Aleksei Balabanov is one of Russia’s best known directors of the 1990s and his movies are known for capturing the essence of those turbulent years. Below is brief biography for him and several synopsis and reviews of his work, with links to watch them in the original Russian on YouTube.

Balabanov’s Education and Early Work

By Matthew Jensen

Aleksei Oktyabrinovich Balabanov was born in the town of Sverdlovsk (now Yekaterinburg) on 25 February 1959. He studied at the Gorky Pedagogical Institute and graduated with a degree in foreign languages in 1981. After completing his university studies, Aleksei joined the Russian army as an interpreter and served in Afghanistan with a military aviation unit for two years. This experience doubtless had a tremendous impact on his creative vision, as evidenced by the ex-soldier turned moral avenger protagonist of Brother and Brother 2 as well as the disturbingly dark subject matter of Cargo 200.

After being discharged from military service in 1983, Aleksei returned to his hometown of Sverdlovsk. His father, Oktyabrin Sergeevich Balabanov, was editor-in-chief of the scientific films department of Sverdlovsk Film Studio and helped Aleksei get a job there as an assistant director. At the time, Sverdlovsk was a thriving hub of the 1980s underground Soviet rock movement. In particular, Balabanov became personally acquainted with the two founding members of the famous Soviet rock band Nautilus Pompilius, Vyacheslav Butusov and Dimitry Umetsky, both former students of the Sverdlovsk Architectural Institute. Their music frequently appears in Balabanov’s later films, the most notable being Brother, where the protagonist falls in love with their music after listening to one of their albums on his Walkman.

Balabanov spent four years working as an assistant director before he made his first film, a short thesis film developed from a script that he wrote overnight. The film was shot entirely in a local restaurant using patrons and friends from Nautilus Pompilius. Later, he attended the postgraduate Higher Courses for Scriptwriters and Film Directors program offered by the Gerasimov Institute for Cinematography (VGIK), and in 1991, he directed his first feature film: Happy Days.

Based off of several works by Irish writer Samuel Beckett, Happy Days proved to be а critical success on the film festival circuit, including for Cannes, and won three awards. His next film, The Castle, an adaptation of Franz Kafka’s unfinished novel of the same name, was likewise well-received by Russian critics and paved the way for his future success. Together with fellow director and producer Sergey Selyanov, Balabanov founded the STV film company which was used to fund many of his future films.

Balabanov’s Later Life and Works

By Mikhail Shipilov

Aleksei Balabanov said that he made films not only for himself and for the Russian people, but also, like any great artist, for the entire world. While his importance to Russian culture is difficult to overestimate, he was also one of the important figures of international cinema.

The films Brother and Brother 2 are both included in the top 20 most popular Russian films on IMDB. Two more of his films, Cargo 200 and Blind Man’s Bluff, are 32nd and 41st on the ratings list respectively. If IMDB ratings are anything to go by, his films are well liked abroad; the previously mentioned films all have an average rating of between 7 and 8 out of ten on the site.

Regardless of the popularity of Balabanov’s films in Russia and abroad, they are often mistaken for what they are not. For example, judging from the opinions of viewers, Russian audiences valued Brother and Brother 2 as an allegedly realistic and truthful story of an incorruptible man that many still take as an example to be followed. Foreign viewers, however, often speak about Balabanov’s duology as entertaining but artless action films from the exotic Russia of the 1990s. Scholars of his work regard the Brother movies as very different, yet equally romantic depictions of the tragic hero, the image of which sprang from the collective unconscious of that same 1990s Russia.

Another of Balabanov’s famous films, Cargo 200, caused a wave of scandals in Russia: the director was called a scumbag and a pervert after its release, and the film itself was derided as a disgrace and a mistake. Cargo 200 usually appears in English-language resources on lists of films whose primary or only purpose is to disgust viewers. When Balabanov was given the chance to speak about it (which rarely happened), he said that Cargo 200, like all of his films, was about love. Only when you understand this contradictory work do you realize there is no hint of provocation in the director’s words.

All of these disagreements confirm that Aleksei Balabanov’s film language remains not only relevant in Russia and abroad, but also not fully understood.

Balabanov’s Death and Continued Significance

By Mikhail Shipilov

Throughout his artistic career, Balabanov was interested in the topic of intercultural relations. In his own films, he repeatedly showed how strongly people from different cultures can differ from each other and how often they cannot – and, more importantly, do not want to – understand each other. Brother 2, for example, is completely dedicated to a journey to a mythological version of America, invented in the USSR for lack of the real thing; War tells of the tragic lack of understanding between nations and cultures; one of Balabanov’s few failed projects is a film about an American who, by chance, winds up in a settlement of the Tofalars, an indigenous group native to Siberia.

