notable international presence as they were allowed to compete with foreign opponents in Europe, Asia, Africa, and even North America. Up until that point, competition with foreign teams had been extremely rare for soccer teams.

During the 50s, many great Soviet soccer players joined the team and, in 1957, Lokomotiv won its second Soviet Cup. However, many players then were recruited away from the team, leaving it largely unstable until the 1980s.

Following the collapse of the Soviet Union, the newly independent Russian Federation had an economy in shambles. Soccer was not a top priority for state funding, so many teams experienced funding issues as they attempted to transition to independent entities. Of the top Russian soccer teams, namely CSKA, Spartak, Torpedo, and Dinamo, Lokomotive was considered to be weakest among them. At the time, the absence of competition from teams in the former Soviet republics allowed Lokomotiv to rise back to the top of the new Russia-only field.

By the end of the 1990s, Lokomotiv was gaining a sizeable fan base. The team was performing well domestically and had a renewed international presence. They participated in a European soccer competition for the winners of domestic soccer cups twice and reached the semi-finals both times. All this led to the construction of the Lokomotiv Stadium in Moscow in 2002. The new stadium was an upgrade from its previous stadium and funded by the Russian Transport Ministry. Later in 2017, Lokomotiv made a deal with Russian Railways that renamed the stadium to RZD Arena.

In 2002, and again in 2004, Lokomotiv won first place in the Russian Premier League championship. A few years later the long-time head coach left the team, prompting a long struggle to find a comparable replacement. This struggle strongly affected the team until 2016, causing mediocre performance. However, eventually the team rose back to win the Russian Cup in 2016, its third Russian Premier League in 2017, another Russian Cup in 2018, and the Supercup of Russia in 2019.

Lokomotiv currently has domestic and international sponsors including: Adidas, Russian Railways, 1XBet, Sogaz, Bosco Di Ciliegi, Pepsico, and Bud. The team also currently has a youth group, known as Lokomotiv Moscow Youth.

FC Rubin Kazan

By Zack Johnson

FC Rubin hails from Kazan, the capital of the Russian Republic of Tatarstan. A relative newcomer to the top flight of Russian soccer, Rubin payed their inaugural Premier League season in 2003.

Founded in 1958, FC Rubin Kazan was originally known as “Iskra,” which means “Spark” in Russian and was the once a catch word in Soviet patriotic speech as Lenin had once called for the “spark” to start the revolution. The current name, “Rubin,” translates to “Ruby,” and was first adopted in 1964. This name was taken from an eponymous radar system installed on aircraft produced at the prestigious Kazan Aviation Plant. In addition to recalling finding a sticking a target with precision, it fits well with the bright red jerseys, which would have also been quite patriotic under the USSR, hailing the national color and flag.

Despite the patriotism and metaphor, the team managed to move only from the lower level to the top level of the USSR’s second-tier league during its Soviet years. Then, the collapse of the USSR and the Soviet League left FC Rubin mired in structural and financial issues throughout most of the 1990s.

FC Rubin survived that decade only through the efforts of a consortium of commercial structures that supported them. In 1996, the city administration, under Mayor Kamil Iskhakov, also became involved. This led to increased funding and better organization that would reinvigorate the club, setting it on a path to eventually break into the Russian Premier League’s top division in 2003.

In that first season, quite astonishingly, FC Rubin finished third in the league, even beating out heavyweights like Lokomotiv and Spartak. What’s more, only five years after that, Rubin was crowned back to back league champions in 2008 and 2009.

In the 2012-13 Europa League campaign, Kazan beat out Italian giant Inter Milan for top place in its group. It eventually lost only in the quarterfinals 4-5 to English super club Chelsea by one goal on aggregate.

All of this has helped Rubin attract still more top global talent. The signing of the remarkable forward Obafemi Martins, from Nigeria, helped the team win the 2011-12 Russian Cup. In more recent years, the signing of Alex Song, the Cameroonian of both Arsenal and Barcelona note, further illustrates the club’s ability to compete for top talent.

All of this has been achieved with relatively modest sponsors, especially in comparison to Moscow and St. Petersburg teams, which often sport the logos of some of the world’s largest corportations on thier jerseys. Rubin’s sponsors are mostly local companies and include two petrochemical companies, Volzhanka mineral water, Fonbet betting service, and Kalina, a medical technology company.

In 2013, FC Rubin received a new home stadium, in 2013. It was built as part as major infrastructure push in Kazan as it prepared for the 2013 Summer Universiade, which is a sort of collegiate Olympics that draws athletes from most countries. Ak Bars shares its name with its general sponsor, Ak Bars Bank, and a Tatar mythical creature, the Ak Bars, which is a white, winged leopard that represents honor and strength. The arena is situated just northeast of the city center on the banks of the Kazanka River and seats an impressive 42,000 fans. When Kazan was chosen as one of the Russian cities to host the 2018 FIFA World Cup, those games were also played at Ak Bars.

Kazan is today an economically successful city with a strong streak of independence and pride. This rise has helped create and is partially reflected in the success of FC Rubin.

