Late-Soviet Siberia fell in love with punk. While rock bands like Kino and Alisa were making waves in Leningrad, the major industrial and scientific centers of Central Russia produced an underground punk genre that grasped audiences in the USSR and post-soviet diaspora.

The cities of Tyumen, Omsk, and Novosibirsk were the centers of this movement. These cities had large universities and institutes with significant student populations. The scientific institutes in Novosibirsk and refining industries of Tyumen and Omsk attracted foreigners that brought new technology and trade. These foreigners occasionally brought in new music as well.

The Sex Pistols were particularly popular among Siberian students in these cities during the early to mid-1980s. As bootleg tapes circulated, some fans found that the band’s punk style was vibrant and easy enough to imitate. Local punk groups began to form, often even before the members knew how to play their instruments.

At first, the groups were mostly copying western bands. However, after some time, Siberian punk became its own unique style.

The DIY Essence of Siberian Punk

Siberian punk was an intellectual movement that revolved around protest and a rejection of the norms of Soviet society. The movement’s outward expression and musical style were not nearly as important as its symbolism. For example, Siberian punks of the 1980s and 90s didn’t have a concrete fashion like their British and American counterparts. They were instead interested in the “avant garde essence” of punk, focusing on the message and emotion behind their performances and music.

The music itself was often simple and aggressive, and the recordings styles often emphasized this in their rawness. Most of the genre’s recordings were actually recordings of recordings of recordings, meaning that widely available copies were often poorer quality. In general, fans weren’t concerned about the bootlegedness of these recordings and even welcomed it. The haphazard, grittier recordings showed that the art was sincere and their widespread distribution exemplified fans’ instant connection with the music.

Party-enforced censorship was less common in Siberia. Punk venues had a DIY, makeshift quality and could close just as quickly as they were targeted by state authorities, simply popping up in new underground location. Dorms, apartments, and, perhaps most symbolically, the rapidly growing number of abandoned industrial spaces were preferred venues for the growing number of punk groups.

As bands began producing their own music, they worked uniquely Siberian themes into their lyrics that resonated with local audiences: housing crisises, bitter Siberian winters, the local torment of rising alcoholism in aging industrial centers, and generational trauma of the Afghan War. Siberian punks’ opposition was not only political but also existential, pushing back against both Soviet power and the newer, more democratic ideologies of the Gorbachev era.

One very early example of this was the Tyumen group, Инструкция по выживанию (Survival Instruction). Their song, “Афганский синдром” (Afghan Syndrome), critiqued Soviet military involvement in the Afghan War with shocking openness and graphic imagery, decrying what was seen as state-sponsored violence against “unborn children” and “soldiers.”

Above: “Afgahn Syndrom” by Survival Instruction, 1990

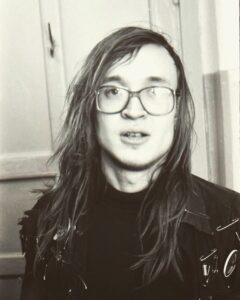

Egor Letov and DIY Siberian Punk Studios

While Siberian punk bands were able to include stark criticism of the state in their music, it is not to say that censorship never happened. Egor Letov’s band, Гражданская оборона (Civil Defense), also included state and societal criticism in its lyrics. Based in Novosibirsk, Letov was an active organizer in the Siberian punk community, drawing the attention of state censorship authorities. Letov was forcibly committed to a state psychiatric institution, a common silencing tactic. Other outspoken punks were often drafted into the army in attempts to distance them from the growing movement.

While taxing on the individual to say the least, these punishments didn’t hamper punk’s development in Siberia. Letov, for instance, returned to music and organizing immediately after his release. As censorship policies loosened during Glasnost, punks like Egor Letov formed their own labels. Letov’s record label, known as ГрОб (GrOb – a play on words, being both an abbreviation of Grazhdanskaya Oborona and the Russian word for “coffin”), recorded anyone who even remotely peaked his interest. New punk groups from throughout Siberia flocked to festivals in Tyumen, Omsk, and Novosibirsk with the hopes of meeting and recording with ГрОб.

The authorities found recording and music distribution extremely hard to control because, as was the case with DYI performance venues, Siberian punk operated with the idea that any space could be a recording space. Letov recorded anywhere he could: in friend’s apartments, dorm rooms, or apartment building basements.

Other punk labels operated in a similar fashion, producing a wide body of music in a highly efficient and resilient network. Producers and their clients sent finalized recordings to other parts of the USSR and beyond, where they were copied and redistributed many times over. Listener-to-listener distribution broadened not only Siberian punk’s audience but also the breadth of its social influence.