Ironically, Balabanov has been accused of xenophobia for scenes that are frequently mistaken for nationalist propaganda but that actually ridicule and denounce ethnic strife. In fact, Balabanov was an artist who was not afraid to raise controversial topics and believed in the sensitivity of his viewers. He strongly felt the fundamental disharmony between peoples, cultures, and nations but at the same time knew that it was inevitable. From this natural inconsistency were born such scenes, some emphatically humorous and others disturbingly realistic.

In 2013, after several decades of filmmaking, Balabanov tragically suffered a heart attack and passed away at the age of just 54. He is survived by his second wife Nadezhda Vasilyeva and his two sons Pyotr and Fyodor.

Today, Balabanov’s films are particularly relevant as mutual understanding between people of different cultures is now the most important currency in a globalized world.

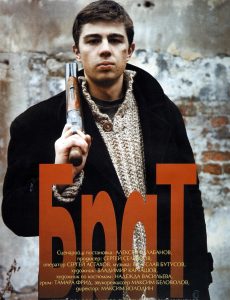

Brother (Брат): Synopsis and Full Film

By Julie Hersh

Brother (Брат) is a cult Russian drama/action film from 1997 directed by Aleksei Balabanov and staring Sergey Bodrov Jr..

The film won awards from a number of film festivals, and it was nominated for a Nika for best film and won the Kinotavr (a film festival) award for Best Male Actor, for Sergey Bodrov Jr., who played Danila. Though it didn’t win any of the more major prizes, it is now regarded as one of the more impressive films to come out of Russia in recent years. It has achieved cult status, with very high audience scores and a spot on KinoPoisk’s top 250 films. (Very few of those are Russian films, which highlights the achievement.) It has very good (but not universally so) ratings from critics, but it is a definite fan favorite.

Watch the full film on YouTube by clicking here.

Brother 2 (Брат 2): Synopsis and Full Film

By Julie Hersh

Brother 2 (Брат 2) is the 2000 sequel to the cult favorite Brother (Брат), released in 1997.

The film starts out with Danila Bagrov, the hero of both films, taking part in a television program about the heroes of the Chechen War, which he had fought in several years earlier. He gets involved soon after in criminal activities once again, as a friend of his, a security guard for a bank, is gunned down and he wants revenge. Simultaneously, his brother, Viktor, needs his help, in a turn of events that echoes but is the opposite of those of the first film. Viktor and Danila team up in this new endeavor and they find themselves traveling to the United States and entering the criminal underworld of Chicago, where the Ukrainian mafia holds sway.

Brother 2, like the original, became a significant cultural phenomenon. While retaining Danila Bagrov as its central figure, the sequel shifts the setting from post-Soviet urban stagnation to a more expansive, global landscape, moving between Moscow and the United States, and in doing so mirrors a society increasingly aware of its place in a wider, often hostile world. America is portrayed as not a land where the streets are paved with gold, as many Soviets behind the iron curtain dreamed it to be, but as a place with its own crime and poverty to be dealt with.

Danila remains a man of simple moral certainties, guided by a strong sense of loyalty and justice, but in Brother 2 his worldview becomes more assertive and national in tone, in particular articulating a belief that an individual’s moral strength can always triumph over financial or institutional power. One of the movie’s most quoted lines is when Danila asks “В чём сила, брат?” (“Where does power lie, Brother?”) The answer he gives to his own question is “У кого правда, тот и сильнее.” (He who has truth is stronger.)

Stylistically, the film is more polished and dynamic than its predecessor, yet it preserves Balabanov’s directness and lack of sentimentality, presenting violence and confrontation as almost normal parts of everyday life. As in the original, music again played a major role in the popularity of the film and its resonance with audiences. The soundtrack dominated by many bands that came to dominate the post-Soviet rock scene such as Smyslovye Gallyutsinatsii, Splean, and Zemfira.

Ultimately, Brother 2 is often read as a film about post-1990s disillusionment and emerging self-assertion: a story in which the solitary hero no longer merely survives chaos, but actively confronts a world perceived as unjust, embodying the tensions, aspirations, and unresolved contradictions of Russia entering the 2000s.

The film did very well, with fans of the first one perfectly satisfied with the sequel. It got good audience ratings and, like the original, appears on KinoPoisk’s list of top films (according to audience vote). It was nominated for only one award, for the Gold Rose at the Kinotavr film festival. Film critics’ opinions seem less important when dealing with cult films of this type, though one, Andrey Orletskiy, wrote that “the stupidity [of the film] is terrible, but somehow I liked it.”

A third film was planned, but Sergey Bodrov Jr., the actor who portrayed Danila, tragically died in a landslide while on set for another film. Director Aleksei Balabanov put the series to rest with the actor.

There is, however, video game based on it, Brother 2: Back to America (Брат 2: Обратно в Америку; see a video play through here)—it is a first-person shooter and was one of the first fully Russian computer games. It did not receive good reviews from the gaming community. There is also a documentary about the film called Brother 2: Film About the Film (Брат 2: Фильм о фильме). Interestingly, a film called “Brother 3” was eventually made an released, although it is in no way connected to the series.