Dynamo Moscow

By Zack Johnson

Dynamo Moscow is one of the oldest and most storied clubs in Russian soccer. Founded in 1923, the blue and white of Dynamo are one of the “Original 5” of the Moscow-based clubs, which also include CSKA, Lokomotiv, Torpedo, and Spartak.

Like other Soviet era sport clubs CSKA or Lokomotiv, Dynamo traces its genesis back to the state itself. Dynamo was originally founded as part of the Soviet Security Services Sporting Club. It’s founding patron was none other than the notorious founder and first head of the Soviet Secret Police, Feliks Dzerzhinsky.

The rallying cry of the Dynamo Football Club was and remains “Strength in Motion,” an axiom attributed to the great Russian writer Maxim Gorky. The club certainly showed its strength during the Soviet Period, being crowned champion eleven times, with their final title coming in 1976.

Instrumental in this success was legendary Soviet goalkeeper Lev Yashin. In 1963, Yashin became the first and only Soviet player to win football’s most prestigious individual award, the French Ballon d’Or. Yashin’s fame has long outlived him. Dynamo’s new arena, opened in 2018 and sitting just northwest of the city center, is officially known as Dynamo Lev Yashin Stadium, in honor of the famous keeper. There was also a 2019 biographical film made for him – marketed in English as The Black Spider, a nickname given to him for how well he guarded his “web.”

Despite its Soviet-era success, the post-1991 transition to the Russian Top Division and later the Russian Premier League, proved dark times for of the historic club. Outside of a Russian Cup win during the 1994/5 season and a third-place finish in the 2008 Russian Championship, the blue and white have been unable to replicate much of their Soviet League glory.

In 2014 the club, following a fourth-place league finish and thus qualification for the Europa League, appeared destined for a new era of success. Yet, any dreams of the dawn of a new era were quickly dashed. After a lengthy investigation, UEFA ruled Dynamo had breached its break-even requirements within the Financial Fair Play Rules. UEFA officials questioned whether the fair value of the sponsorship deal between lead sponsor and majority shareholder VTB Bank and the club had been properly assessed when calculating Dynamo’s relevant income. Ultimately, it was proven that the club had greatly exceeded UEFA’s maximum allowed deviation between relevant income and relevant expenses. As a result of the ruling, the club was banned from Europa League play for one year and forced to sell various players to balance its dismal budget situation.

Unfortunately, the UEFA ruling would prove only a false bottom for the team and its supporters. Two years later the club was dealt another serious blow. For the first time in its 93-year history, Dynamo was regulated from the top division play with a season ending loss against Zenit St. Petersburg.

Despite Dynamo’s struggles on and off the pitch, there remains reasons for optimism. Dynamo successfully returned in 2017 to the Russian Premier League after only one season in the second division.

They also continue to leverage their historical fame into big-name sponsorships such as from Chevrolet, Internet retail giant Wildberries, Rossiya Airlines, 1xStavka betting service, and others.

They are also actively and successfully developing their Lev Yashin Academy, a prestigious training facility financed with an endowment of some $67 million from VTB Bank. As of 2020, 13 graduates of the academy were on the Dynamo roster. In 2021, the team recorded seven wins and only four losses, indicating that today’s Dynamo is focusing their training and finances on the growth and success of the team.

You Might Also Like

Kyrgyz Soccer: An Introductory Guide

The history of soccer in Kyrgyzstan goes back to 1921, with an oft-cited first match taking place in Bishek, Kyrgyzstan’s capital city, against a team from Kazakhstan. The Kazakh team won, but not before the sport of soccer staked a permanent claim on the Kyrgyz national consciousness— the game’s been culturally significant ever since. However, […]

Georgian Soccer: An Introductory Guide

The history of soccer in Georgia goes back to the late 1800s, when it was brought to country by English sailors shortly after the sport was invented. Although Georgia was an early adopter of the sport, its development has been arguably held back by colonialism. Georgia was largely a backwater for Soviet soccer and the […]

Watching FC Kairat Almaty at Almaty Central Stadium

For traveling soccer fans, attending a live game is a wonderful way to experience a unique part of local culture. Despite being a truly global sport, soccer has a unique culture everywhere it is played. Whether it be the chants or the food at the concessions, there is always something to learn about the local […]

Polish Soccer: An Introductory Guide

The history of soccer in Poland begins when the county didn’t technically exist – having been partitioned by larger powers. Like the rest of the country, Polish soccer eventually united after Poland was reassembled after WWI. Soccer was again set back in WWII when the Nazis banned the Poles from organizing games, fearing that fed […]

Kyrgyz Soccer: An Introductory Guide

The history of soccer in Kyrgyzstan goes back to 1921, with an oft-cited first match taking place in Bishek, Kyrgyzstan’s capital city, against a team from Kazakhstan. The Kazakh team won, but not before the sport of soccer staked a permanent claim on the Kyrgyz national consciousness— the game’s been culturally significant ever since. However, […]