Letov became an outspoken commentator on Perestroika, the fall of the USSR, and later issues as well. Songs like “Всё идёт по плану” clearly show his discontent with Perestroika and the government’s neglect of collective trauma during a massive economic shift. The song’s refrain, “всё идёт по плану” (everything is going to plan), points to the Russian Federation’s willingness to go forward with its economic agenda regardless of the suffering of its people.

Above: “Everything’s Going According to Plan” by Grazhdanskya Oborona, 1988

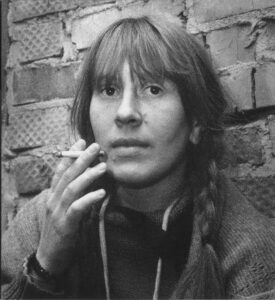

The Rise of Yanka Dyagleva and the Last Efforts to Control Punk

Yanka Dyagleva rose to fame in 1988, after her debut performance at the Tyumen Festival of Alternative and Left-Radical Music. She traveled with Egor Letov and Гражданская оборона on their tours, but her lyrical and musical style differed greatly from that of her contemporaries.

Yanka was one of the only headlining women in the punk community and added her own composed and artfully honed rage to the fire of the musical movement. She used poetic lyricism alongside linguistic nuances found in traditional folklore and Communist Party rhetoric to sharpen the cultural criticism in her songs. Her new style proved popular with audiences.

Her songs also carried the weight of her personal struggle with depression, mixing it with social criticism to produce tracks like “Гори, гори ясно” (Burn, Burn Brightly), “На чёрный день” (On a Black Day), and “По трамвайным рельсам” (Along the Trolly Tracks).

By the time of Yanka’s debut, Komsomol officials offered opportunities to tour around the country with a state entourage. It was an attempt to contain what, by that time, could not be controlled. The efforts were largely unsuccessful as the creative character and rebellious ideology of Siberian punk didn’t align with the repetitive nature of state-sponsored touring, which demanded rigidly defined setlists and routines. As the Siberian punk fanbase grew, the need for state-supported tours diminished. Bands developed a network of ad-hoc venues across the USSR where they could play, drawing crowds wherever they could perform.

Yanka and later Soviet Siberian punks gained popularity as truly independent stars, supported by their fans rather than money and the Party. They were able to create on their own terms and avoid micromanagement from Party bodies like the Komsomol.

Yanka’s death in 1991, just three years after her debut, was a blow to the Siberian punk scene. Following a severe depressive episode, Yanka was found in a river near her family’s dacha. Many cite her death as a symbolic end to the golden age of Siberian punk.

Above: “Burn, Burn Brightly” by Yanka Dyagleva, 1989

Perestroika Punk and the Fall of the USSR

Despite Party efforts at censorship, Siberian punk proved resilient, relying on personal connections and its DIY spirit. By the fall of the USSR, it was an established part of youth culture in Siberia. The music reflected and influenced younger generations’ views on the mounting problems they faced in post-soviet world. Punks also remained largely critical of the authorities after Yeltsin came to power in 1991. Bands continued touring and their lyrics shifted to criticize the Russian Federation’s government and its reforms.

The Siberian punk movement had a large influence on other groups across Russia and other former Soviet republics, provided an alternative to mass Soviet culture and resisted Party censorship. Although its direct effect on the disintegration was likely minimal, the movement united younger generations during a time of societal disorganization and economic turmoil.

Although many of its early practitioners have passed away, punk is still alive in Siberia. ГрОб is still an active record label, one of several now specializing in punk. Tyumen, Novosibirsk, and Omsk also still have punk clubs. The true essence of “Siberian punk” has now, many argue, been absorbed into the wider punk movement. Contemporary punk bands continue to form in Siberia, with the new punk hub of Yakutsk producing bands like Юность севера (Youth of the North) and имя твоей бывшей (The Name of Your Ex).

The influence of Siberian punk is also visible today in scenes like the Moscow musical underground, where DIY music production, recording, and the establishment performance venues help avoid pushback from state authorities. Among the most notable groups, Pussy Riot uses organizational tactics similar to those of Siberian punks, with early albums like Убей сексистов (Kill the Sexists) recorded in abandoned warehouses and group meetings held in a wide network of apartments across the city.

Through playful lyricism, the introduction of Western music styles, and a general sense of self-determination among musicians, Siberian punk changed listeners perceptions of was acceptable to both the Party and society as a whole.